Spring 2019

Hard-working hooligans

Hard Werken

75B

Henk Elenga

Kees de Gruiter

Gerard Hadders

Tom van den Haspel

Willem Kars

Rick Vermeulen

Book design

Design history

Graphic design

Reviews

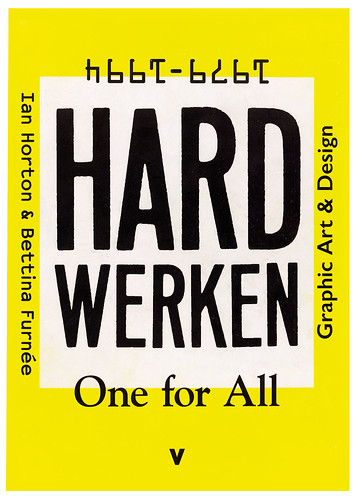

Hard Werken: One for All 1979-1994

By Ian Horton and Bettina Furnée. Designed by 75B. Valiz Publishing with Stichting Kunstpublicaties Rotterdam, €35

Scan the pages of recent graphic design history, and its coverage of the rule-breaking mantras that enraptured the field in the 1980s and 90s, and you find several traces of Hard Werken, the interdisciplinary design studio and magazine. The ‘core’ group – Willem Kars, Kees de Gruiter, Tom van den Haspel, Gerard Hadders, Rick Vermeulen and Henk Elenga – who had studied at the Rotterdam Academy of Fine Arts, in subjects that ranged from painting to advertising, registered the Hard Werken studio as a commercial entity in 1980, a year after they launched the first issue of Hard Werken magazine. In the following fourteen years, Hard Werken produced some of the most enthralling graphic design in Europe, epitomised by their 1981 poster for ‘China: Life and Work’, in which a cut-out figure, dazzling pattern and riotous typography compete in a typically crude assemblage. Yet, despite their varied and remarkable output – which also includes numerous advances into the fields of exhibition design, product design and staged photography – a search through published literature will yield few substantial results. In their book, authors Ian Horton and Bettina Furnée aim to fill this gap in Dutch and international design history.

Their comprehensive study traces a neat arc, from the subsidised heaven of the 1970s and 80s, an environment without which Hard Werken would not have survived, to the aggressive cuts of neoliberal policy and the emerging dominance of computer technology in the 1990s, both cited by the authors as partially responsible for Hard Werken’s eventual dissolution in 1994. The book’s desire to interweave biography, cultural history and technical description leads to some rather dense passages. Like many chronicles of Dutch design in the past century, the text is riddled with institutional bodies and their acronyms, which may throw the lay reader. Yet, for those happy to invest the time, the reward is worthwhile. It is helpful to understand, for example, that the radical use of printing processes in the studio’s early years, most notably on the covers of the Hard Werken magazine, were not a product of ingenuity alone, but also a result of Kars’s position as manager of the Grafische Werkplaats, an artist facility housing specialist printing equipment. As Horton and Furnée note, ‘They had direct access to technical support, could make proof copies at any stage in the process […] a very different situation from the more usual commercial relationship between designer and printer.’

Cover of Hard Werken: One for All 1979–1994.

Top. Spread showing Hard Werken’s designs for Bert Bakker publishers and Museum Journaal, alongside an ad for Hard Werken T-shirts.

This approach, to probe the pressures and opportunities of the studio’s position, both historically and geographically, is continually fruitful. Crucial themes that may usually fall by the wayside for their lack of direct relevance are here explored in a series of complementary ‘insert texts’, written by additional contributors. Surveys of Rotterdam’s gallery scene, 1970s self-publishing and Max Bruinsma’s ‘Unicorns in the Geometrical Park’, a case study in the differing cultural attitudes of Rotterdam and Amsterdam, enrich the historical texture of the book. These position Hard Werken within what the authors term the ‘complex cultural networks operating in Rotterdam at the time’ and its ‘relation to the city’s own emergence as a creative hub in the 1980s’.

Given the artistic invention of the studio’s portfolio, an observation pressed upon the reader throughout and emphasised in 75B’s eclectic design, the authors propose little novel analysis. The stimulating effect of visuals, such as Van den Haspel’s painted stage designs for the Dansproduktie dance organisation or Hadders’ early use of the Paintbox software, is often underplayed. But in a book with more than 400 reproduced works, including long-term collaborations with the International Film Festival and Bert Bakker publishers, many of which cannot be found outside of city or personal archives, the decision to focus on inclusivity over interpretation should be applauded. The foremost contribution of Hard Werken: One for All, therefore, may lie in the extent of its research, and the authors’ proficiency in tying together the diverse strands of material that contributed to the rise and fall of this epochal Dutch studio.

Alex J. Todd, design historian and writer, London

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.