Spring 2018

Japanese traces

Daijiro Ohara

Katsue Kitazono

Kensaku Goto

Kohei Sugiura

Kouga Hirano

Ryoji Tanaka

So Hashizume

Takasuke Onishi

Takeo Nakano

Toru Kaze

Toshiaki Koga

Yui Takada

Yusaku Kamekura

Tadanori Yokoo

Design history

Graphic design

Information design

Magazines

Reviews

Typography

Fragments of Graphism: An Alternative History of Graphic Design in Japan

Creation Gallery G8, Tokyo, 23 January–22 February 2018

This winter, the Tokyo exhibition ‘Fragments of Graphism: An Alternative History of Graphic Design in Japan’ asked some 60 graphic designers and studios to respond to the question: ‘What is the history of graphic design in Japan?’. By focusing mainly on young designers, the exhibition’s curators set out to tell an alternative history to the one that is widely disseminated.

The legacy of the graphic designers who have accompanied the country’s economic development since the Second World War is rather imposing. The official history includes figures such as Yusaku Kamekura, Ikko Tanaka and Tadanori Yokoo, while ignoring other contemporary figures.

Tokyo is fortunate in having many private spaces dedicated to design, among them Creation Gallery G8 (others include GGG Gallery at Ginza, and the Gallery 5610 at Omotesando). Here, curators Kiyonori Muroga [editor-in-chief of Idea magazine] and Tetsuya Goto, along with designers So Hashizume, Kensaku Goto and Daijiro Ohara, chose to adopt a wide-ranging approach. This proposed rephrasing might recall steps taken in Europe in recent years to set out the contours of a history of graphic design. In books and exhibitions alike, graphic design has been the subject of a great deal of examination, including ‘Communicate’ at London’s Barbican Centre in 2004; Graphic Design, History in the Writing, Occasional Papers, 2012; and Design Graphique, les formes de l’histoire, 2017, B42, among others.

The starting point for this exhibition is the impressive longevity of the journal Idea, founded in 1953 when Japan was in full reconstruction after the Second World War, and a decade before the country’s global economic boom.

The space is divided into three areas. The first room presents a selection of 47 books chosen by designers or studios. Each is accompanied by information on the designer who selected it, as well as text describing the book itself. The selection is broad and varied, including international work by Joost Grootens, Max Bill, Provo and Japanese publications including Typographics:ti magazine and Principles of Design Theory by Hideya Kawakita. A perusal of this library allows the visitor to dip into the work of some overlooked figures. Toru Kaze, a designer under 30, is interested in the artist and author Katsue Kitazono, who was a member of the Concrete Poetry group at the beginning of the 1920s. According to Kaze, Kitazono’s dual practice as author and typographer is unique for that era. Kitazono did not separate the text from its production and would go to the printers himself to keep control of the composition.

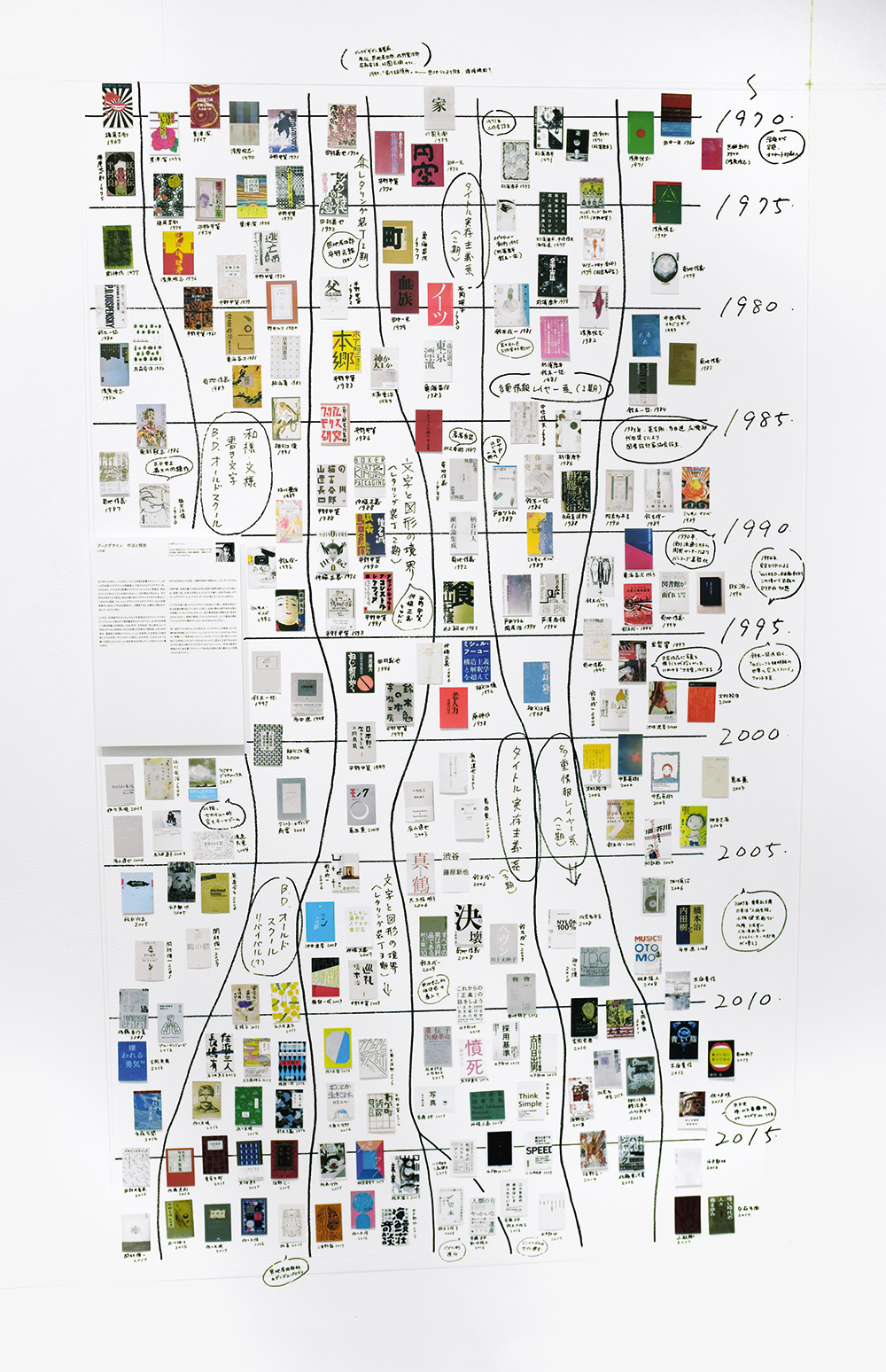

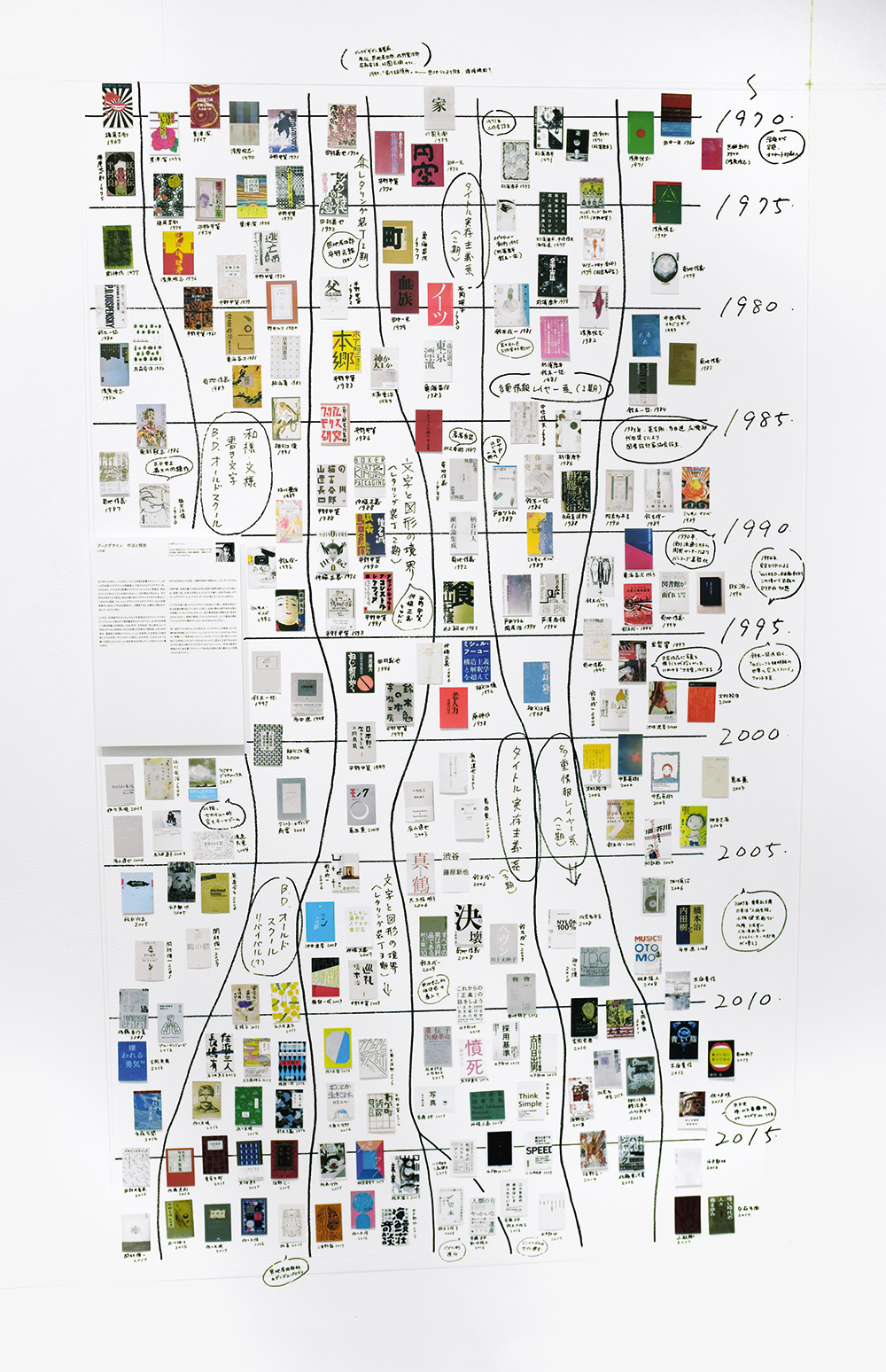

On the walls of the room there are displays made up of words taken from Idea’s contents pages, which form the word ‘Idea’ in Japanese. There is also a timeline, compiled by the design and typography historian Toshiaki Koga, that includes important milestones in the development of graphic design in Japan, technological developments linked to design practice, and key events in the country’s history.

A second room contains a dense display of thirteen 1x1.7m panels showing texts and visual material chosen by a further thirteen designers. Across these defined and thematic spaces the designer-curators reveal their influences and explore certain themes or personalities, such as the impressive typographic virtuoso Kouga Hirano, or Kohei Sugiura’s work. Studying these narrow spaces yields a richness and abundance; the Western visitor is bound to take away inspiration and references. The subjects are extremely varied: the popular and primitive imagery collected by Takasuke Onishi; the origin of the line from forms found in nature chosen by the typographer Daijiro Ohara; Ryoji Tanaka’s vision of numerical objects; Takeo Nakano’s vision of data information; forms of vernacular design chosen by Yui Takada; and a selection of articles from Idea to read or reread by So Hashizume.

In the third and final room the entire archive of all 381 issues of Idea is displayed for visitors to consult. Here, the patient and focused visitor is free to browse the impressive content produced by the journal for more than 60 years. Naturally, issue number one is an object of curiosity. It contains both a presentation of the work of French graphic artist Raymond Savignac and a text by Czech information design pioneer Ladislav Sutnar on packaging design. Sutnar appears on numerous occasions throughout the archive as an author, as does Yusaku Kamekura.

With this lineage in mind, the more recent issues of Idea present numerous contributions by graphic designers. The message seems to be clear: it is up to designers to take charge of their own history. Such an approach shows the extent to which design is nourished by multiple elements – whether these stem from the immediate environment, distant cultures or technological and economic developments. At the same time, the hierarchies inherent in the opposition between pop culture and intellectual culture are abolished – such an opposition being the preserve of the bourgeoisie. Designers are conscious of the need to engage in the identification of systems and processes that determine design. ‘Fragments of Graphism’ is a clear affirmation of a desire to engage designers to participate actively in writing the history of their own practice.

Top: Installation image of ‘Fragments of Graphism’ at Creation Gallery G8, taken by Kenta Hasegawa.

Alexandre Dimos, designer and principal, deValence, Paris

Translated from the French by Deborah Burnstone

First published in Eye no. 96 vol. 24, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 96 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.