Autumn 2011

Testament to tenacity

Windows on the War: Soviet TASS Posters at Home and Abroad, 1941-1945

Edited by Peter Kort Zegers and Douglas W. Druick<br />Designed by Studio Blue<br />Yale University Press / Art Institute of Chicago, $65, £45Hitler knew that without the Soviet Union threatening his flank, he could march on Eastern Europe with impunity. Stalin knew that without Hitler at his front door, he could help himself to some of the spoils of Nazi aggression. Hence in 1939, the ten-year Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact was signed. Barely two years later, in 1941, Hitler unilaterally broke the pact with the pre-dawn invasion of the USSR. Stalin was forced into an alliance with the United States, and, if not for this change of strategy, it is quite possible the war might have ended in a stalemate, with the Nazis in control of much of Europe. Instead, fearing for their existence, the Soviets threw everything they had against the Germans, including relentless barrages of printed propaganda – enough, in fact, to fill 400-plus pages of a book.

Windows on the War is that book, or, rather, an extensively documented and beautifully designed catalogue of a recent exhibition organised by the Art Institute of Chicago. The catalogue is not just a record of an installation, it is the permanent testament to Soviet tenacity in the visual realm. Say what you will about the turgidity of Socialist Realism, this post-avant-garde period of Soviet propaganda is creative and expressive. Effective propaganda may foster various emotions – from nationalist pride to atavistic hatred – but it also must convince the receiver to embrace the cause.

When bombs are falling it is hard not to hate, yet ‘defeatism’ is always an internal enemy, and propaganda must fight against it. Somehow, as shown so effectively in this volume and exhibition, Soviet artists were able to rise to the occasion on a virtually daily basis. And although the majority of examples are totally new to me (as they were to the curators who found them rolled up in tubes hidden from view for decades), a few have made it into the history books. Boris Efimov’s ‘Joe Rat’, a caricature of propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels as a shrieking doppleganger for Mickey Mouse, part of a series titled ‘The Berlin Gang of Bandits’, is one of the most widely reproduced cartoon images of the war.

TASS (Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union) produced hundreds of numbered ‘Window’ posters during the war, direct descendents of the preceding ROSTA (Russian Telegraph Agency) Windows (so-named because they were routinely displayed in storefront windows left empty by the Revolution). ‘While virtually unknown outside the former Soviet Union’ write Druick and Zegers, ‘TASS posters are exceptional even within its borders and in the context of its history of agitational propaganda.’

The book and exhibition make the convincing case that ‘TASS Windows stand outside mainstream modern poster history – from which they have been largely excluded’ and through a series of essays by various contributors chart both the niche and historical continuum where these images reside. In addition to discussions about stencil as a medium that pre-dates printmaking, and surveys of the ROSTA Windows illustrated by Mikhail Cheremnykh and written by Vladimir Mayakovsky, and civil war posters by Dimitri Moor, the book takes great pains to trace the origins of the styles used to capture Soviet hearts and minds.

I could stare at these disturbing images for hours, if only to decipher the hidden messages the artists might have included. But I was most absorbed by one profusely illustrated chapter. ‘Paper Ambassadors’ by Jill Bugajski could have been a book unto itself on the history of Second World War posters. While this is a subject well travelled by social and design historians, Bugajski expertly weaves together all the important discussions, including a surprising section on ‘MoMA’s Call to Arms’ on the young museum’s ill-fated plans for a ‘spectacular artistic intervention in the war debate’ that would have been ‘the largest anti-Fascism exhibition held in the United States’. MoMA did, however launch a ‘National Defense Poster Competition.’

There are other historical tangents in this catalogue, but the main event, the TASS Windows, are breathtaking – and at times terrifying. The large scale and heft of the book provides authority, but the manner in which Studio Blue has balanced the images and text allows readers many entry-points into the work.

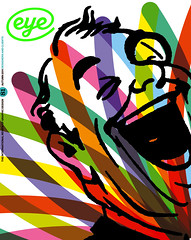

First published in Eye no. 81 vol. 21 2011

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.