Winter 2005

Political imagery re-examined

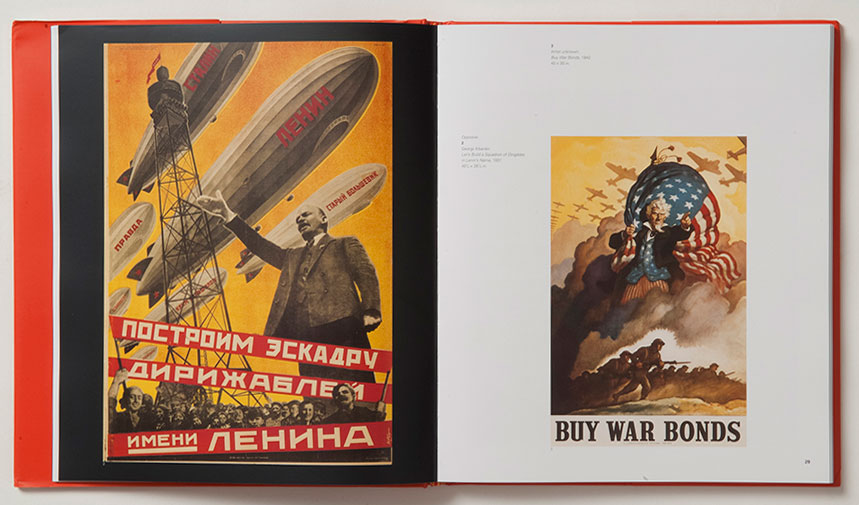

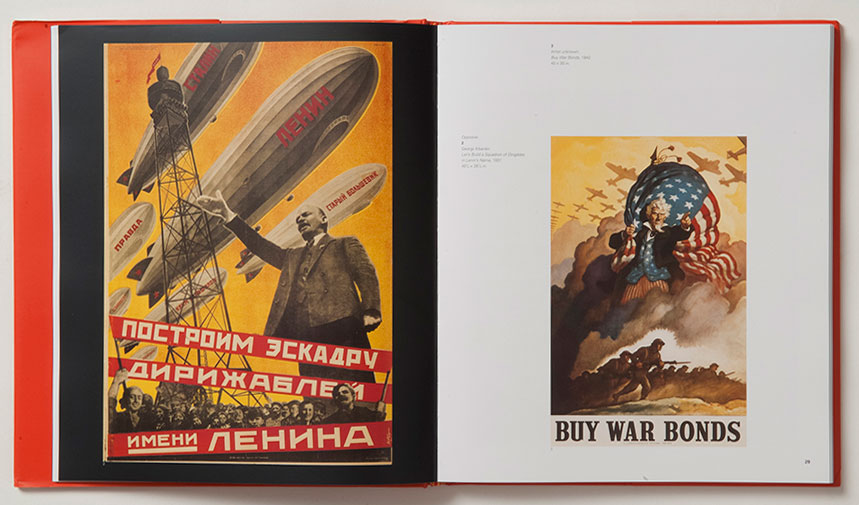

Revolutionary Tides: The Art of the Political Poster 1914-1989

By Jeffrey T. Schnapp<br> Skira in association with The Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, $45<br>

One challenge of design and art historians today is how to analyse familiar material, like political posters, through unique lenses. ‘Whereas the conventional approach to poster art emphasises classifications based on artist, period, political ideology, and nationality,’ writes Jeffrey T. Schnapp, director of Stanford University’s Humanities Laboratory, ‘Revolutionary Tides is instead concerned with the emergence of a common graphic vernacular for depicting multitudes as political actors on a worldwide scale and in a multiplicity of only loosely interconnected artistic, political, and historical settings.’

In fact, this book – a catalogue of 120 posters from the US brought together in an exhibition held at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University and the Wolfsonian Museum at Florida International University – is intended as a ‘macrohistory’ of the political poster, focusing on how mass movements played decisive roles in effecting social change. The exhibition is one segment of the ‘Crowds project’, which considers how twentieth-century life was informed by the rise of the twentieth-century notion of the ‘mass’.

In Masses and Man: Nationalist and Fascist Perceptions of Reality (Howard Fertig, 1980), the historian George L. Mosse examines how mass obedience developed in iron-fisted states through persuasive media that used, among other bludgeoning tools, graphic signs and symbols to squeeze individual thought into a behavioural machine. Graphics have long played a role in both stirring the populace and keeping them in line. Forging a potentially unruly mass into an obedient entity using covert and overt graphic depictions – either through deception or truth – is a key challenge for any propagandist and not unique to dictatorships. As the posters in Revolutionary Tides attest, democracies used the same vernacular to achieve their goals: a sobering and disturbing thought. It is also the most significant part of this valuable book.

At first glance, however, the book’s value is questionable since it appears to cover very familiar ground. Included are a predictable number of classic political posters by John Heartfield, Gustav Klucis, Xanti Schawinsky and Lester Beall. There are also as many anonymous images – some common others obscure (like Bohumil Stepan’s startlingly simple West Czechoslovak Communists Will Donate Half a Million of Work Hours to the Republic). Still, a cloud of cliché hangs over the pages given the many recurring depictions and mutual colour palettes shared by these missives. But this repetition is, of course, the point.

In Genius Moves, a book I authored with Mirko Ilic, we defined graphic design icons according to 100 motifs that illustrate how recurring visual images and ideas influence in many other iconic designs. Using a similar methodology Revolutionary Tides fits political posters into conceptual ‘clusters’ to show how common traits and tropes – such as clenched fists, handshakes, pointing fingers, waving flags, silhouetted heads and marching men and women – are standard idioms used to trigger programmed responses. In ‘Anatomies of the Multitude’, people with clenched fists represent the power of the body politic; in ‘Mass Leaders and Mass Deceivers’ images of Marx, FDR, Mussolini and Hitler are superimposed upon the faceless faces who dutifully follow them, while ‘The Man of the Crowd’ category shows images of heroic individuals who compose the crowd and, in turn, represent the larger body.

The virtue of this book is that by grouping these elements together, it proves that very little is new in political imagery – only the faces change, while even the flags and doctrines stay the same. Odd as it may seem, for me the epiphany in this book is a small photo in the ‘Annotated Entries’ section of Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi’s plaster Study for Statue of Liberty (early 1870s) showing an early stage of the robed icon with her arm held high. To see this in the context of all the other straightened arms shows how political Liberty is and how influential it was.

But one last quibble. The title suggests a different book than this one. Many of the posters are designed not to revolt but to enforce the status quo. In Russia, Germany, Italy and even the United States the revolutions had been fought and many of the political posters selected here are simply a means of insuring against reaction.

Steven Heller, design writer, New York

First published in Eye no. 58 vol. 15, 2005

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.