Autumn 2013

Cold war modern machine music

Sounding the Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957-1984

Calvert 22, Calvert Avenue, London E2 7JP<br>26 June-25 August 2013

Music humanises technology: from the thump of a hunter’s bone to the whine of a radiowave in a theremin. A musician will soon draw the flavours of the tool’s main purpose into song or dance, the musical sounds of flirting, mourning, fight or flight or community.

And after the Second World War, we had a lot of new technology to play with: computers and cybernetics, magnetic tape, the transistor …

‘Sounding the Body Electric’, first shown in Łódź in Poland, is a compact, engaging exhibition, documenting the graphic scores, conceptual ‘happenings’, musique concrète, tape collage and open-form spatial installations of a small, scattered Eastern European scene.

Dóra Maurer, András Klausz and Zoltan Jéney, frames from Kalah, 1980, a film short based on the Arab game of that name.

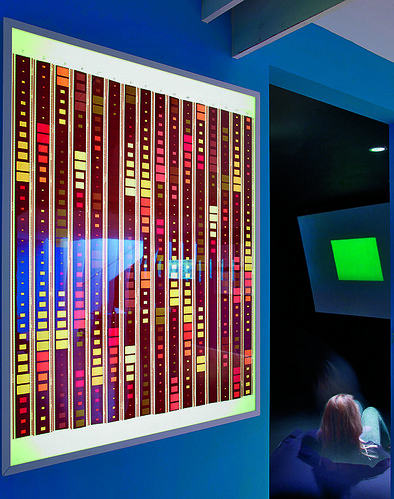

Top: Milan Knížák, Destroyed Music, 1960s-80s.

The artists behind them were based in state-funded electronic studios and research labs in Warsaw, Moscow, Brno, Budapest, Belgrade and faraway Kazan in Tatarstan. Despite certain links and apparent similarities, such work is not yet adequately cross-filed against the canonic Western understanding of postwar experimental music: this show makes an important first step towards enlarging that understanding.

Every technique on show has a Western relative, but the context for art – as curators David Crowley and Daniel Muzyczuk note – was different in Eastern Europe. For those who took the Communist bloc to be a vast social experiment in the freeing of all humanity to be itself, ‘experimental music’ – American composer John Cage’s term – would take on a far more ambiguous tone.

And so would the word ‘humanise’. At one extreme, there’s humanism as existential resistance against the soullessness of a bureaucratic state; at the other, the quasi-official hope that technology, neutral and even objective in its working, would amplify the better being and undistorted capability of the ordinary worker, liberating art and music not only from the subjectivities of bourgeois culture, but also from the capacity for human beastliness revealed across Europe during wartime and the ensuing Stalin years.

Crowley and Muzyczuk sequence the show in a way that indicates the evolution of Communist optimism towards an art of sly, subterranean resistance as the Eastern bloc lost faith in itself. The exhibits demonstrate the existence of both limits of this continuum – though perhaps less as changing mood than as simultaneous contradictory presence.

The pivotal piece in the exhibition is Just Transistor Radios, by Szábolcs Esztényi and Krysztof Wodiczko: twelve performers manipulate hand-held transistor radios, punching buttons and turning knobs as dictated by a purpose-designed graphic score. By 1968, the year of the Prague Spring, the Eastern avant-garde was familiar with Cage’s thinking, and thus presumably his Imaginary Landscape No.4, for twelve radios and 24 performers. But where Cage was coaxing the listener into hearing again the rustle of the world, the noises we’re taught to screen out of conventional music, these Polish performers placed cotton wool in their ears. Just Transistor Radios was about never being able just to listen: Western airwaves were open to all, especially on these portable, Western-style consumer appliances, but the Eastern bloc states were notoriously quick to jam such broadcasts as a tool of political punishment and control.

There is more to say about the way these opaque and never entirely playful works addressed this semi-silence. Armed with more background than the show has space to fill in – the catalogue supplies some and suggests more – you could expand on Milan Knížák’s prescient Destroyed Music project, collage sculptures and recorded cut-ups of vinyl discs constructed between 1963 and the 1980s. Or you could gaze at Bogusław Schaeffer’s extraordinarily detailed graphic score PR – I VIII, and decide for yourself how to play it.

In far Kazan, at the Aviation Engineering Research Centre, the Prometheus Institute had been set up to explore the synaesthetic theories of the pre-Soviet Russian composer Scriabin, who believed that notes and colour were mystically interlinked. In a 1965 Soviet newsreel, we see technicians designing a light-keyboard, and busy clever fingers playing it, but the show itself doesn’t survive the appalling repro quality of the little film. We can imagine one kind of clue in newsreader’s jaunty tone; quite another in the impassioned neuroses of this once-radical, now sidelined music. There’s an enormous amount to explore here, and the research has only just begun.

Mark Sinker, writer, editor, London

First published in Eye no. 86 vol. 22 2013

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 86 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.