Autumn 2001

Political punch

Nasty Tales: Sex, Drugs, Rock ‘n’ Roll and Violence in the British Underground

David Huxley<br>Critical Vision, £13.95<br>The refreshing thing about David Huxley’s heavily illustrated history of British underground comics is the attention to political context. This isn’t a book just about how extraordinary the art is (though there’s a great deal to savour here) or how amusing the gags are, but why particular art styles were chosen and why those gags were relevant in the first place.

This is not to say that many of the comics were overtly political – as Huxley points out, ‘At one level it may seem strange that there are few comics which deal very directly with politics, especially during the period 1966-73 when the Vietnam war and “new politics” dominated counter-cultural thinking.’ Yet, as Huxley goes on to explain, the key problem is how one defines ‘political’, and it’s more sensible to argue that every time a comic’s character has wild sex or smokes a huge joint, a political point is being made. Thus, in a broader sense the comics were both the makers and transmitters of the counter-cultural ‘message’.

This being so, they have a power that is lacking in mainstream commercial comics. The American underground was a major influence – especially R. Crumb - but the British variant had a flavour all its own. Of the examples pictured, my favourites are Mike Weller’s magnificent ‘Tea Break’, from Cozmic Comics (1972), and Ray Lowry’s ‘True Meat Tales’ from Cyclops (1970). The former depicts the problems British hippies encountered when trying to get the working class interested in radical politics: a comment on the fact that in 1968, when the French students and workers were forming an alliance and attempting a revolution in Paris, British dockers were marching in favour of Enoch Powell (as one frustrated long-hair says in the strip: ‘Fuck off, grandad! Keep yer chains!’). The latter strip is a mixture of psychedelic collage and loose pen-work inspired by Tomi Ungerer, and has more inventiveness than Syd Barrett on an acid bender.

There are also hints of how weird the comics could get: this was an era, after all, when there were no rules. Antonio Ghura, usually one of the most amusing of the British crop, completely came off the rails with his ‘I Loved a Sex Fiend!’ from Truly Amazing Love Stories (1983), wherein a character (‘Paul Rutcliffe’) with more than a passing resemblance to the Yorkshire Ripper engages in an explicit rape that lasts for four pages. Ghura later admitted that he’d drawn the strip when he wasn’t feeling ‘right in the head’.

The book isn’t totally successful. Although the years 1966-76 – the period of the first flowering of the underground – are covered in admirable detail, things come a little unstuck regarding the remainder of the chosen time-frame (to 1982). Important names are ignored (there’s no mention of Savage Pencil) and the start date of Viz is given variously as 1979, 1980 and 1982. But these are minor quibbles, and the generally excellent Nasty Tales remains, to borrow one comic’s strapline, a journey into delirium.

Roger Sabin, writer, author of Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels (Phaidon), London

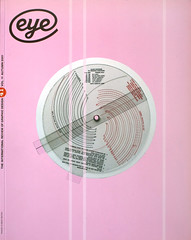

First published in Eye no. 41 vol. 11, 2001

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.