Winter 1993

The boy’s book of Pentagram

Bob Gill

John McConnell

Colin Forbes

David Hillman

Paula Scher

Theo Crosby

Graphic design

Reviews

Pentagram: The Compendium

Edited by David Gibbs, Phaidon Press, £39.95Pentagram are masters of self-promotion. ‘Books win friends,’ says Theo Crosby, ‘and buying friendship is perhaps the most economical investment one can make.’ Which puts other design companies’ PR and marketing people in their place.

‘Compendium’ suggests a box of tricks and Pentagram: The Compendium – imposingly boxed in a matt black slipcase – is the partnership’s biggest array of tricks to date. The book is part philosophy, part reminiscence, part text book – and not least, part corporate brochure.

The underlying philosophy of Pentagram: The Compendium is that design is a serious business. But while the book says a lot, it gives little away. During the 1980s, when every designer in London seemed to want to become a public company, I asked partner John McConnell about Pentagram’s plans. ‘Why give up control to a bunch of people who probably have no interest in design?’ he said. ‘Shareholders measure success in terms of financial dividends and corporate growth. Designers tend to look for improved quality of work. And as many design companies have demonstrated, growing by acquisition, by bolting on parts, can produce some uncontrollable monsters.’

Design companies reflect the interests of their owners. Wolff Olins’ specialisation in corporate identity reflects a business consultancy background, while Michael Peters’ commercial interests led the company to raise the standards of brand packaging in the 1970s. Pentagram’s skills are more general – their clients, since the early days, have included multinational corporations, under-funded arts organisations and interesting individuals. One of their achievements has been to make seemingly deadpan companies appear fun-loving people. It is assumed that such organisations pay well too, which enables Pentagram to work for less well-heeled clients whose projects go on to win recognition and prizes, and who provide a different level of stimulation.

Since the original five designers set up Pentagram in 1972, the partnership has grown to 17 and spread its network to New York and San Francisco. But the group’s approach to growth has been by stealth rather than by developing a traditional corporate pyramid. Pentagram is a federation of small overlapping companies, each run by a partner who has gained recognition in his or her own field, whether graphics, architecture or product design. This principle allows new partners to be added and others to leave without damaging the overall structure.

A pre-Pentagram leaver was Bob Gill. When Theo Crosby arrived in 1965, he was involved in a long-term project. Gill asked him when the first buildings would go up. ‘About 1973,’ said Crosby. ‘That’s a long time to wait for a proof,’ said Gill, and left.

Other partners have come and gone, the most recent arrival being David Pocknell, while industrial designer Daniel Weil joined too late for more than a mention in this book. The arrival of Peter Saville in 1990 seemed a surprising move to some, since his background in pop culture and style appeared alien to Pentagram’s more hard-nosed philosophy. Whether it was an attempt to introduce a different design direction, or more likely to include the best designers, whatever their background, is unclear. Speculation over his leaving was probably greater. Fitting into a new environment no doubt causes problems, but acceptance of a way of working that has evolved over a long period can create even greater pressures.

As Pentagram has become part of the design establishment, it has acted as a breeding ground for new design groups. Non-partners have gone on to form companies that have become the desirable ‘hot-shop’ offices for students’ first jobs that CFF and Pentagram were in the 1960s and 1970s.

As well as giving a history of the development of Pentagram, The Compendium contains many exemplary texts, not least David Hillman’s review of the Guardian redesign and partners McConnell, Forbes, and Grange’s examination of design consultancy. McConnell views the way most designers use the term consultant as a misuse: ‘consultancy means advising a client on how to go about using design and assessing whether the results are right or wrong; it does not mean advising and doing it yourself. You can’t play the role honestly from two sides of the table.’

Alan Fletcher’s contribution includes a collection of non-designers’ views on design and a look at the development of writing from pictograms through ideograms, photograms and petrograms, and logograms. All of which suggest likely starting points for the company name, though in fact, after rejecting ideas such as Big D (Building Industrial and Graphic Design) as too jokey, Pentagram was found in a book about witchcraft.

Ralph Caplan says in his foreword that the enjoyment of design is intrinsic to Pentagram. Wit, rather than humour, plays a large part in their work. McConnell’s piece on making faces demonstrates the partners’ enjoyment in discovering human form in found objects and unlikely juxtapositions. In his introduction to a chapter entitled ‘The Figurative Wit’, Woody Pirtle explains that by linking disparate themes ‘an analogy may concisely present an idea which otherwise would take many words to explain’. The pun, metaphor, cliché and analogy are defined in visual terms in the introduction, but not just by graphic solutions: also illustrated is a bathroom sink counter designed by James Biber in the shape of the state of Montana for a child of that name.

Many of the forms of visual humour indulged in by Pentagram have become clichés. While the London partners have tended to alter or enlarge a meaning by making a simple adjustment – as a hangover, one imagines, from the early days of being required to make something out of nothing on a tight budget – the American partners go in for wit in a big, no-expense-spared way. Paula Scher contributes a chapter on the dangerous area of parody and the Zeitgeist. Most designers have the view that if you can see it, touch it or hear it, it’s fair game. But at what point does it become a rip-off? If the objective is to say something new about an existing image, then perhaps if everybody understands the joke, it is parody, whereas if nobody gets it, it is plagiarism.

As well as Christmas booklets which take the form of light-hearted entertainment and Feedback, which demonstrates the designer’s interest in odd places and sometimes odder food, the partners have produced several books about their work. Their first book, Pentagram: The Work of Five Designers sold – to their surprise – 10,000 copies in the US. Their second, Living by Design, sold 25,000. The subject matter of their most regular and durable publication, Pentagram Papers, varies from architectural monographs to collections of skeletons and American flags. The original intention was to pass on information, but as the partners have discovered, being associated with authors who are academics and intellectuals has put them in a very positive commercial position. As they realised long ago, words add weight.

Brian Webb, graphic designer, London

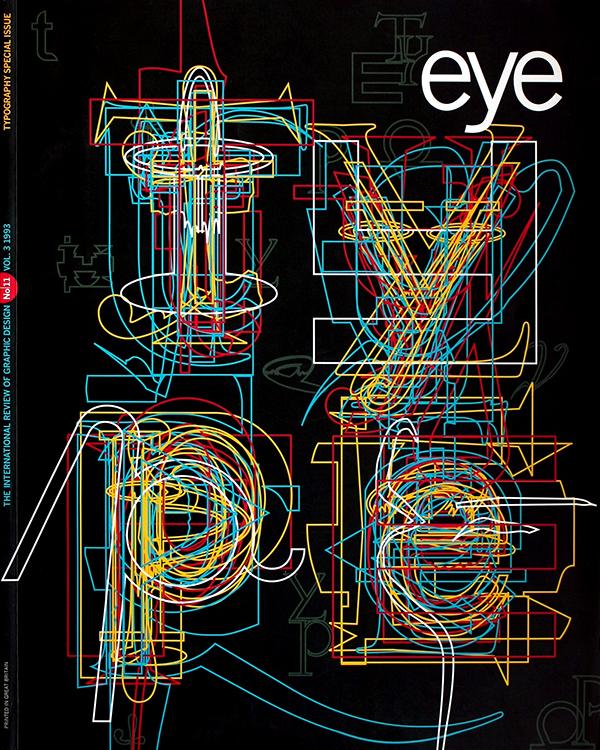

First published in Eye no. 11 vol. 3 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.