Spring 2019

Minard’s retirement plans

The Minard System: The Complete Statistical Graphics of Charles-Joseph Minard, From the Collection of the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées

By Sandra Rendgen. Designed by Benjamin English. Princeton Architecture Press, £45, $60

Sandra Rendgen’s The Minard System re-contextualises in book form for the first time the entire body of visual diagrams by Charles-Joseph Minard. Minard was an engineer whose life was devoted to the design, supervision and inspection of infrastructure projects throughout France. Born in 1781, he grew up during the first French Revolution and served the French states that changed (from republic to empire to monarchy to republic to empire) over his long life.

Minard is best known as the author of the diagram of Napoleon’s troop losses during the 1812-13 Russian Campaign, but this and other work were never published in book form. Instead they appeared in articles, pamphlets, teaching materials and lithographs printed either privately or through the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées (ENPC) where he worked. He was not part of any major scientific society and limited his theoretical writing to the annals of the ENPC. He made 50 of the 61 diagrams in the book between 1851, the year of his mandatory retirement from teaching and admin duties at the age of 70, and 1870, when he died at 89. He was an ‘amateur’ – a civil engineer who produced lithographic reproductions of visualisations that interested him and distributed them to influential members of the French meritocracy.

The diagrams reproduced in The Minard System are from the ENPC archives and the French National Library. Seen together they show the visual language he developed to represent the flow of goods and people through transportation networks. The ‘Minard System’ was a method for combining datasets of cotton imports, coal exports, or freight circulation with maps to assist the eye to see the distribution of goods over space. Minard represented numbers as thickness of line, splitting the line to show changes of flow and the distribution of goods between departure and destination.

This is similar to a technique created decades later by the British engineer Matthew Henry Phineas Riall Sankey to represent the thermal efficiency of steam engines, sometimes known as the Sankey diagram. Rendgen refers to Minard’s visual form as ‘flow maps’, and they resemble Sankey’s work in that both methods start with a width of 100 per cent to represent a value entering a flow, and divide or diminish the width as the flow progresses. It was Minard’s genius to draw this on a geographic base.

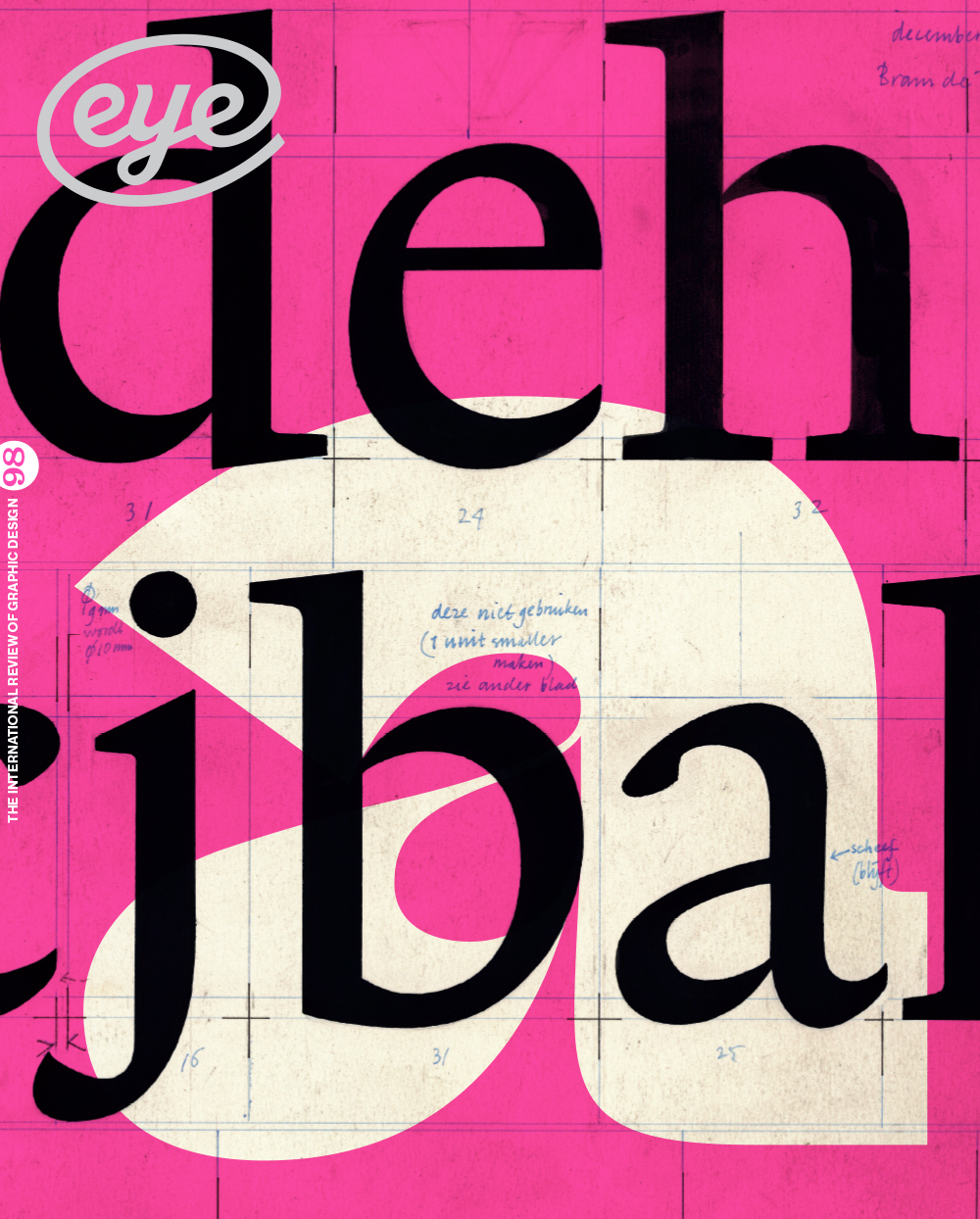

Cover shows detail from Minard’s celebrated 1869 diptych that shows ‘the progressive losses in men’ in armies led by Napoleon (1812-13) and Hannibal (218 BC).

Top: Spread from The Minard System shows detail and full print (1862) from Minard’s consistently scaled and coloured series of diagrams about the transport of mineral fuels.

Cartographers have criticised the ways he freely distorts maps to present his chosen data story, but it is clear why Minard made this choice. For example his diagrams showing raw cotton imports into Europe before, during and after the American Civil War show how United States cotton exports dominated the European market in 1858; he flattened the North American coast; made England larger than Spain and France; and distorted the distance between Florida and a Caribbean that contains only Cuba and Haiti. We see the story he seeks to tell – the collapse of US exports against the growth of imports from India and Egypt.

We also see the flow of travellers, wine, livestock, cereal and immigrants in 1858: the flow of people from Africa, India and China to colonies in the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, Australia and California, plus Europeans going to the US, Canada and Australia.

The cover shows a detail of Minard’s 1869 diagram of Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign, part of a diptych also showing Hannibal’s loss of men during his invasion of Italy in 218 BC. Edward Tufte reproduced the diagram in The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, claiming it ‘may well be the best statistical graphic ever drawn’. As Rendgen notes, this image has become, like Van Gogh’s Starry Night, a design for T-shirts and coffee mugs. Minard was well aware of the political situation that would lead to the Franco-Prussian War. He may have hoped that by distributing this print, which illustrated the flow of death that resulted from military hubris and miscalculation, he could prevent that disaster. Instead, the French army was routed, he fled Paris ahead of the Prussians’ siege and he died of a fever, leaving behind the design that made him famous.

Paul Kahn, information designer, Boston, US

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.