Summer 1993

History’s role in the studio

Beatrice Warde

Ellen Lupton

April Greiman

Neville Brody

Andy Warhol

Robert Brownjohn

Ivan Chermayeff

Cipe Pineles

Design history

Reviews

Modernism and Eclecticism

New York, 20-21 February 1993Now in its sixth year, the ‘Modernism and Eclecticism’ symposium organised by Steven Heller in conjunction with the School of Visual Arts continues to fulfil its role as a useful forum for broadening in the general level of understanding of American graphic design history and for encouraging much-needed discussions of design issues and methodology. As the graphic design profession considers possible new directions, analysis of its past and the development of theoretical constructs becomes increasingly important. The deliberately eclectic nature of the topics presented during the symposium – from women’s and minority positions in design history to popular culture themes such as skateboarding and Disneyland – provide an important stimulus for reflection and debate.

A number of papers sought to broaden the approaches currently employed to examine American graphic design history. The development of an appropriate and coherent methodology for documenting American graphic design at present falls somewhere between a pioneer’s show-and-tell and more thoughtful attempts to address the complex cultural, political and social issues which inform graphic design ideology and style. Frances Butler’s discussion of the new Demotic as read in the work of Neville Brody, April Greiman and Emigre magazine put forward an interesting if ineffective method for analysing contemporary work.

Other areas of methodological concern covered included an investigation of gender issues. Design history – particularly in the US – has tended to reinforce the notion of the design community as a male domain, and the symposium certainly had its fair share of ‘great man’ presentation: Ivan Chermayeff reflected on the work of American pioneer Robert Brownjohn; Al Gowen reminisced about Buckminster Fuller as a teacher; J. Abbott Miller charted the rise of media gurus Marshall McLuhan and Andy Warhol. The inclusion of three papers on aspects of women’s roles within graphic design and advertising in the twentieth century was a welcome first step towards widening established parameters of design history writing and discussion.

My own presentation highlighted the career of the American type historian and designer Beatrice Warde, who was publicity manager of the British Monotype Corporation from 1927 to 1960 and a figure to be reckoned with in international graphic design circles at a time when women were rarely employed by the typographic and printing industries. Ellen Lupton focused on images rather than their creators in ‘Mechanical Brides: Women and Machines’ (to be the subject of a forthcoming exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt), an analysis of how American advertising imagery depicted women within the newly defined arena of the workplace in the early twentieth century. Presented as a new breed of homogenised workers in ‘pink collar ghettos’, telephone receptionists, for example, were portrayed as ‘mediators of messages’ with male office employees cast as senders and receivers of information. Thus work that involved the telephone was readily stereotyped as belonging to the female domain.

Estelle Ellis, president of Business Image in New York, described her involvement as promotion director in the creation and evolution of the teen market in magazine publishing through the successful launch of titles such as Seventeen and Charm. Working alongside Cipe Pineles and Helen Valentine, Ellis and her team challenged conventional editorial policy by introducing articles on modern art, contemporary politics and social concerns. Seventeen was also innovative in design terms and commissioned a range of ‘outstanding illustrators, photographers, and artists such as Ben Shahn and Robert Gwathmey’.

If the intention of the symposium is to raise awareness among design professionals, educators and historians, and to realise the need for pushing an understanding of design and its history beyond conventional boundaries, then why has so little progress been made in the acceptance of design history as an integral part of the process? Has the series moved the debate beyond its original starting point? In particular, why is the majority of American designers, historians and educational institutions so slow to acknowledge the need to develop and promote new design history methodologies?

In Britain the educational structure of art and design colleges provides a favourable environment for graphic design history to evolve as a formal discipline. Many American institutions have a less defined curriculum, and graphic design history has usually been taught by design professionals who draw heavily on a combination of personal experiences (often anecdotal) and conventional art historical approaches. Until the US design profession advocates an active role for graphic design history in educational and studio practice, new directions will not be readily forthcoming.

While conferences such as this – well-attended by practitioners, historians and students alike – provide lively forums for discussing such issues, the ideas put forward must be acted on. If the issues raised at the symposium fail to have any impact, it may be that ‘Modernism and Eclecticism’ will go the way of a number of prominent graphic design conferences in America which no longer exist.

Teal Triggs, design historian, Ravensbourne College of Design and Communication

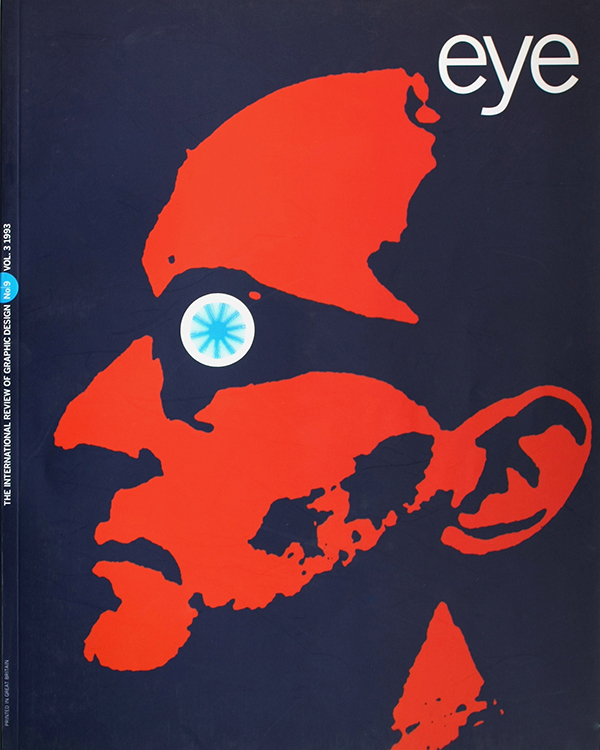

First published in Eye no. 9 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.