Spring 2019

The glyphic and the vedutic

Scott Gericke

various designers

Alfred Charles Parker

Design history

Illustration

Magazines

Reviews

Visual culture

Stick Figures: Drawing as a Human Practice

By D. B. Dowd. Designed by Scott Gericke. Spartan Holiday Books in association with Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, $39.95

D. B. Dowd is Professor of Art and American Culture Studies at Washington University, St Louis. Stick Figures contains intense evaluations of certain practical methodologies associated with illustration along with a range of correlative definitions of genre, style and image construction. The book presents a well researched roster of historic illustration, and Dowd’s writing is engaging and accessible. It is a self-consciously polemical book that invites argument.

Among many elements in his book, Dowd has conceived simplistic taxonomic charts that present comparative visual language terminologies. Largely embedded in cultural history, the charts use either twentieth-century US illustration or the aesthetics of Venetian and Florentine art. A typical example might be comparing the graphic with the painterly.

Dowd defines the differences thus:

The graphic is glyphic, a symbol, Florentine ‘Disegno’, vector-based, etc.

The painterly is vedutic, an image, Venetian ‘Colore’, pixel-based and so on.

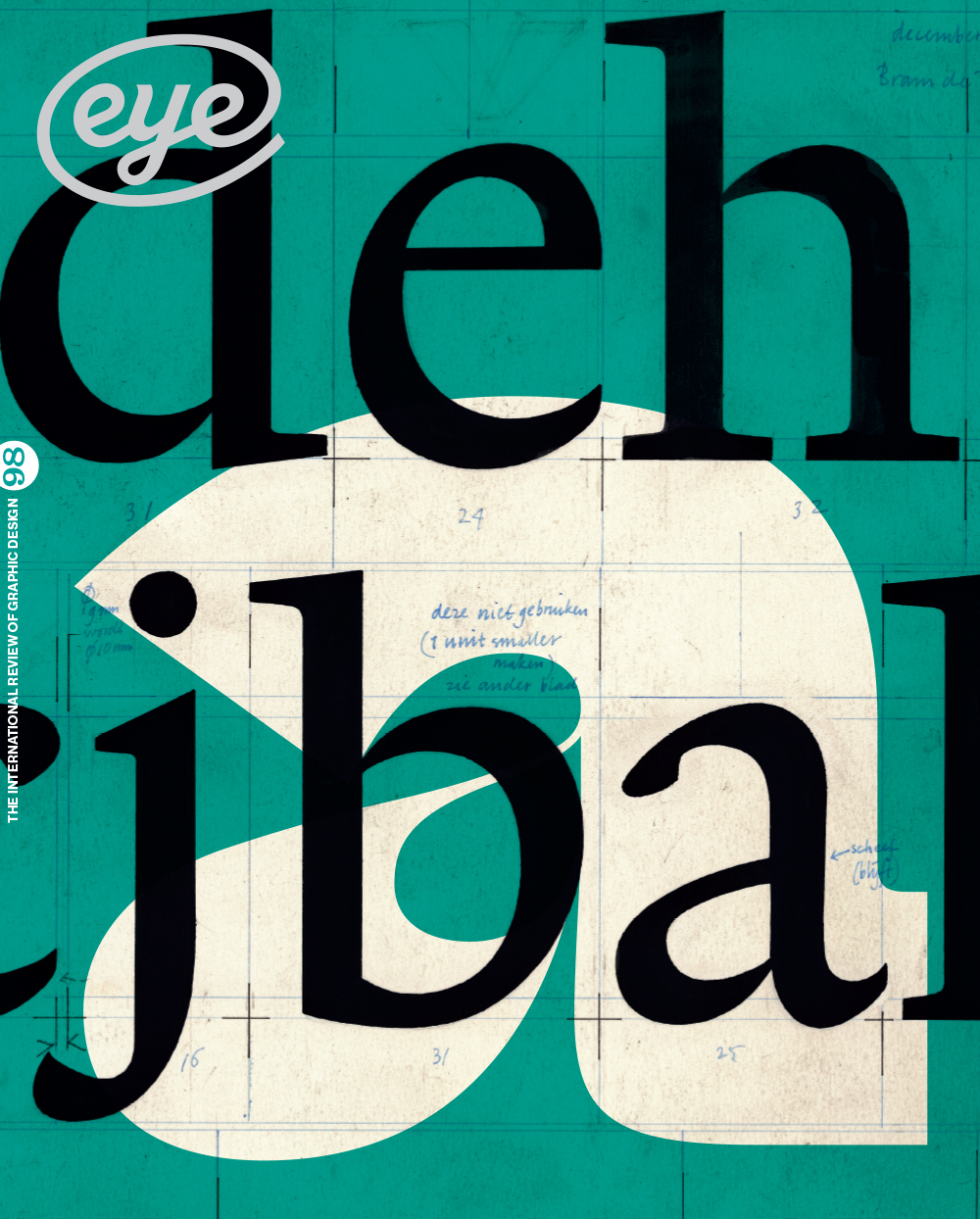

Top: Spread from D. B. Dowd’s Stick Figures: Drawing as a Human Practice, showing two-colour artwork by illustrator Alfred Charles Parker (1906-85), including colour tests and registration marks. Dowd writes that in the middle decades of the twentieth century, Parker ‘was a celebrated and well compensated creator’, working for magazines such as Cosmopolitan, McCall’s and Ladies’ Home Journal.

People have been debating these differences for decades. Ever since W. A. Dwiggins coined the term ‘graphic design’ in 1922 (see Eye 22) the debate has raged – where do graphics end and illustration begin? But that argument is not the essence of Dowd’s book. His overriding hypothesis is largely related to what drawing actually is; to whom it is for; and by whom. Furthermore, his overview focuses almost entirely on United States cultural history and illustrators such as Alfred Charles Parker, celebrated and prolific during his heyday but now largely forgotten, plus J. C. Leyendecker and the much more famous Norman Rockwell. Subjective in tone, the book is written overtly in the first person; the text imbued with personal anecdotes, observations and references to his own practice as an illustrator.

Dowd’s thesis argues that ‘drawing shouldn’t be about performance, but about process’. I disagree. ‘Performance’ defines context, completion, communication and message, impact and consequence. Dowd’s text supposedly underpins illustration but does nothing to support the fact that drawing is the foundation on which illustration is built. If drawing is the principal faculty of illustration then is it is about performance. Drawing is specific to solving problems of visual communication and facilitates that all-important procedure for externalising ideas: drawing in all of its creative and diverse languages is illustration. It can manifest as a fully contextualised piece of journalism, the presentation of new knowledge through primary research, the essence of an advertising campaign through commerce and promotion or as pure narrative fiction and entertainment.

Stick Figures includes sub-sections such as ‘Illustration as Cultural Practice’ and ‘Cartooning as Cultural Practice’, but there is little mention or analysis of the aforementioned contextualised remits and the true power and influence that illustration can wield to global audiences.

Central to Dowd’s contentions is this: ‘We have misfiled the significance of drawing because we see it as a professional skill instead of a personal capacity. This essential confusion has stunted our understanding of drawing and kept it from being seen as a tool for learning above all else’. I would question this – kept its visibility as a process for learning from whom? The illustrator James McMullin stated: ‘We draw to understand our subject matter.’ Many of the great polymaths of the Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment are known primarily as ‘artists’ as well as scientists, inventors, philosophers, naturalists, architects, etc. We have all marvelled at the avid historic ‘doodlings’ of those who were engaged in primary research and the initial concept sketches for those well known theories, inventions, and designs and built constructions. I myself have had the honour of leafing through Charles Darwin’s sketchbook that accompanied him on his famous HMS Beagle explorations.

At its core, drawing is as much an expression of learning as anything else and widely known to be and science is no exception. Enter the reception class in any school and we will see very young children engaged primarily throughout the whole day, drawing and ‘colouring-in’, expressing their imaginations and observations. Anyone and everyone can ‘have a go’ at drawing – most people do. There is nothing new here. Take, for example, the ballpoint pen sketch a carpenter presents when explaining the work he intends to undertake.

Following on from this, Dowd explains that this book ‘… is premised on an embrace of the citizen as a maker of form and meaning. The argument is based on direct expression through modest means.’ I find this somewhat patronising and certainly not an original assumption.

Would I recommend this book? Probably, although not for what it sets out to do. However, it does contain a very well researched roster of historic illustration – the author has full access to the Rockwell Museum’s collection. For anyone interested in historical developments related to nineteenth- and twentieth-century US illustration plus certain theories about drawing practices and definitions, it may be for you.

Alan Male, Professor Emeritus of Falmouth University; academic, author and illustrator, East Sussex, UK

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.