Spring 2018

Paper trail of a digital pioneer

Muriel Cooper

By David Reinfurt and Robert Wiesenberger<br> Foreword by Lisa Strausfeld, afterword by Nicholas Negroponte<br> Designed by Yasuyo Iguchi / MIT Press<br> MIT Press, $60, £49.95 (hardcover with slip-case, 240pp)<br>

The publication of Muriel Cooper will be a cause for celebration among many readers of these pages, its eponymous subject having long been regarded as an influential yet chronically undocumented figure within the field of graphic design. Up until now, anyone (outside the US) wishing to examine Cooper’s work will have had to rely on tantalising fragments scattered across various sites – articles, interviews, brief biographies, YouTube clips – without any authoritative source to draw on...

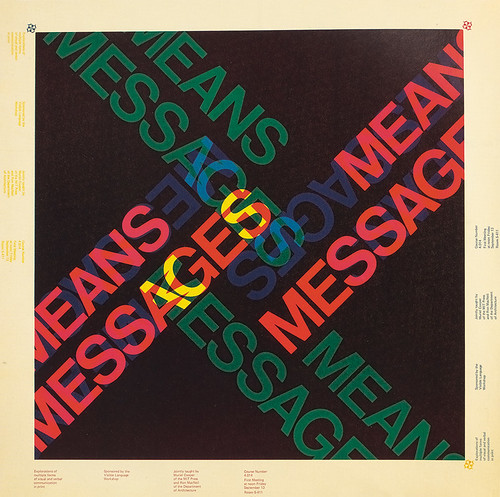

The well received 2014 retrospective ‘Messages and Means’ at Columbia University in New York, curated by authors David Reinfurt and Robert Wiesenberger, provided the first large display of Cooper’s work since her sudden death in 1994. Research for that exhibition provided the foundation for this book, which ought to become the definitive record of her achievements as a designer, teacher and researcher.

Those achievements were many and diverse. Cooper was employed by MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for more than four decades, during which time she oversaw the production of some 500 books while working at its Office of Publications and later as the first Design Director of MIT Press. She co-founded the Visible Language Workshop (VLW) where she developed an innovative approach to graphic design education that stressed the importance of iterative and real-time interaction with design and print processes, prefiguring the birth of desktop publishing in the 1980s. She became the first woman tenured at MIT’s interdisciplinary Media Lab, working alongside such luminaries as Marvin Minsky, Seymour Papert and Nicholas Negroponte. As Cooper’s career progressed, she began to produce less print-based graphic design and directed her attention toward technological research, exploring, through collaboration with colleagues and students, the computer’s potential to develop non-linear means of displaying and interacting with information.

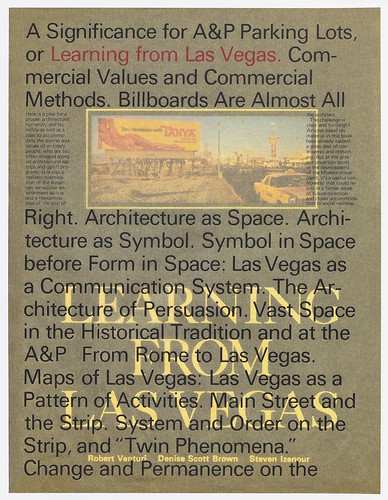

Cover for Learning from Las Vegas, 1972, by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour. Design: Muriel Cooper.

Muriel Cooper is divided between the primary text sections, featuring an extensively researched essay by each of the authors, and an image portfolio covering the themes of design, education and research. Lisa Strausfeld’s foreword and Negroponte’s afterword provide affecting tributes from the perspectives of student and friend respectively. Wiesenberger’s essay ‘Hard Copy (1954–1974)’, explores the first half of Cooper’s career at MIT, from early jobs designing flyers for summer courses, through her career as a book designer, and up until the establishment of the VLW. Reinfurt then picks up the trail for ‘Soft Copy (1974–1994)’ as the VLW’s incorporation within the newly founded Media Lab saw Cooper become ever more drawn toward the expansive potential of digital media. Much of the work discussed in these essays is reproduced generously in the image portfolio, though without further commentary. The text and image sections have been separated ‘to let each speak for itself’, though the screen-based works would have benefitted from some explanatory captions.

The division between print and digital is expressed more strongly by each essay’s title than in actuality, and one of the most fascinating conclusions to emerge from Reinfurt and Wiesenberger’s research is how this dichotomy never appeared to exist in Cooper’s mind. If one of the defining aspects of digital media is its feedback-driven mutability, then through the methods of working that she was developing early at the VLW, her use of analogue media was already ‘digital’ in spirit. The emergence of new media technologies in the 1980s do not appear here as the stark paradigm shift so often presented in design history, but rather as incremental steps (necessary to catch up with Cooper’s vision for how design could be produced) within a continuous progression. The prescience of her thinking is frequently striking – Reinfurt notes that by 1989, Cooper had already predicted ‘a near future where the information flow will be too fast for any designer to format it… [and where design] will become the task of creating templates and processes rather than bespoke pieces of communication.’

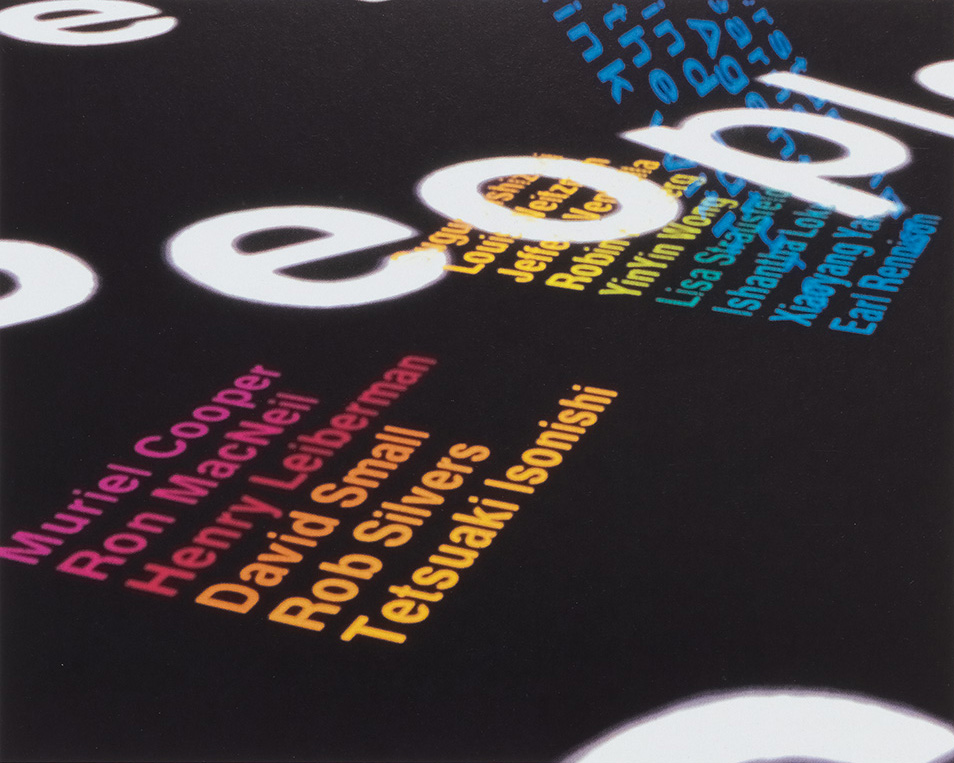

Muriel Cooper and Ron MacNeil’s poster for a course at MIT entitled ‘Messages and Means’, 1974.

Each author brings a complementary though distinct method of analysis. Wiesenberger constructs a slightly more traditional historical narrative than Reinfurt, whose contribution is often a reflective examination of the technologies that Cooper and her colleagues were immersed in at the Media Lab. A closing statement that situated the work within the broader landscape of graphic design of its time would have been welcome. The complex and apparently compromising nature of the Media Lab’s financial support system could have been expanded on further. Cooper and her students at the VLW were in an extraordinarily privileged position, with access to the era’s most advanced technology, often in prototype form, but completely reliant on corporate and, more uniquely, military sponsorship. Ultimately, while Muriel Cooper is an accomplished and scholarly study, it is also a highly self-contained one – an extremely pure work. Given its status as the first substantial statement on Cooper’s career, this is understandable, though future research might more actively frame her achievements through wider contexts within design and society.

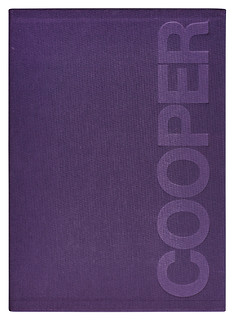

The book exhibits an impressive material presence and has been designed with skill and careful attention to detail, but it could be questioned whether its overt visual references to Cooper’s ‘hard-copy’ designs have been misjudged. Its size, slip-case, title design, typography and image layout all echo Cooper’s most well known work – the gigantic tome The Bauhaus – still in print. This size also recalls Cooper’s famously contentious design for Learning from Las Vegas (1972, republished in facsimile by MIT Press). Pastiche is far too strong a word, but given Cooper’s forward-looking attitude, a less historically oriented design might have produced a bolder, and thus more appropriate interpretation of her legacy. Nevertheless, Muriel Cooper should stimulate much interest in an individual whose singular importance has been so thoroughly demonstrated at last. Reinfurt and Wiesenberger’s request that the book function ‘not as an archive, but as a sourcebook for future production’ may yet be taken up by many.

Cover design: Yasuyo Iguchi / MIT Press, after Muriel Cooper.

John-Patrick Hartnett, designer and lecturer, London

First published in Eye no. 96 vol. 24, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 96 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.