Spring 2002

The designer as programmer

Karl Gerstner: Review of 5x10 Years of Graphic Design etc.

Edited by Manfred Kröplien<br>Hatje Cantz, £45<br>‘Swiss’ is still a style. In the crudest terms, the style was, and is, Helvetica, Univers and grid systems – the style of Zurich and Basel in the 1960s. The founding fathers of Modernist graphic design in Zurich, Max Bill, R. P. Lohse and Müller-Brockmann, have had their careers zealously recorded. As for Basel, Emil Ruder and Armin Hofmann have memorialised their own achievements and attitudes, and at last Karl Gerstner takes his unfilled place in the history.

This book reminds us of the huge influence of both his work and his books: nobody matched Gerstner’s originality as a typographer nor his daring as an advertising designer, and as a theorist he was for decades the most coherent writer on graphics. But in ‘a kind of autobiography’, as he calls the book, Gerstner cannot easily say how great, original and influential he is.

In 1972 the Swiss monthly Typographische Monatsblätter published a special issue on Gerstner, the fifth in the series Pioneers of 20th-Century Typography. Gerstner’s importance was in the three ways he had built on earlier work. First, he had developed the idea of a flexible grid – the central theme of Gerstner’s thinking was on computational systems, which he described as ‘programmes’. Second, he was a pioneer of unjustified, ranged-left setting for text. Third, he had extended ‘functional’ into ‘integral’ typography, where the message and its form are inseparable and interdependent – idea, text and typographical presentation are one. The book presents the five decades of his working life, with an introduction to each section (text on white pages) and a commentary on each job (reproduced in white panels on warm grey). Each decade is preceded by an essay There are also essays (on cold, blue-grey pages) on art and design, on visual language, on logos and labels, on the job of the art director, and ‘Good Design: What Is It?’

Born in Basel in 1930, Gerstner did a foundation year at the Basel School of Arts and Crafts, and was then apprenticed to the studio of the advertising designer Fritz Bühler. There his supervisor was Max Schmid, who went on to head design at the pharmaceutical giant, Geigy, where the new Swiss graphic design developed as a house style.

Chance and enterprise gave Gerstner the finest teachers and the most inspiring and fruitful connections. He wasted none of them. He visited Cassandre in Paris and came to know Tschichold in Basel. He joined Hans Finsler’s photography course in Zurich. As the youngest member of the Swiss Werkbund design association, he met Max Bill and Alfred Roth, the veteran architect who edited the monthly Werk. Pressed by Gerstner to report more on Swiss graphic design, Roth gave the 25-year-old a whole issue of the magazine to edit and design. That November 1955 issue was a turning point. Swiss graphic design was presented, for the first time, as a logical development of Modernism. His design of Werk was radical, too. Gerstner used a complex grid to accommodate the varying proportions of the work reproduced and he ranged the text left, unjustified, – a novelty attacked by some of the pioneers.

The founding fathers of graphic design admired by Gerstner were all painters, more artists than designers. And he, too, has had a continuous career as an artist. His first book, published in 1957, was a survey of the school of concrete-constructive abstract painting to which he belongs. The small, square Kalte Kunst? [Cold Art?], as it was titled, included his guiding lights, Max Bill and Richard Paul Lohse. Bill was probably the earliest to devise controlling grids for organising text and pictures; Lohse had devised one for the monthly Bauen+Wohnen in the 1940s. As an element of their typographic grids as well as their paintings, both Bill and Lohse used the square.

The square generated the grid he devised in 1957 for Markus Kutter’s experimental novel, Schiff nach Europa [Ship to Europe]. It is an exercise in styles: conventional narrative; play script; conversation that becomes loud argument; newspaper journalism, etc. Gerstner’s typographic language varies dramatically, but is disciplined by the grid – rigorously imposed, but flexible in use – and the restriction to only grotesque fonts. In this example of ‘integral typography’, the type makes the image.

Gerstner and Kutter met when the latter joined Geigy as public relations officer in the late 1950s, and they worked together on publications for the firm’s 200th anniversary in 1958. The chief outcome was Geigy Today, the first comprehensive demonstration of the new graphic design. The square format book used all the techniques of information design that have become standard practice – charts, annotated photographs, diagrams (organigrams, Gerstner calls them). He set the type (all Akzidenz) in unjustified columns, the method he introduced at Geigy in 1954.

In 1955 Gerstner and Kutter had put together pamphlets on planning, as radical in their typography – long lines of Monotype grotesque bold – as in their ideas. In 1959, they established their own design office and published another square book, The New Graphic Art, a survey that expanded the account Gerstner had given in Werk.

The work of this ‘two-man creative team’ in the early 1960s is far from the stiff ‘Swiss’ stereotype. (With a new partner, Paul Gredinger, an architect whose chief interest was in electronic music, the firm became GGK in 1962.) While Gerstner inherited the Modernist European tradition, he also grasped the conceptual ideas of the American New Advertising, where the message is inseparable from the form. He identified this as ‘Integral Typography’ in his most influential book, Designing Programmes, a collection of essays published in 1963. The idea of permutations was central to this volume, which presented ‘a method and an approach’ to design. As in chemistry, ‘the formula creates the form’. The essence of his permutational thinking is distilled in Think Program, which accompanied his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1973, and in Kompendium für Alphabeten (1972; later published as Compendium for Literates). Square, chunky and elegant, Compendium is an inventory of the permutations of type images available to designers. The possible styles and graphic treatments are exhaustively analysed.

As GGK grew to become a large advertising agency, Gerstner’s dreams of making a multi-disciplinary practice in the spirit of the Bauhaus faded. In 1968, to manage the huge Ford account in Germany, GGK moved to a new main office in Düsseldorf. The firm flourished, but by the beginning of the 1970s Gerstner withdrew into ‘semi retirement’. [Kutter had already lost one important client by admitting that advertising was ‘not serious’.]

After the 1960s, the decades record the jobs of a successful, conventional, business. GGK was bought by Trimedia, a PR agency, in the 1990s. ‘The last remnant of everyday aesthetics is being sacrificed on the altar of consumerism,’ writes Gerstner. Perhaps this is why his later personal work takes on a perverse eccentricity.

Does the work justify the claims that Gerstner cannot, in modesty, make for it? No reproduction can do justice to the startling effect of a whole-page broadsheet advertisement, the graphic playfulness, the incomparable typographic finesse and tense argument of his books, and no translation can do justice to the wit of the copywriting. (This is the English edition of the original German, published last year.)

The text setting, in Gerstner’s own uninvitingly eccentric Privata font, gives the book an other-wordly character, remote from today’s graphic design. Yet in his work and writings he deals with fundamentals of graphic design, as he did before the existence of the personal computer: ‘Designing programmes’ is what the future of graphic design is largely about. Karl Gerstner: Review of 5x10 Years of Graphic Design etc. reveals the history of that future, and shows Gerstner as an authentic pioneer.

Richard Hollis, designer, London

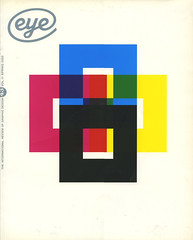

First published in Eye no. 43 vol. 11, 2002

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.