Summer 2008

The idea will not be found in a book

Paul Rand: Conversations with Students

Edited by Michael Kroeger. Foreword by Wolfgang Weingart.<br>Princeton Architectural Press, US dollars 19.95<br>

This slim book of 80 pages will take maybe one hour of your time. The main text is an edited transcript of two conversations at Arizona State University in 1995, a year before Paul Rand’s death at the age of 82, plus ‘thoughts’ by former students and colleagues. If you have read any of Rand’s own books and / or Steven Heller’s monograph about him, ask yourself: what new thing have you learned about this esteemed American graphic designer? Or, if this is your first taste of Rand, how is this useful in 2008?

The first conversation is with Michael Kroeger (who teaches design at ASU), with brief comments by another faculty member – and no students present. They discuss John Dewey’s Art as Experience, which Rand has always quoted and praised, and other readings he values; and discuss some basic design principles. Rand teases the other two about needing a definition of design: ‘Design is relationships. Design is a relationship between form and content. What does that mean? That is how you have to teach it until they are absolutely bored to death. You have to keep asking questions.’ Culture and variable meanings are broached and dismissed: ‘You’re not talking about design, you’re talking about semiotics, the meaning of symbols. That has nothing to do with design.’ Rand returns to design as form and content, and states that the idea will not be found in a book.

The second conversation is between Rand and a student group. To a faculty member’s question ‘What is important that we learn?’ Rand replies with the histories of art and design and aesthetic philosophy. To a question about materials, Rand says, ‘It is important to use your hands, that is what distinguishes you from a cow or a computer operator.’ He breaks down his creative process as preparation (problem investigation and forgetting), incubation and revelation (idea put down and evaluated). There are questions about working with clients and about logo design.

In the following short texts, Philip Burton describes Rand’s compassionate and ornery teaching at Yale and the Brissago summer school; Jessica Helfand recalls her experience of Rand as graduate advisor; Steff Geissbuhler remembers Rand as a curriculum reviewer and puckish critic of one of his projects; Gordon Salchow describes being his student; and Armin Hofmann recounts their collaboration in Brissago.

Given all this, you might think this book an ‘Essential Rand’. True, there are characteristic and illuminating nuggets of his thoughts; but the sessions in Arizona are an example of the celebrity designer doing a turn for one more group of faculty and students – in this case, near the end of his life.

Paul Rand was an exacting and attentive teacher. He was a careful and graceful writer on aesthetics, art and design, producing four elegant books between 1947 and 1996. Here he is reduced to answering simple questions, grabbing for favourite quotations and trotting out tiny complaints. To see Paul Rand, a famous and beloved curmudgeon, reduced to design bromides is sad.

It is sadder still to compare this with the rest of the ‘Conversations with Students’ series (each running 96-112 pages), which previously focused on architects and their conversations with students. It is good news that the publishers have branched out into other design disciplines; the bad news is not that the new branch is graphic design, nor that Paul Rand is the representative, but that graphic design and Rand together are so poorly represented. Koolhaas (1996), Kahn (1998), LeCorbusier (1999), Calatrava (2002), Peter Smithson (2005) and McHarg (2007) have each been well served by knowledgeable and sympathetic editors framing the selections, the texts selected from documented important lectures and substantive Q+A sessions with students, handsome little books with striking designs.

Rand gets a thin transcript, comprising all of seventeen pages, that does not compliment him or his interlocutors. It is padded with full bleed photos of his visit, enlarged quotes, some of his work (printed in blue only) and some ASU student and faculty work (not diminished in blue). The reminiscences provide adequate framing, but remind us of a more vibrant Rand at the top of his game. The padding extends to an uncredited design bibliography. Given Rand’s repeated imperative to read and be informed, one might think this is his reading list (which could be useful) but it cannot be, for there are books that Rand dismissed, and books published after his death. This is in fact from Kroeger’s website, from whence came the Rand transcripts. Why is he cleaning house in this manner? And why now? One can only guess this is intended as an homage to a designer admired and respected; but sometimes an homage can be a muddled disservice, and this is one to both individual and discipline.

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 17 2008

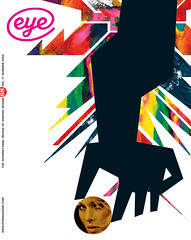

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.