Summer 2012

Psychedelic tract

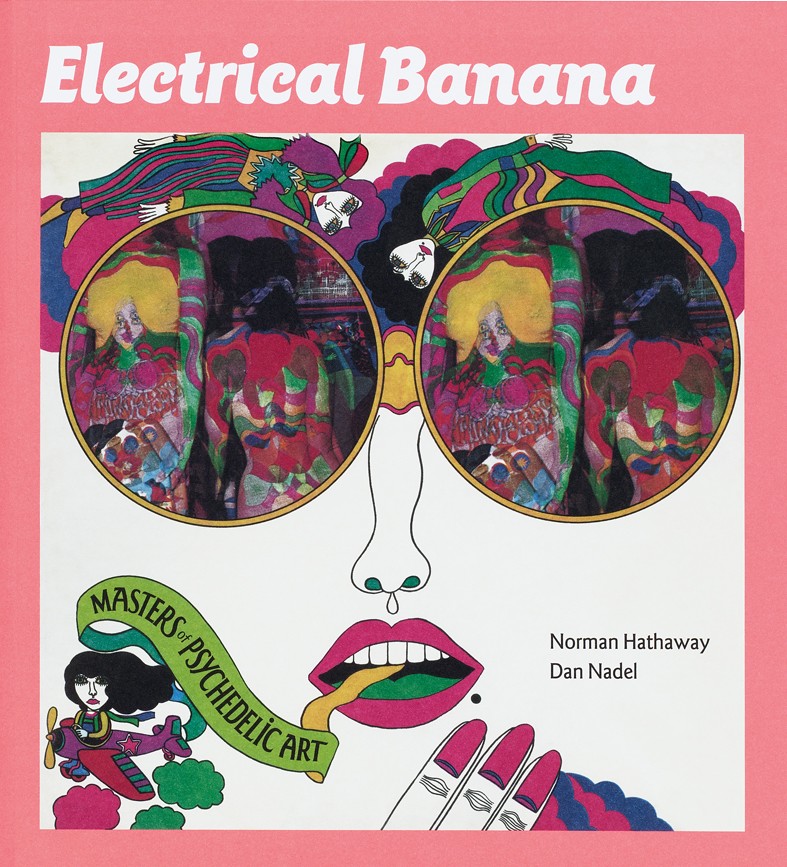

Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art

By Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel Damiani £27, $39.95 Reviewed by John L. Walters

The era of psychedelic art – from the mid 1960s to the very early 70s – was so short that it is often overlooked, misunderstood or dismissed as a curious, slightly embarrassing mix of American eclecticism and stoned English eccentricity. Here Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel make a passionate argument against such negative views by selecting a mini-canon of seven non-American artists who played key roles in psychedelic visual culture: Heinz Edelmann, Mati Klarwein, Tadanori Yokoo, Keiichi Tanaami, Dudley Edwards, Martin Sharp and Marijke Koger (of the Fool). Two Germans, two Japanese, an Englishman, an Australian and a Dutchwoman.

Each is covered by a short biography, an interview and a generous selection of work, most of which is difficult to find elsewhere. It is a fascinating complement, a sort of ‘prequel’ to Hathaway’s Overspray, his lovingly compiled book about half-forgotten airbrush artists from the 1970s (see Roger Sabin’s review in Eye 71).

Edelmann (1934-2009) is the most reluctant psychedelicist, whose grumpy recollections of the chaos surrounding the making of the Beatles’ animated film Yellow Submarine are both funny and poignant: ‘They would hire anybody who could stand upright and hold a brush.’

The piano Dudley Edwards painted for Paul McCartney in 1967. Top: Cover design adapted from Keiichi Tanaami’s design for After Bathing at Baxter’s by Jefferson Airplane.

The Beatles figure strongly. Edwards (b. 1944), Electrical Banana’s sole Englishman, was hired to paint vivid, hard-edged designs for Paul McCartney’s piano, and a mural for Ringo Starr. Koger (b. 1943) painted a piano for John Lennon and a fireplace for George Harrison, plus the wavy red inner bag for the vinyl edition of Sgt. Pepper’s.

Koger’s four-piece collective, the Fool, are rescued from pop’s footnotes by a sharp and fascinating interview, accompanied by a small reproduction of proto-psychedelic work from her teenage years. For example: ‘Q: But it seems like you were doing this type of work when you were fifteen, way before drugs and stuff. A: No, I was doing drugs back then.’

All the interviews are full of nuggets – even the bizarre 1983 text in which Klarwein (1932-2002) interviews himself. Yokoo (b. 1936) talks about the close collaborations that enabled his hallucinatory use of colour separations. Tanaami (b. 1932) describes the impact that American counter-culture made upon him on his first visit in 1968. ‘But really,’ he continues, ‘my psychedelic work comes more from my memories of my childhood [during the Second World War].’

Sharp (the Australian) is possibly the best known poster artist here (see Eye 42), and his recollections are informative and moving, paying tribute to a lost Chelsea arts scene that included Eric Clapton, Nigel Waymouth and David Litvinoff and talking about his murals for the film Performance, often viewed as a violent coda to the psychedelic era.

I would describe these interviews as highly readable were they not set in an array of coloured, often fluorescent inks. This, together with the thick shiny paper on which it is printed makes Electrical Banana a drag to read and (pause, inhale) way too heavy, man.

First published in Eye no. 83 vol. 21 2012

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.