Spring 2019

Rules of engagement

Theory of Type Design

By Gerard Unger. Edited by Christopher Burke. Designed by Hansje van Halem. nai010, €34.95, £38.75

Back in 2005, I wrote ‘In Search of a Comprehensive Type Design Theory’, a somewhat tongue-in-cheek article in which I argued that ‘Type design [...] seems to resist attempts to establish an encompassing theory by its very nature. Type design is not an intellectual activity, but relies on a gesture of the person and his ability to express it formally’. I had been teaching type design for a number of years, and the article was a reaction to student requests to reveal the ultimate truths about type, its fundamental rules and principles. Type design is a series of personal discoveries built upon the collective memory of the profession. It is easy to acquire basic skills, but almost impossible to distil the vast diversity of type into a unified theory of type design.

That’s why I was eager to read Gerard Unger’s Theory of Type Design. Unger (1942-2018), the venerable Dutch type designer, digital type pioneer and eyewitness to the technological shifts of the past five decades, was not only a professor of type design, but also a prolific writer and researcher.

In 25 concise chapters, a length perhaps too short to allow in-depth exploration of the subject, Theory of Type Design provides a framework and terminology for the components of type design and typography. It discusses the inner workings of text, its structure, pattern, texture, consistency (or deliberate inconsistency), coherence and rhythm. The book focuses, more than on strokes or letter-shapes, on the organisation of text, on aspects of layout that affect its clarity, especially when the reading process is nearly automatic, when shapes, words and sentences flow directly into the reader’s brain, aided by the conventions of typesetting.

In his writing, Unger was more interested in investigating the discipline than providing answers. Often there are no answers; for example, a formula for the perfect relationship between negative and positive forms (text fitting or spacing) is impossible to derive, as letter shapes are too diverse to be governed by simplified rules. He urges designers to formulate their own research questions rather than wait for accepted research results, to reach out to scientists and to work together with them. The chapter on legibility consists mainly of questions: do the fine details of type matter in small sizes when text dissolves into a texture? Does high x-height in a typeface aid legibility? Are serif typefaces more legible than sans?

Theory of Type Design provides thoughtful insights from a master practitioner, but the book does not reveal any ready-made theories or methods for making typefaces more effective. It is not for type design students hungry for rules, but a resource for an advanced professional interested in discovering more about the complexity of the craft.

All of which raises the question of whether this book does indeed present the comprehensive theory of type design that the title promises. If we follow the generally accepted understanding that the word ‘theory’ means a formal system of rules supported by evidence, or a set of hypotheses that can be proven true or false, or basic principles leading to a generalised system of type design creation, then the answer is ‘no’, and the title of the book is inaccurate. But Unger seems to use the word ‘theory’ to mean

a scholarly foundation for reflecting on and discussing his practice-based research, and in this he succeeds deftly.

While Unger designed his previous books himself, for this one he engaged his former student Hansje van Halem (see ‘Strategy of excess’, pp.42-49 ). This choice may seem surprising, since she is known less for functional typography and more for creating vibrant, hypnotic patterns on the boundaries between type and image. However, perhaps Unger chose her precisely to demonstrate the rich possibilities that type design and typography offer. The two worked closely together, and the book combines Van Halem’s experimental lettering and Unger’s typefaces. It also features decorative endpapers that Van Halem produced as a side project with printer Jan de Jong. Van Halem’s page design puts all the illustrations at the end of each chapter, which makes the reading somewhat less continuous, as one has to flip back and forth between the text and the examples to which it refers. Physically, the format of the book allows easy handling and comfortable reading, and the book binding (by Bindery Van Waarden) is up to the standards of the best book production in the Netherlands.

Theory of Type Design encourages us to explore. Gerard Unger’s research, writing and practical work have established him firmly in the history of the profession, along with Eric Gill, Stanley Morison, Adrian Frutiger or Gerrit Noordzij, practitioners who sought to elevate the level of discussion in type design.

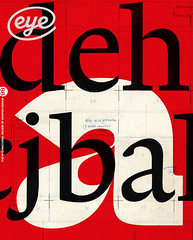

Cover with lettering by Hansje van Halem (see ‘Strategy of excess’, Eye 98).

Top. Spread from Theory of Type Design, designed by Van Halem.

Peter Biľak, designer, Netherlands

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.