Spring 2019

Information and emancipation

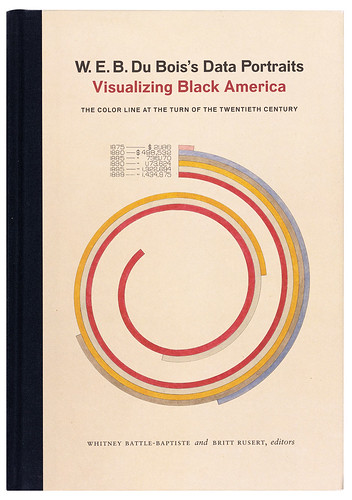

W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America, The Color Line at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

By Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert (editors). Designed by Benjamin English. Princeton Architecture Press, £21.99, €29.95

This book brings to light an audacious moment in the long career of civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963). It took place during the first McKinley administration, at the end of the Gilded Age and the rise of Jim Crow laws. Du Bois, then a professor at Atlanta University in Georgia, enlisted a group of students to prepare a set of data portraits for the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris. Editors Battle-Baptiste and Rusert, who have published these graphics for the first time in book form, tell us that ‘Du Bois and his team used Georgia’s diverse and growing black population’ to produce their graphics ‘as a case study to demonstrate the progress made by African Americans since the Civil War’. The first 36 plates were part of ‘The Georgia Negro: A Social Study’. The 27 additional plates had the title: ‘A Series of Statistical Charts Illustrating the Condition of the Descendants of Former African Slaves Now in Residence in the United States of America’.

These diagrams communicate the social and economic status of the African-American population of the country in general and Georgia in greater detail. The title chart featured hemispheres of the New World of North-South America and Old World of Europe-Africa-Asia connected by ‘routes of the African Slave Trade’. A few charts show time series going back to 1750, but the majority focus upon the growth of land ownership, personal wealth and professional status among ‘Descendants of Former African Slaves’ in the 35 years following the Civil War.

When you turn the pages of this book, you are looking at reproductions of texts and images meticulously drawn on 22 by 28 inch boards. A photograph from 1900 shows us the context in which they were displayed: the corner of a room in the Pavilion of Social Economy. There is one tier of bookshelves and three tiers of mounted displays. The pages we look at today were mounted on hinged frames to permit the visitor to see as many as possible in the small space. The graphics are clear and bold, though the lettering appears rather thin and light by contemporary standards. The edges of most boards are frayed and torn.

Cover and image from W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits. Design: Benjamin English.

Top. A map indicating the share of land held by blacks in Georgia, US, at the end of the nineteenth century.

The great value of this book is to see these graphics handsomely printed, out of context, as single images. Though a century old, they look familiar. Bars on one show the growth of land ownership, on another the distribution of income and expenses across seven income levels (with the invitation ‘for further statistics raise this frame’ to view the data behind the chart). Four monochromatic circles show the growing number of black teachers in public schools.

Several stand out for their original visual strategy. Designer Silas Munro points out their resemblance to Modernist art: ‘Made a decade before the rise of dominant European avant-garde movements, these works predate modular design elements often considered to have their origins in Russian constructivism, De Stijl, and Italian futurism’. We may see Malevich when we look at spirals of ‘City and Rural Population 1890’; Mondrian in the coloured rectangles of ‘Negro business men in the United States’ or Russolo’s Futurism when we see the jagged bolts that contain totals in ‘Assessed Valuation of All Taxable Property Owned by Georgia Negros’. Such comparison undermines the polemic drive for attention that lies behind the designs themselves. There were few conventions to compare them to when these plates were made and there was no Modernism for them to imitate or reflect.

Each design is an individual cry for attention, but what echoes across all 63 plates is the demand for visibility and respect among a 7.5m-person community. As one chart makes clear to the audience milling around the Paris Universal Exposition, the African-American population of the US in 1900 was larger than the populations of Sweden and Norway combined, or Bavaria. Du Bois’s charts were a demand to be noticed.

Paul Kahn, information designer, Boston, US

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.