Autumn 1990

Multimedia machine

Tools: What comes after the Mac?

NeXT: the first real challenge to the designer's favourite computerWhat comes after the Mac? Nico Macdonald considers the first real challenger to the designer’s favourite computer. By Nico Macdonald

At first sight the NeXT computer shows every sign of being a second generation Macintosh. It has the same type of interface and the same apparent ease of use that has made its predecessor the almost invariable choice of graphic designers out to buy a computer. But it improves on them in ways that could not have been anticipated when the Macintosh was designed. The NeXT is able to cope with demands that the Macintosh can only handle with extensive upgrades and add-ons. And it also anticipates the developments in networking and communications we can expect in the next few years.

Like the Macintosh, the NeXT is the creation of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs 9he has also called his new company NeXT). The NeXTcube is a 12-inch black box which comes with a 17-ince 94 dpi (dots per inch) monitor capable of showing four shades of grey (colour monitors are scheduled for early 1991). The NeXTstation is similar in size, has the same processor, but fewer options for storage and expansion. There is an optional 400dpi laser printer. The NeXTcube can be configured with internal hard disk, or an optical disk which offers 256 megabytes of storage – a phenomenal amount by today’s standards.

Initially the NeXT was aimed at the education market, but it is now being directed at business users and publishing. On grounds of price alone it compares very favourably with the Macintosh. The recommended price (NeXTstation £3,225; NeXTcube £5,155; laser printer £1,160) is considerably lower than the nearest equivalent system, and upgrades to faster processors will be possible without the need to buy a new computer.

The NeXT interface is the now familiar combination of pull-down menus for commands; icons representing files, folders and programs; a mouse for selecting and moving items on-screen; and a windowing system for viewing open files. What the new machine adds to this formula is shading to indicate options and a more elaborate screen syntax. A panel of program icons on one side of the screen allows easy switching between tasks, and menus that drop down at a mouse-click mean you don’t have to move to the top of the screen, as you do with the Macintosh.

An even more useful improvement is the way which typographic and design elements are rendered on the NeXT’s screen. Although it is possible to combine graphic elements (type, rules, tints and images) in the same computer printout by using a common software language to describe them (PostScript is the current standard), most computers use a different language to draw the screen, with crude or at least imprecise results. The NeXT, on the other hand, both draws the screen and prints in PostScript (the output of the laser printer, with almost twice as many dots as most other printers, is particularly clear). Its screen is, if anything, even more sophisticated than the printout, since it can display elements with degrees of transparency – a concept that NeXT want PostScript to feature as standard.

In its short history the NeXT has acquired the basic programs need for graphic design work: page make-up, line-based drawing, scanning and image editing, and text manipulation. The quality of these programs does, of course, depend upon the authors of the software, but there would seem to be much to recommend the NeXT as a platform for third-party developers. According to NeXT, programming has been made almost as easy as using a program. The NeXT interface, known as NeXTstep, has been licensed to IBM, which will make software development more worthwhile because of the number of potential users.

Perhaps the most significant advantage of the NeXT rests in its operating system, Unix. This allows several programs to be run simultaneously and to make “calls” to each other to perform certain functions (for instance a graphics program asking a mathematical program to solve an equation in order to plot a graph). Given the nature of page make-up programs, this multi-tasking facility is potentially invaluable.

Communication is, in fact, the watchword of the NeXT, which packs in a formidable array of communications tools: networking hardware, electronic mail and fax modern software, sound-digitising hardware, a high-quality speaker and an add-on video board (the NeXTdimension). Although these capabilities were developed primarily to facilitate group working, they are early indications of what media specialists like to prophesy as a brand new age of “multimedia”, in which moving graphics, text, video and sound will merge to form new styles of multi-layered electronic communication. The full potential of the NeXT will only be realised when, at least for some types of communication, we abandon the printed page altogether and send digitally generated documents not to the typesetter and printing press, but to other computer screens.

But this, quite clearly, is some way in the future. For designers working today, the NeXT has significant limitations. It has a system of filing and networking protocols that is harder to learn than the Macintosh’s equivalent functions. The interface, although slicker than that of the Macintosh (or the Mac-like Windows interface used on IBM-compatible computers), is not as smooth to use and lacks many of they keyboard shortcuts that help to avoid excessive ‘mousing around’. Font management, a significant problem on early Macintoshes, has not been properly addressed. And most crucial, perhaps, the lack of service bureaux with NeXTs is bound to hamper the production of final artwork.

Most of these problems will be solved in time, but for now the Macintosh still provides most of the facilities that graphic designers need. Where the NeXT has real potential is in areas of design which hinge on collaboration and require the storage and processing of large amounts of information. The computer could still come into its own in publishing, particularly for long technical documents, magazines and newspapers where networking allows designers, editors and writers to work on different aspects of the same document. If the NeXT can build a bridgehead among such users, it will be well positioned for the multimedia design revolution should it eventually occur. Until that time, the NeXT can expect to meet stiff competition for designers’ loyalty – competition which the Macintosh did not have to face. The future of the NeXT as a graphic design tool may be uncertain, but it is sure to force other manufacturers to respond to its innovations, the second time Steve Jobs has pulled off such a feat.

First published in Eye no. 1 vol. 1, 1990

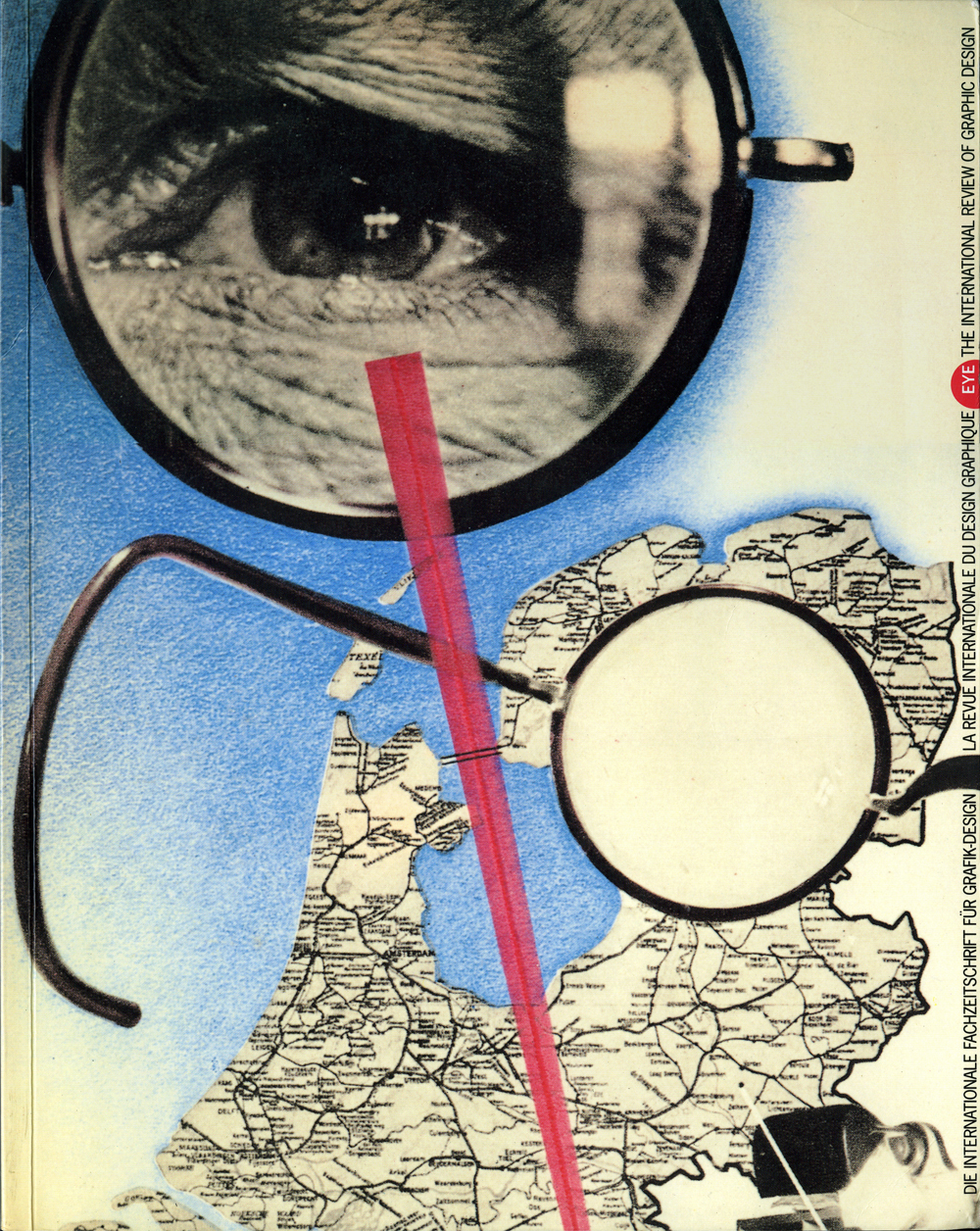

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.