Autumn 2019

One hundred years new

New Typographies: Bauhaus and More: 100 Years of Functional Graphic Design in Germany

By Patrick Rössler. Design by Marcus Holland. Wallstein Verlag, £34

Jeremy Aynsley’s Graphic Design in Germany 1890-1945 was published almost twenty years ago. Professor Rössler’s new and quite different book covers the same subject, the same period. Aynsley is cited by Rössler as a ‘major source’. The reader will ask if this new book revises the story, or tells it in a different way.

New Typographies originated in a series of articles in the journal Novum in 2017, timed to mark the centenary of a four-page Dadaist broadsheet, Neue Jugend. Designed by John Heartfield and George Grosz, Neue Jugend, Rössler points out, was identified by Jan Tschichold as ‘one of the earliest and most significant documents of the New Typography’. (There are no footnotes and without a copy of Tschichold’s The New Typography to hand, the reader will have to trust Rössler’s citations.)

In English the word ‘Typography’ refers to the art of arranging type, whereas the German word Typographie embraces all kinds of graphic design. Adopting the plural ‘New Typographies’ allows Rössler to reproduce ‘less popular and even homespun adaptations’ of Modernist avant-garde graphics, far outnumbering ‘well-known icons of the New Typography’.

The book is divided into five parts. The first, ‘Innovation’, opens with ‘The new typography – the origins of a movement’. It first quotes László Moholy-Nagy’s maxim: ‘Typography is a tool of communication. It must be communication in its most intense form.’ Tschichold set out the New Typography’s programme in practical detail. It called for the replacement of Fraktur typeface with roman (Antiqua) designs – sans serif preferably. Ornament, other than lines and geometrical forms, was to be suppressed. Unprinted areas of a design were to be thought of as part of the visual effect. Page layout was to be asymmetrical, and formats standardised.

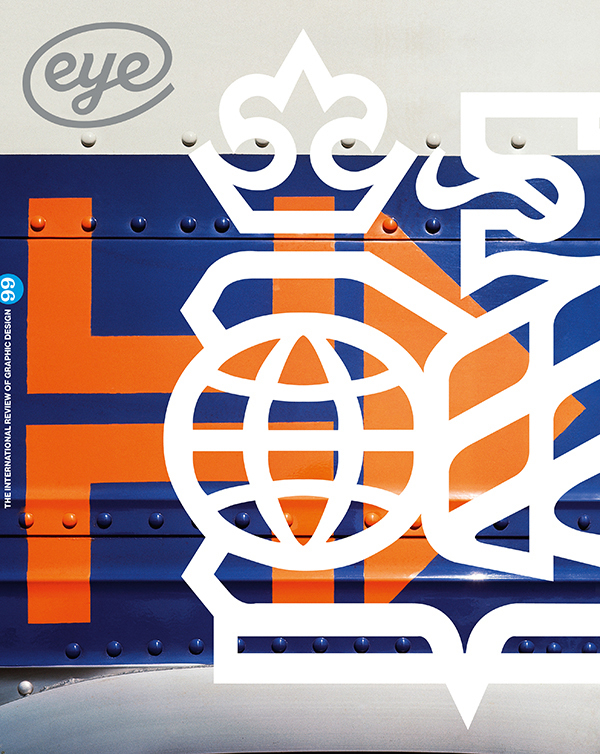

Cover of New Typographies: Bauhaus and More: 100 Years of Functional Graphic Design in Germany. Design by Marcus Holland.

Top. Spread from New Typographies, featuring the work of Zdeněk Rossmann, František Zelenka and Ladislav Sutnar.

Rössler underplays the roles of Italian Futurism, Russian Constructivism and Dutch Neo-Plasticism (Mondrian and Van Doesburg) in suggesting new graphic ways and means. While they are all cited by Tschichold, Rössler questions his failure also to acknowledge the influence of the ‘simplified visual language’ of pre-First World War pictorial posters (Sachplakate) – quite foreign to the spirit of the New Typography in their painterly illustration. But their mention is a foretaste of the unfocused selection of works shown later in the book.

Professor Rössler has written extensively on Bauhaus designers, the subject of the second section of ‘Innovation’, and he sees the school as the ‘catalyst for the entire New Typography movement’. But in the second part of the book, ‘Diffusion’, Kurt Schwitters is quoted, paradoxically warning of ‘a danger that our movement could be seen as influenced by the Bauhaus’. Schwittters was organiser of the modernising Ring neue Werbegestalter (The New Advertising Designers’ Circle). A second group to define the new graphic design were the 26 contributors to Gefesselter Blick (Captivated Look), a compendium that printed personal statements and examples of their work. The only connection with the Bauhaus in both these groups was László Moholy-Nagy – appropriately, since his formulation of Typofoto (the integration of typography and photography in graphic work) represented the essence of the New Typography, a rejection of hand-drawn lettering and illustration.

‘Diffusion’, carries examples from the most well known of the non-German Modernist designers in Europe, in particular Czechoslovakia, but the representation of Soviet work is thin, and there is nothing from Poland or Italy, whereas Rössler includes dozens of examples of ‘homespun adaptations’ of the New Typography, unremarkable aesthetically but with some stylistic elements borrowed from its pioneers. Tschichold is rightly represented by more than 40 illustrations and John Heartfield by twice that number.

In spite of his membership of the Ring and inclusion in Gefesselter Blick, Heartfield’s powerful photomontaged book jackets do not fit comfortably with the likes of Tschichold’s formal subtleties.

Political questions are raised in ‘Diffusion’, where a section devoted to Frankfurt illustrates the optimistic vision of social democracy in the Weimar Republic. Led by a huge housing programme, the city of Frankfurt was promoting itself to its own citizens and the outside world as a blueprint for a twentieth-century urban community. Graphic communication was essential to the project. The public was informed of developing policy, exemplified by the square-format monthly Das neue Frankfurt and its supplements that carried recommendations and details of well designed products. Designed by Hans and Grete Leistikow, the text was set in the new Futura typeface.

Rössler’s third section, ‘Media’, is split in three: ‘The Book and its Jacket’, ‘Film & Photo’ and ‘Illustrated Magazines’. Here the relation to the New Typography, apart from a Tschichold book, is rarely apparent. The author writes of ‘the diversity of 1920’s new Typographies’, perhaps an excuse for allocating a whole page earlier in the book to ‘an outstanding example for functionalism in book typography’. Technische Zeit, designed by Max Burchartz (who was acknowledged by Tschichold as a Modernist pioneer), is outstanding, but it is untypical; it was produced as a limited edition. The section on film and photography opens with a Tschichold film poster, but shows only the covers of books by Werner Gräff – the avant-garde specialist in film books – revolutionary in their interweaving of text and image.

In 1932 Das neue Frankfurt was renamed Die neue Stadt (the new city) and closed the following year; the National Socialists had come to power. Rössler confronts the situation directly. Nonetheless, the beginning of his ‘Epilogue’, the fourth section, is given the lame title, ‘Defying NS Stupidity – or Aligned?’ If Modernism in general is out of favour, regarded as expressing Bolshevik tendencies, what are designers to do? The distinction between medium (of Modernist objectivity) and message (of authoritarian nationalism) was blurred. The Modernists had developed, in particular in the use of photography and photomontage, a powerful method.

Given the latitude Rössler has allowed himself it is not surprising that there is little difference in style between the pre-Nazi time and graphic design under the new regime. However it is inadequate for Rössler to write of a designer being ‘an aesthetic resistance fighter against the criminal Nazi system’, at a time when colleagues were being arrested or murdered. Several left for Soviet Russia, the Leistikows and a group of Bauhäusler among them.

Some designers who fled the Nazi regime turn up in the final section of the ‘Epilogue’. Former Bauhäusler such as Herbert Bayer (who initially played for time), György Kepes, and Xanti Schawinsky left for the US. The final pages are a selection of Modernist followers, an odd collection that brings together Paul Rand, Herbert Matter, Neue Grafik, Quentin Fiore and Willy Fleckhaus’s work for Twen magazine. The randomness is a fitting end.

In spite of the admirable text in both German and English, and the excellent bibliography, the book’s usefulness is undermined by several deficiencies. For the English reader, captions to the illustrations, in German only, are of little value.

An explanation of the various printing methods and their limitations would have been a helpful addition: that the New Typography was essentially letterpress (hence it was reasonable for Tschichold to exclude as influences the large, lithographed Sachplakate); that size was restricted; that the scale of letterpress photoengravings was limited; that printing was rarely in more than one colour and black, and that photogravure was used mainly for high-quality reproduction of photographs for posters and popular magazines; and that full colour printing was slow to arrive in the 1930s. This might have given context to the wealth of images.

Professor Rössler’s publishers have managed to turn a good series of articles into a disappointing, over-illustrated book. In the same number of pages, with half the number of images, Professor Aynsley’s account is double the reward and tells a more complete story. There is room now for another book.

Richard Hollis, designer, writer, London

First published in Eye no. 99 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.