Friday, 12:50am

1 October 1993

How they lost the paper war

Paper’s troubled PR

When Mary Blake, the paper expert at Greenpeace’s London office, stood up to ask a question at the last World Pulp and Paper conference, an almost tangible ripple of hostility went through the audience. After question time, in what should have been a coffee break, Blake was surrounded by half a dozen people desperate to convince her that her claims about the effect of the paper industry on the environment were wrong. Voices were raised and tempers barely controlled: it was far from the urbane trade talk that had characterised the rest of the two-day event …

Read the full article here, eyemagazine.com/feature/article/how-they-lost-the-paper-war

Julia Thrift, design journalist, London

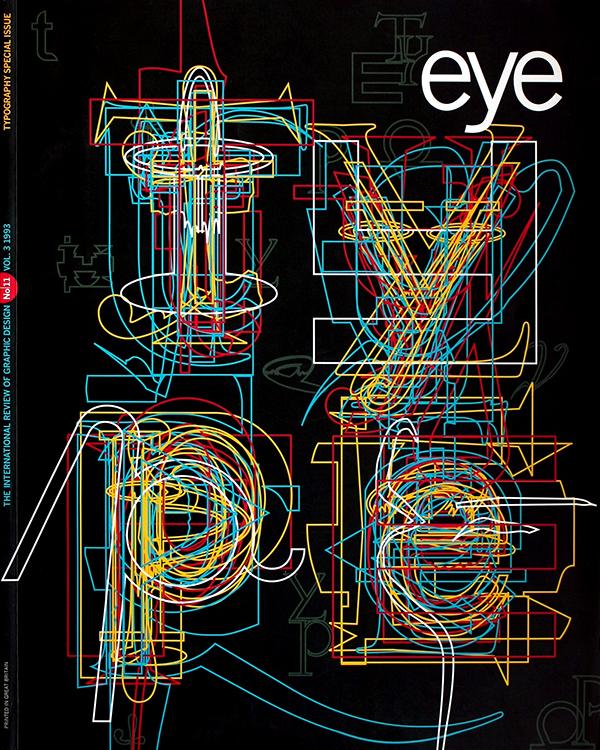

First published in Eye no. 11 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.