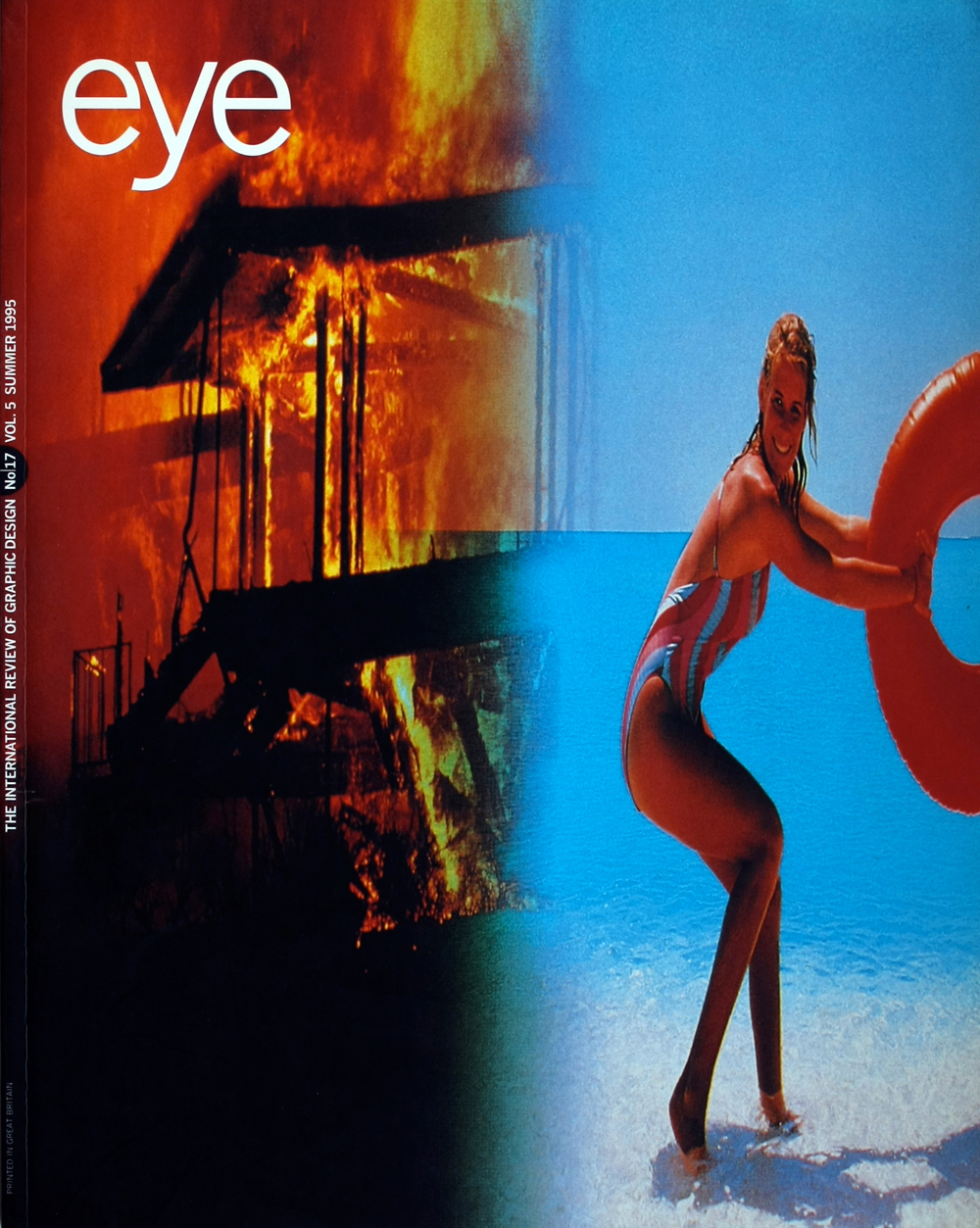

Summer 1995

Like the 1980s never happened

1994 British Design and Art Direction

The Designers and Art Directors Association of the United Kingdom

In 1987, Gert Dumbar won the D&AD gold award and two groups of his Royal College of Art students won silvers. At this time, Edward Booth-Clibborn, then chairman of the organisation, tried to seize the opportunity to woo a younger generation of designers into the D&AD camp by encouraging them to enter, and inviting them to be jurors. But it did not happen. The feeling was, ‘Why pay to have your work judged by people you do not respect?’ Three years ago Booth-Clibborn was ousted from power at D&AD, and whatever problems the new administration has solved since then, it has failed to address the continuing irrelevance of D&AD to a large section of the design community.

The sense that British graphic design is being misrepresented runs throughout this latest D&AD annual, subtitled ‘the 32nd annual of the best in British and international advertising and design’. A quick look at the contents suggests that the book is far from comprehensive: of its 533 pages, more than 320 are dedicated to advertising, eight to product design and just over 100 to graphic and environmental design. I doubt that such a balance truly reflects the relative size of the industries concerned.

The fact that the annual has been published so late makes it a little hard to remember much of the work included (which was done in 1993 and judged in March 1994). D&AD has always been slow in getting the book to press but to go beyond Christmas is inexcusable. Nevertheless, Abbot Mead Vickers’ Tony Kaye-directed Dunlop commercial and the Embassy ‘Tip’/‘Reg’ advertisements (best and worst of the year respectively) soon refresh the memory.

Designers always have reservations about advertising and these are not purely to do with perspective. The fundamental difference between advertising and design lies in the use of ideas. In advertising, they are stripped down to their bare essentials with little apparent interest in visual expression. The very notion of being new is quite out of place: advertising does not create visual styles, it keeps an eye out for developments in the design world, or elsewhere, and a year later, when the thrill has gone, lets them loose on a mass market. Too often it relies on the lowest common denominator, leaving little to chance and taking no risks. Advertising typography suffers in the same way, rarely leaving the centred axis and labouring under an irrational and ungrammatical obsession with capital letters and superfluous punctuation.

These prejudices aside, the new D&AD annual does have the feel of an accurate portrayal of the year as far as advertising is concerned, covering a wide variety of styles and approaches (largely because everyone in adland enters everything they have done over the preceding 12 months). However, the coverage of graphic design weakens the whole. Only larger and older design companies seem to take an interest in D&AD, with the result that the annual contains a small, unrepresentative cross-section of what is happening in the design industry. It is as though the last ten years never happened.

Why is Pentagram’s work for IDI and the Crafts Council so depressingly similar? Why do groups like The Partners love whimsy so much? And why does Roundel’s work for the railways suggest nothing of the business in question? Ideas stripped down are the dominant means of expression here, and some of the work is like a (bad) trip down memory lane: Michael Nash’s Christmas pudding packaging for Harvey Nichols is an example of an obvious idea expressed in the most crushingly banal way. Themes of respectability and nostalgia recur. Only the Nike posters by Robert Nakata and the record sleeves by Farrow (Pet Shop Boys) and Form (Delicious Monster) have any life to them.

The book suffers throughout from problems of arrangement. Advertising is split into two chunks (television/radio and print), separated by the design categories of graphics, product, environmental and editorial/books. This makes for a difficult read. Other concerns are about editorial decisions. The most interesting section in many ways is product design: this includes explanations of the context of each design, and reminded me of the American 100 Show catalogue in which captions provide useful contextualisation both by the entrants and the selectors.

The crafts categories in each section of the book beg questions too. When I was a D&AD typography judge three years ago, it became frustratingly clear that the entry-fee system prevents the best work from being judged: a great piece of typography in design, say, cannot win a craft award if it has not been entered in that specific category. I suggested that crafts would therefore be better selected from the main graphics and advertising sections, giving at least the possibility of the craft jury choosing what really was the best from the entire submission. But nothing has changed – craft entries still require a separate entry fee. If the annual as a whole is a poor reflection of the design industry, then the craft sections are even less representative.

In summary, this book reflects an organisation trying to reconcile two different industries. It continues to be the most telling barometer of the advertising industry, but for designers it is no longer perceived as the best showcase for work. This leaves D&AD’s claim to ‘set standards of creative excellence … and to educate and inspire the next creative generation’ with a hollow ring.

To represent design properly and fulfil these claims, D&AD has two options. The first is to appeal genuinely to a younger audience of designers and encourage them to submit work, thus making the selection truly reflect the nature of the business. The second is more radical but more truthful. Since the new broom at D&AD seems to have failed to make the organisation more relevant to the mass of graphic designers and to younger designers in particular, perhaps it would do best to acknowledge this fact and become ‘The Art Directors Association of the United Kingdom’.

Phil Baines, typographic designer, London

First published in Eye no. 17 vol. 5, 1995

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.