Autumn 1994

Could this be the death of the dot?

Scanning: FM screening

How can you make a picture look its best on the printed page? In recent years the printers’ answer has been to increase the screen ruling applied to the scanned image: 200 dpi became standard in high-quality sheet-fed colour, work, and some printers are regularly printing at 300 dpi and higher. In conventional screen generation, the image is produced by dots of varying sizes in each of the four process colours in a fixed relationship to one another. Altering the relative size of the dots alters the colour. The higher the screen ruling, the larger the number of fixed dots in an area. This conventional screening is known as AM (Amplitude Moderated) screening.

But now the major repro system manufacturers are marketing under their various trade names an alternative screening technique: FM (Frequency Modulated) screening, also known as stochastic screening (from the Greek meaning random). In FM screening all the dots are the same size and are scattered apparently randomly within the image area: it is not the size of the dot that alters, but the number of dots reproduced and the space between them in each of the process colours that makes up the colour area.

The FM screen dots are individually much smaller than their equivalent in conventional screening, and because they do not have the rigid placement of a conventional screen pattern they are much less obvious on the printed sheet. This is especially true of areas of relatively constant colour in images, where the dot patterns (the rosette) caused by the four process dots in fixed relationship in conventional screening are usually most noticeable. In addition, because FM dots are randomly placed, the kind of moiré patterns that emerge when the screen angles in a conventional screened job clash with strong lines or patterns in the original are eliminated.

So will everything be FM screened in a few years? David Stone, commercial manager of Oakley Press in Bristol, is firmly convinced of the system’s advantages. Always advocates of high screen rulings, Oakley has produced all its work using Linotype-Hell’s Diamond Screening system since the beginning of 1994. ‘We were astonished by the early tests,’ says Stone. ‘Photographs are virtually continuous tone, tints don’t have that uniform pattern of conventional tint-layering and vignettes have smooth edges. For the printer, it is faster to imageset than to do high-screen ruling work and because the dots don’t have a rigid pattern, there are fewer fit problems on press. We print a lot of annual reports and with conventional screening there was always a member of the board of directors in the group photograph whose striped shirt caused moiré problems.’ Oakley has one of the most advanced printing factories in Europe: new presses have the capacity to print waterless litho, and Stone says the combination of the two processes gives rich colour and fine detail, even on recycled stocks.

In the United States, Callaway Editions produces some of the finest photography books in the world using Afga’s CristalRaster FM screening software. Native Nations, a book of photographs of the Indian peoples of North America by Edward S. Curtis, is a stunning exercise in quadratone separation and printing, using varying shades of black, grey and sepia on uncoated paper. Here the grain in the images is matched by the slight graininess of the FM process (‘Our new software can eliminate the grain,’ editorial director Nicholas Callaway points out).

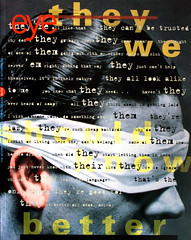

Callaway Editions produces separations in-house using techniques developed by reproduction expert Richard Benson. ‘It’s not just about a software program,’ says Nicholas Callaway of their desire to keep control over origination, ‘It’s what you do with it. It’s just a tool, albeit a miraculous tool and a tool that will do things that other tools won't.’ Cyclops, a quadratone book (two blacks, two greys and a varnish) of photographs by Albert Watson, designed by David Carson, is published in October, and Seduction, a book of photographs by Irving Penn, is in preparation. For this Callaway and Benson are working with separations of nine colours, creating intense colours built up layer by layer, a process only possible because FM techniques do not cause moiré problems. ‘They’re like little transparencies on the page,’ says Callaway. ‘The secret is in the film – we have fine printers and fine presses but printing today is about the execution of what is latent in the film.’

There are some technical hurdles to general acceptance of these fine-dot processes: Mike Boyce, technical manager at British printer Balding + Manshell, says, ‘I’ve seen some very good results, but the quality of plate-making is critical as effectively everything is a highlight dot.’ And aesthetically the look of an FM screened picture is different: sometimes the screen pattern inherent in conventional work gives a poor photographic image a sharpness and contrast that paradoxically improves its printed appearance. But there is little doubt that for high-quality originals and images with heavy patterns that might cause moiré, FM screening is a real advance.

However, the first step to making pictures look good remains, as John Bodkin of London-based Dawkins Colour says, ‘in the scanner operator’s analysis of the image when it is digitised. If a picture is badly scanned, if the contrast and balance between the colours is poor, it doesn’t matter how many or what kind of dots it is broken into afterwards.’

Simon Esterson, Graphic designer, London

First published in Eye no. 14 vol. 4 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.