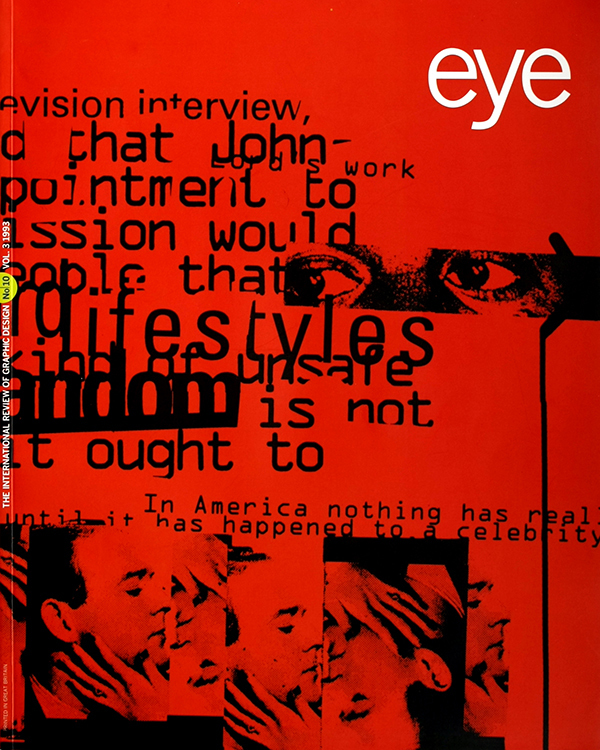

Autumn 1993

Playing the game by Rand’s rules

Design, Form, and Chaos

Paul Rand, Yale University Press, £35, $45Most American graphic designers become irrelevant long before they reach Paul Rand’s age. No doubt he confounded many onlookers who had him slated for dormant eminence-grisehood in the mid-1980s by responding with the one-two punch of the publication of A Designer’s Art in 1985 (complete with a page one notice in the New York Times Book Review) and, a year later, the design of the NeXT logo for Steve Jobs, along with a notorious reference to the logo’s 0,000 price tag). Since then, Rand has ruled virtually unchallenged as the King of American Graphic Design.

Rand, or perhaps the mythology that has been attached to him, has also served as the dominant role model for how many of us think design should be practised in the US. The legendary relationship between Rand and IBM’s Thomas Watson Jr, for instance, has served to define what almost all designers hold as a prerequisite of “getting good work done” – that is, Svengali-like access to a chief executive office genetically predisposed to like “good design”. Whether or not the Rand-Watson relationship is a plausible model for corporate practice is meaningless in the face of our vast collective fantasy about it. In the same way, many commonly held beliefs about how to do design reflect Rand’s example: the idea that the smaller the office the better, that a logo is the crucial starting point in corporate identity, that the formal interpretation of visual ideas is the designer’s primary mission.

It was indeed from Olympus, then, that Rand unleashed a thunderbolt in the form of “From Cassandra to Chaos”, an essay that appeared last year in the AIGA Journal. Just when the forces of “deconstructivism” seemed about to overturn the verities of Modernism, Rand put his foot down. Much contemporary graphic design, he said, is degrading the world as we know it, “no less than drugs or pollution”. No names, of course, but one could easily identify the culprits Rand had in mind from his litany of their modi operandi: “squiggles, pixles, doodles” (Grieman et al.), “corny woodcuts on moody browns and russets” (Duffy, Anderson, et al.), indecipherable, zany typography” (Valicenti et al.), “peach, pea green, and lavender” (anyone from California named Michael, et al.), even “tiny coloured photos surrounded by acres of white space” (which obviously only sounds harmless).

Predictability, the essay was received with almost tearful relief in some quarters, and with exasperation in others. Insiders read Rand’s statement that “To make the classroom a perpetual forum for political and social issues, for instance, is wrong; and to see aesthetics as sociology is grossly misleading” as a not-so-thinly veiled repudiation of Sheila de Bretteville’s newly minted regime at Yale, Rand’s distaste for which, it was said, had led him to resign his teaching position there. It was also said that the essay was only a hint of what was to come in Rand’s new book, Design, Form, and Chaos.

The book, somewhat disappointingly, is less a manifesto than an illustrated anthology not unlike its predecessors. The title (which is variously punctuated throughout, appearing here with no commas, there with two) is nowhere explained, unless it serves to emphasise the important of Rand obviously places on “From Cassandra to Chaos”, which closes the book. About half the book consists of essays, all but one previously published, which are illustrated, like those in A Designer’s Art, by the author’s own work. Subjects include Erik Gill’s An Essay on Typography (which he feels is great but the original jacket was better), computers (OK, but not character-building like using a ruling pen), design’s role in the business community (not so hot, with much crowd-pleasing condemnation of market research and more longing for genetically predisposed CEOs). But make no mistake: even someone who disagreed with Rand’s premises would admit that, nearly without exception, the essays are thoughtful, well reasoned and gracefully written. For the undecided, a veritable army of names is enlisted to press the cause, including Arp, Leonardo, Kant, Le Corbusier, Kandinsky, Léger, Malevich, Malraux, Rembrandt, Skinner, Schwitters, Tschichold and Mies van der Rohe, not to mention Abraham Lincoln and Alistair Cooke.

The book’s real appeal, though, probably won’t be the essays, but the nearly 100 pages Rand devotes to reprinting brochures and about six of his logos, including IBM, IDEO and NeXT. These were originally created as presentations of identity projects commissioned by these companies, and each is a model of step-by-step clarity and elegance, with no small appeal for the voyeurs among us.

Equally striking, especially in the context of the surrounding essays, is the obsession with minute formal issues that recur throughout these presentations. Nearly every example is accompanied by text that reduces the design process to the lengthy examination of the juxtaposition of round letters and square letters, of too many vertical letters in a row, of adjacent round letters that jumble together, of letters that cluster and separate from the whole. A valid part of the design process to be sure, but oddly emphasised by a designer who quotes approvingly Philip Kotler’s claim that “design is a potent strategy tool that companies can use to gain a sustainable competitive advantage.” One wonders how sceptical CEOs react when confronted by the mysterious God in these endless details; probably as they do on Sunday mornings, with the proper mixture of awe and reverence, and in the comfort that on Monday it’s back to the real world of business as usual. Rand complains that most business people “see the designer as a set of hands – a supplier – not as a strategic part of business.” Can they be blamed?

For when all is sad and done, Paul Rand sees the design process not as strategy but as an intuitive search for an absolute ideal: “unity, harmony, grace and rhythm “. Content is important, in so far as it provides a starting point for the formal ends that “ultimately distinguish art from non-art, good design from bad design”. In this way, he is scarcely different from the culprits he criticises so passionately.

Rand himself is aware of this contradiction, but doesn’t seem to grasp its full implications. “To poke fun at form or formalism is to poke fun at … the philosophy called aesthetics. Ironically, it also belittles trendy design, since the devices that characterize this style of ‘decoration’ is primarily formal”. Having banished social and political issues to the sidelines, the game is reduced to the Good Formalists against the Bad Formalists. There seems to be more than enough irony here to go around.

Rand rails against the state of graphic design today, leaving unmentioned the fact that this young profession has been invented very much in his own image. He taught many of today’s most influential practitioners; he taught the teachers of countless others. His book goes out into a world where half of us are single-mindedly pursuing our own essentially formal notions of beauty and anti-beauty and the other half are earnestly trying to solve someone’s business problems with an attractive logo. To Rand’s everlasting dismay, all of us keep playing the game by the rules he helped invent.

Certainly there’s no denying that Paul Rand is a living legend. Nonetheless, it is more than a little sad that of the dozens of names invoked in Design, Form, and Chaos, the only living designer mentioned is the author. Perhaps the profession of graphic design is truly in the state of crisis Rand claims. If our respected elders care as much as they say they do, the least one could hope for is a bit less crankiness and a bit more generosity of spirit.

First published in Eye no. 10 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.