Summer 2017

Paradise debunked

Design for the Corporate World 1950-1975

Edited by Wim de Wit<br> Design by Zoë Banther<br> Lund Humphries, £35<br>

The consensus among designers is that the middle of the last century was the golden age of corporate design: consideration and restraint produced work that never aged, while clients afforded designers complete creative freedom and trusted their judgement implicitly. It all sounds idyllic. So it is interesting to come across a book that suggests otherwise.

Design for the Corporate World 1950-1975 (edited by Wim de Wit, Lund Humphries, £35) attempts to investigate (in De Wit’s introductory words) ‘the tensions that threatened to undermine’ the fledgling relationship between business and design. It accompanies ‘Creativity on the Line’ at Stanford’s Cantor Centre for Visual Arts, which continues until 21 August 2017. It is split into two sections: a series of essays that position United States corporate design politically, socially and culturally; and an image catalogue of works included in the exhibition.

Designed by Zoë Bather, it explains how the design industry, looked at here as a multi-disciplinary whole, collaborated with corporate US following the Second World War, and how the two very different sectors struggled to understand one another. Some designers were plagued by doubt and frustrated by the lack of creativity this new partnership permitted. De Wit’s research into the International Design Conference at Aspen (IDCA) introduces readers to the history of the conference, which was founded in 1951 with the aim of acting as an interpreter between the newly intertwined business and design sectors; documented conversations from Aspen offer a candid insight into the concerns of the time. Greg Castillo’s essay ‘Establishment Modernism and its Discontents’ portrays mid-century design as wildly different to the fantasy we imagine: bitter in-fighting among designers, spats with environmental groups, and the government manipulation of design into a tool for psychological warfare during the Cold War. Louise Mozingo offers a slightly more positive view of corporate design by focusing on outcomes rather than relationships, giving an architectural backstory to the suburban corporate campuses that preceded those of Apple and Google. Steven McCarthy contributes ‘Design Education at Stanford’.

Design for the Corporate World 1950-1975 begins to deal with a set of ideas that feels refreshingly different to those in other publications on the same topic. You get the sense that many designers struggled with their involvement in postwar corporate US, often feeling morally and creatively compromised. So it is disappointing that the accompanying sequence of images is a predictable collection of examples from the period, including Olivetti, IBM and Pepsi Cola (whose NYC headquarters, designed in 1960 by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, is shown above). Such work reinforces the idea that it was an idyllic time to be a designer.

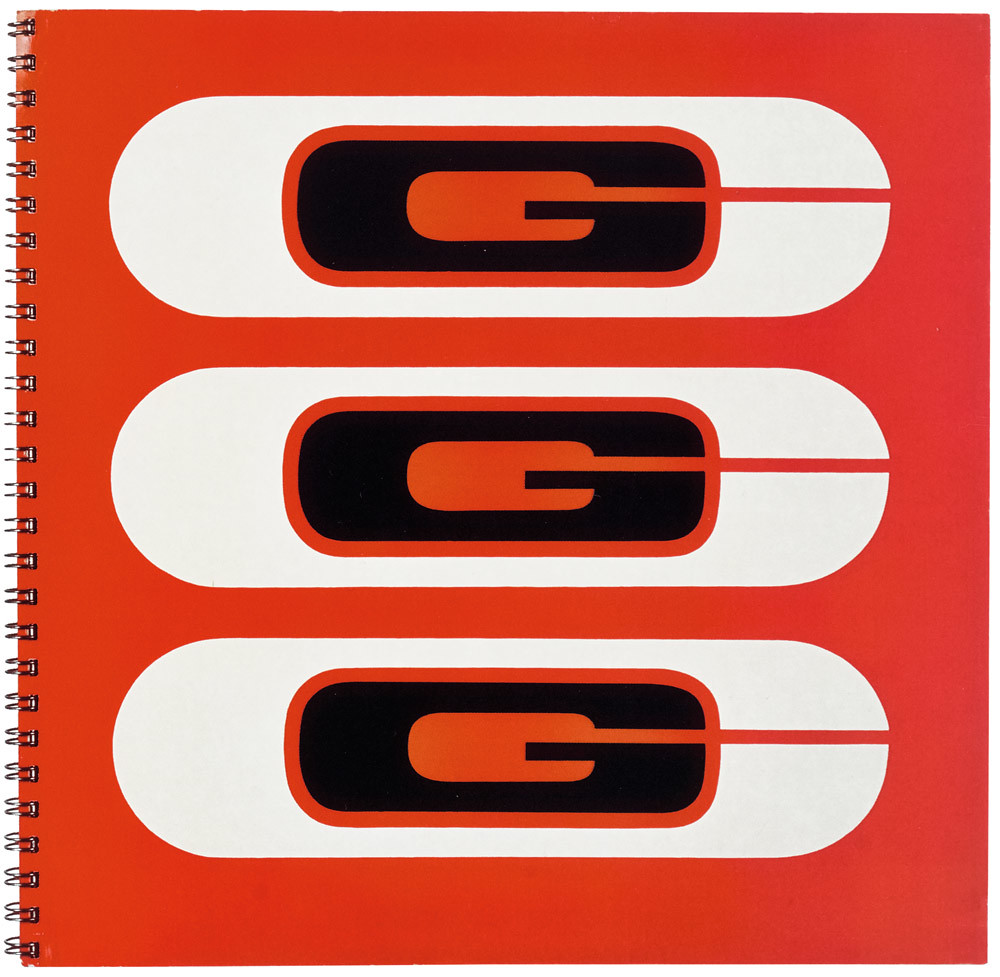

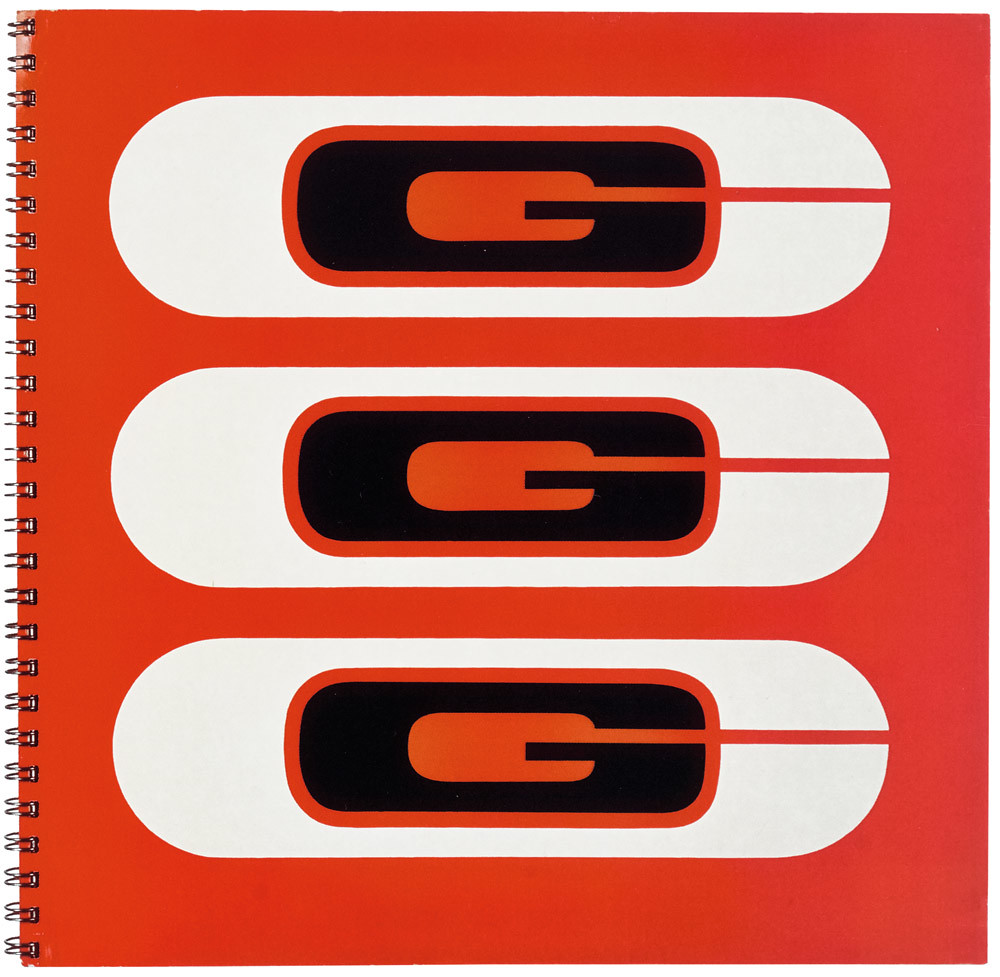

Designers’ inner conflict about their position as citizens who were sensitive to the changes of their time and who did not wish to be accused of ‘selling out to commerce’ feels pertinent in 2017. Clients such as IBM and Kodak and designers such as Paul Rand, Will Burtin and Lester Beall (whose 1958 style book for Connecticut General Insurance is shown below), were clearly exceptions that challenged the rule: companies and individuals who found a balance between creativity and commerce that suited both parties.

Most designers never found this sweet spot. What was their work like? Are the graphic designers who remained ‘servile’ to business, and whose work we never see, actually the ones we have most to learn from? The space between the new perspectives offered by the essays and the go-to examples of work implies a more interesting line of thought, but it is a position that the book never quite reaches.

If mid-century design has not aged, neither have the discussions that surround commercial practice. In 50 years, they have still not resolved themselves as designers once hoped. Design for the Corporate World 1950–1975 might not get us any closer to a resolution, but its texts cut through the nostalgia enough to offer a decent starting-point.

Design for the Corporate World 1950-1975 (Lund Humphries, £35), edited by Wim de Wit. Designed by Zoë Banther.

Hannah Ellis, designer, educator, London

First published in Eye no. 94 vol. 24, 2017

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 94 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.