Spring 2013

Guerrilla warfare, semiotic style

Autonomy: The Cover Designs of Anarchy, 1961-1970

Edited by Daniel Poyner, with essays by Richard Hollis and Raphael Samuel<br>Hyphen Press, £25<br>

The political philosophy of anarchism has attracted some extraordinary and perhaps unlikely British adherents. They included Alex Comfort (1920-2000), an expert on the science of ageing and author of the bestselling The Joy of Sex; the poet and critic Herbert Read (1893-1968), who wrote incisively about modern art; and Colin Ward (1924-2010), an architect whose ideas about the importance of self-organisation ledhim to write about many everyday things, including children’s play and garden allotments. Far removed from the cartoon cliché of the nineteenth-century-style bomb-wielding terrorist, or from the King’s Road punk, these anarchist intellectuals were cerebral figures who used their skill with words to argue for what Comfort called the ‘maximisation of individual responsibility and the reduction of concentrated power – regal, dictatorial, parliamentary: the institutions which go loosely by the name of “government” – to a vanishing minimum’. They may have rallied against the oppressive reach of the state and the ‘inflation’ of professionalism, but ‘the Establishment’ was keen to benefit from their skills: Comfort was an academic at University College London; Read was knighted in 1953; and Ward was to spend the 1970s as an education officer with the Town and Country Planning Association.

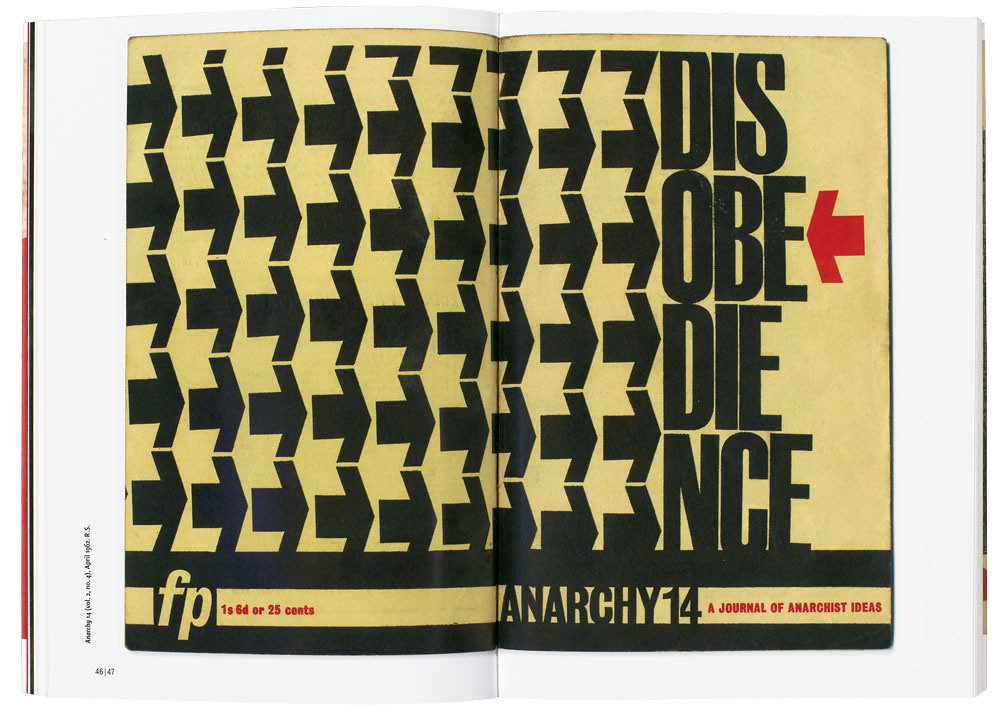

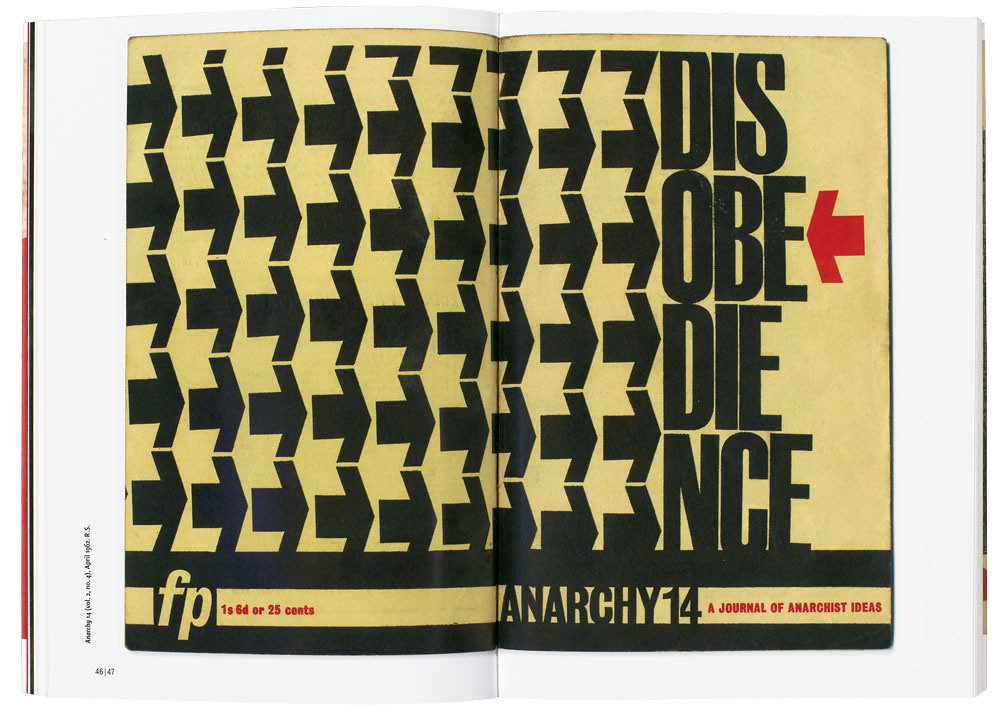

Ten years earlier, in March 1961, Ward had been the founding editor of Anarchy: A Journal of Anarchist Ideas. This small-format monthly was created to publish the kind of long and philosophical essays that could not be carried by its sister title, Freedom, an inky weekly newspaper that was already 75 years old. Ward commissioned Rufus Segar (b. 1932) to design his new periodical. At the time Segar was working for the Economist Intelligence Unit, creating charts, maps and other infographics for business, education and government. Moonlighting with Ward, he designed more than 100 of Anarchy’s 118 covers – all of which are reproduced at 1:1 scale in Daniel Poyner’s Autonomy.

Eschewing formulas and standard devices, Segar’s designs were diverse and often ingenious responses to the themes of each issue. He rarely met his editor, his brief often arriving on a postcard. Occasionally an illustrator was commissioned (Martin Leman’s Paolozzi-like collages of man-machines stand out). But more often than not Segar produced his own pithy drawings or worked with the images he had close to hand, such as clippings from newspapers, official reports and even family photographs. Like the best advertising of the day, the cover images were animated by sharp copy. The solitary pair of transparent spectacles in a pile of rose-tinted glasses on the cover of Anarchy 74 is catalysed by the cover line: ‘How realistic is anarchism?’

Segar’s techniques sometimes approached what Umberto Eco was later to call ‘semiotic guerrilla warfare’. Anarchy 79 (1967), for instance, was dedicated to the boiling ferment under way in the dictatorships and failing democracies of Latin America at the time. The cover takes the form of a montage, with correspondence to Segar from Ward, news clippings, as well as handwritten directions to a designer and the printer. These are more than technical instructions. A cutting from an official Ecuadorian newspaper demanding that the poor are swept off the streets to keep tourists happy is accompanied by handwritten marginalia: our ‘translator … says that the tourist is always wrong, if he goes to the temples, he has no social conscience’. On the back page, Segar instructs the designer to visualise the region’s demographic explosion: ‘Do a diagrammatic map of Latin America’. This, of course, is a message to himself, the other Rufus Segar at his Economist Intelligence Unit drawing board.

Interviewing Segar, Poyner tried to get him to talk about his double life as anarchist and design technocrat. The answer is unrevealing: ‘I found my forte in charts, maps and diagrams.’ But designers are rarely the best interpreters of their own work. And, in fact, Poyner turns to the one of the most skilled decipherers of design, Richard Hollis, for a technical analysis of Segar’s approach to typography and printing, in an essay entitled ‘Anarchy and the 1960s’. Poyner also includes a characteristically brilliant 1987 essay by the late Raphael Samuel, reviewing an anthology of essays from Anarchy.

Disappointingly, this structure keeps form and content largely separate. Graphic design historians have spent many words trying to establish the relationship of style to ideology. In the élan of Cuban poster designers working for Castro’s revolution, for instance, Susan Sontag saw ‘a culture which is alive … and relatively free of … bureaucratic interference’.

So what was the relation between the libertarianism of British anarchism and Segar’s designs? Was his eschewal of a credo or a singular style a claim on freedom? This was what Read had in mind when he wrote ‘it is always a mistake to build a priori constitutions’. Was Segar’s sharp-witted bricolage technique a political declaration (as it was for the Situationist International, his contemporaries on the Continent)?

And if, as Samuel suggests, British anarchism faltered just at the moment when it was most needed, the revolutionary year of 1968, should the same charge be levelled at Segar’s designs? To judge from the images in this book, they would stand up well to this kind of scrutiny.

Cover of Autonomy, designed by Peter Brawne, Matter.

Top: spread featuring the cover of Anarchy 14, vol. 2 no. 4, April 1962.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 85 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.