Autumn 2009

No way to treat a woman (designer)

Women of Design

By Bryony Gomez-Palacio and Armin Vit<br>How Books, £15.99elles@centrepompidou

Centre Pompidou, Paris <br>27 May 2009 – 24 May 2010

A couple of years ago I wrote a series of essays whose working title was ‘Random Lessons in Joie de Vivre’. At the last minute, the marketing department must have prevailed, and I was told my book would be released as The Art of Being a Woman. I was mortified. It had never been my intention to tell readers how to be feminine! I tried, but could not get out of the deal. Not surprisingly, the book didn’t do very well.

I should have known to steer clear of titles with the ‘W’ word in them, yet I couldn’t resist when I was asked to be included in Women of Design, an illustrated directory of female graphic designers. And once again, upon

seeing the end result, I felt deeply humiliated. Suffice to say: the designers are introduced alphabetically, as April, Barbara, Deborah, Katherine, Louise, Meredith... their first names displayed twice as large as their last names.

For a designer active in a field largely defined by male practitioners, being identified as a woman is a source of instant discomfort. The authors of Women of Design have done their best to avoid any semblance of radicalism. They have adopted an overtly friendly, late-night-TV interview style, fudged generational gaps by defining the women in broad chronological terms (‘trailblazers, pathfinders, groundbreakers’), and peppered the text with so many teasers, pull quotes and highlighted statements that it looks like a camouflage pattern designed to conceal rather than reveal the singularity of each artist.

Flipping through the book is like speed dating. After a while all the entries look the same, and you cannot remember whether it is Chee, Emily, Joyce or Julie that is the celebrated i-D magazine editor. Lumped together in this broad category, does nothing to increase a designer’s self-esteem or prominence as an expert in her field. The camouflage layout is no coincidence: the book is an undercover operation.

In the questionnaire sent to participants, one question stood out: ‘How do you use your time?’ One would never pose this question to a man but we did not take umbrage. On the contrary, we understood that this was our one opportunity to brag about our independence. Out of 72 women listed, only a dozen mentioned taking care of their children, and a handful talked about their husbands, as if being mothers and wives was detrimental to their credibility. It was left to Laurie Haycock-Makela to put the rest of us to shame with a wry comment: ‘I have been deeply influenced by three wildly flawed men,’ she wrote, naming her brother and her two husbands. ‘I teach my son and daughter the power of detachment, passion and knowledge [which I learned from the men], and they now hold all the secrets of the world.’

Quite a few women spoke about their work with intelligence and sincerity, but none had the courage to confront the dark side as Haycock-Makela did. We took our cues from the tone and the tenor of questions prompting us to elaborate on our career, egging us on to describe our accomplishments. Instinctively, we produced generic statements, assuming, wrongly perhaps, that the editors expected us to be on our best behaviour. So, truth be told, we share responsibility for the ‘lite’ content of Women of Design with its editors. In hindsight, people such as Gael Towey, Emily Potts or Chee Pearlman, who, for reasons unexplained, did not dignify their presence in the book with answers to the questionnaire, come out looking good, while the long-winded participants give the impression of being insecure.

Can one address the issue of women’s representation as artists in our culture without falling into the trap of sweeping generalisations? A current retrospective at the Pompidou in Paris proposes a remarkable alternative. Called ‘elles@centrepompidou’, it features the work of 200 women artists worldwide, among them some of the graphic designers included in Women of Design, such as April Greiman and Irma Boom, and some that are sorely missing: Lella Vignelli, Zuzana Licko and Lorraine Wild.

Most notable about the Pompidou show is the way the curators were able to underplay the similarities between the various approaches of the artists in order to highlight their singularity. They cleverly created half a dozen thematic sections that did not categorise the works of art but left them open to interpretation: ‘free fire’, ‘wordwork’, ‘immaterials’, ‘eccentric abstraction’. You wander, lost in a labyrinth of contradictory manifestos, unable to comprehend it all but in a delicious state of ‘alert stupor’ (to quote Maira Kalman, one of my favourite woman designers). Though disconcerting, it is the closest thing to an Alice-in-Womenland experience.

Each ‘woman of design’ is an isolated phenomenon, and her history, her approach and her contribution to the field is as unique as she is. In order to pay tribute to female designers, however, we must first get rid of the ‘we’ in ‘women’.

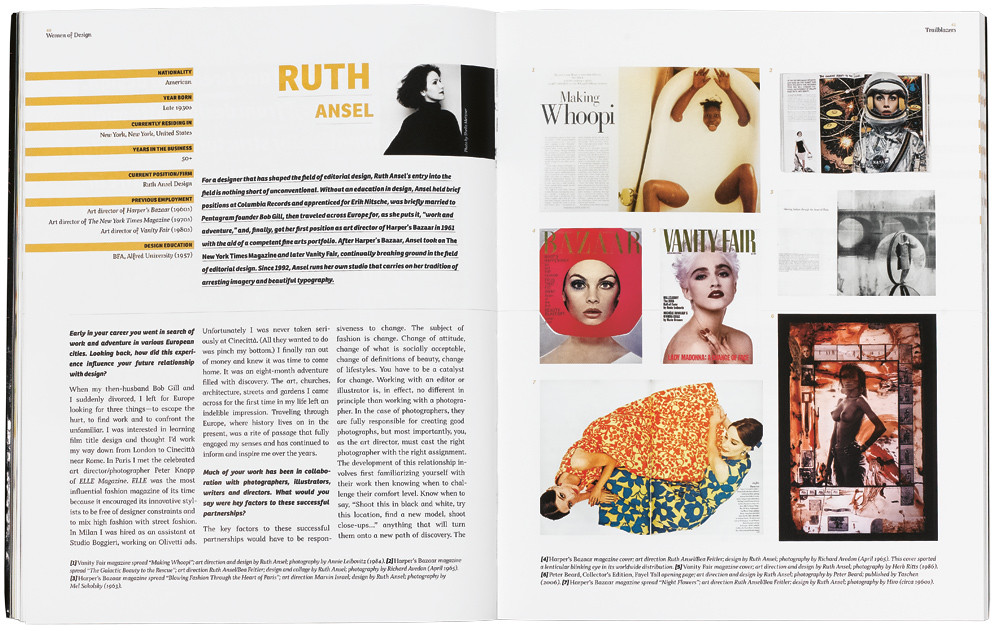

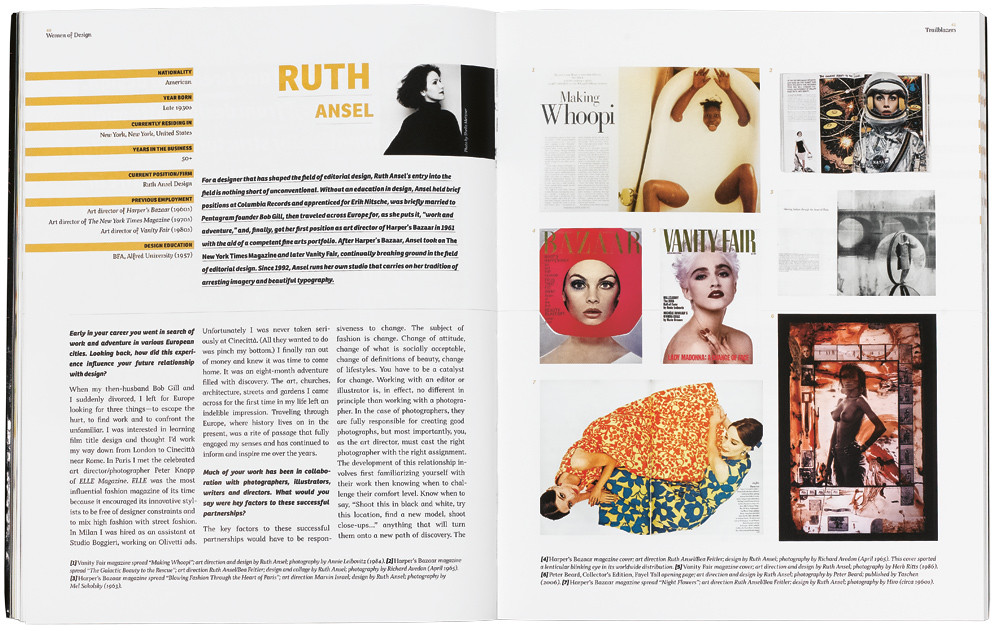

Top: spread showing work by the American designer Ruth Ansel, former art director of Harper’s Bazaar (1960s), The New York Times Magazine (1970s) and Vanity Fair (1980s).

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.