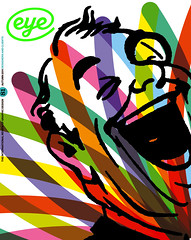

Autumn 2011

The impact of Vorticism

The Poster King

Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London<br>14 September–18 December 2011Is it a sign of the growing acceptance of graphic design as a legitimate subject for the traditional art gallery that ‘The Poster King: Edward McKnight Kauffer’ at London’s Estorick Gallery feels so conventional? Stretched across two small rooms, the exhibition adopts an undemanding biographical approach, tracing Kauffer’s journey from Montana, where he was born in 1890, via a brief stay at Chicago’s Art Institute, to his work for London Underground and beyond.

As if to situate the exhibition within the familiar world of art, the show begins and ends with paintings by Kauffer, the first being landscape paintings of his early days in the UK and the last being a series of works created for Shell.The theme of the relationship between art and design continues, with a good attempt at identifying the impact of Vorticism on Kauffer’s design. Walking through the exhibition it becomes clear how Kauffer shares the fascination with colour and the vigorous play of objects across the surface characteristic of David Bomberg paintings such as The Mud Bath (1914). There was certainly something specific to the Vorticist approach that made it more predisposed than, say, Futurism to the sphere of commercial art. The use of bright colours and strong lines to symbolise the dynamism of modern society seems especially suited to the promotion of transport for which Kauffer would become so celebrated. Yet, although not examined in any great detail, the use of light and shade in Ludwig Hohlwein’s posters is also revealed as a key influence on Kauffer’s distinctive style. Kauffer instinctively saw that the German Plakatstil approach was perfectly suited to the acceleration of modern life that demanded modes of communication that were easily digested.

Such influences can be detected in one of the most striking works on display, Kauffer’s 1921 poster Winter Sales are best reached by Underground. In one of the most perceptive observations of the exhibition, the point is made that while many of the original spectators of Kauffer’s work would never consider viewing the work of Cubism or Vorticism in a gallery space, they would happily spend many minutes in front of a highly abstract work such as this. For Kauffer, as Wyndham Lewis noted, ‘the tunnels of the Tube became … his subterranean picture galleries’. The display of his work on the London Underground became an event, with billboards often announcing the imminent arrival of a new Kauffer poster.

One of the surprises of the Estorick exhibition was the small array of Kauffer ephemera, the book illustrations, invites and leaflets that are the bread and butter of a designer’s output but rarely make it into a history of design publications. Here it can be seen how, although American, Kauffer was just as much a part of that inter-war flowering of British illustration as his contemporaries Edward Bawden, Edward Ardizzone and Paul Nash. Indeed, it could be argued that it was Kauffer’s work that did most to bridge the gap between art and design. Nash himself said: ‘Kauffer is responsible, above anyone else, for the change in attitude towards commercial art in this country; and it was the courage and aesthetic integrity shown in his early battles with the “plain business man” that made it possible for Kauffer to advance and eventually consolidate his position.’

For what is a relatively small space, ‘The Poster King’ offers a comprehensive overview of Kauffer’s oeuvre. It was wonderful to see posters such as the Soaring to Success! Daily Herald – the Early Bird (1919), a tall work that is often only reproduced in part in historical anthologies of graphic design.

While condensed, the narrative sketched out by the curators, Roberta Cremoncini and Christopher Adams, is detailed and satisfyingly complete. However, I left the exhibition with the doubt that the deceptively holistic nature of biography – an approach that can be more about satisfying the curator’s need for completeness, than about offering a faithful rendition of the inconsistencies of the individual examined – is suitable for the cracked and splintered bastard of a discipline that is graphic design.

First published in Eye no. 81 vol. 21 2011

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.