Spring 2010

The mystery of frozen locomotion

On the Move

Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London. 13 January–18 April 2010.This exhibition explores the static, two-dimensional representation of movement. In the catalogue (and in his lucid talk at the show’s opening), curator Jonathan Miller makes a philosophical distinction between ‘events’ and ‘actions’, which are peculiar to living organisms. Many of the most striking attempts to record such actions are on display here, from Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge, to Harold Edgerton and Gjon Mili.

The choice of the Estorick as the location for Miller’s engaging mix of art, science, technology and visual culture is significant. This small, independent, north London gallery holds several key works from the Italian Futurists, the first significant artistic movement that attempted to visualise motion. Giacomo Balla’s 1912 oil painting Hand of the Violinist, for example, shows the direct influence of Marey (1830-1904), the French ‘chronophotographer’ whom Miller places at the heart of his survey.

Analysis of the Flight of a Seagull, Étienne-Jules Marey (1887)

Bronze, 16.4 x 58.5 x 25.7 cm. Dépot du Collège de France, Musée Marey, Beaune, France.

Marey was a doctor (as is Miller) but spent most of his life finding increasingly ingenious ways to analyse and record movements of birds, animals and people. On display is his extraordinary ‘photographic rifle’, which produces a circular print of twelve images.

Miller contrasts Marey’s work with the more self-publicising methods of Muybridge (born Edward Muggeridge), the Englishman whose sequential pictures of horses in motion were first commissioned by an American race-horse owner, Leland Stanford, allegedly to settle a wager. The pictures challenged the received wisdom of conventional paintings – that horses ran with feet splayed in a ‘rocking horse’ position. Paintings of hunting scenes would never seem the same again.

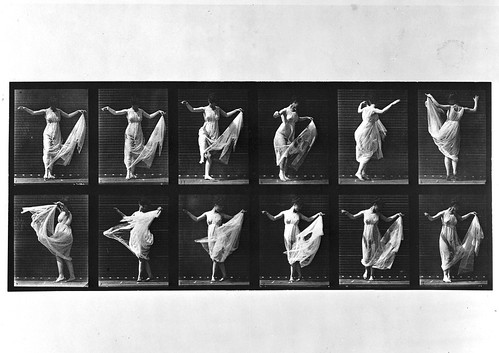

By the 1880s, with the support of the University of Pennsylvania, Muybridge’s output was prolific, with a stream of memorable sequences capturing animals, men and women in individual successive cells of frozen activity. A few of these were also on display and animated in ‘Points of View: Capturing the 19th Century in Photographs’ at the British Library, 30 October 2009–7 March 2010.

Miller points out that although Marey was much more of a scientist than Muybridge, his scientific legacy was ultimately slight, a result of his reluctance to conduct intrusive experiments on actual bodies, and what the curator describes as ‘his seemingly scientific commitment to the idea of the body as a machine’. (See also ‘Machine head’, pp.16-19.)

Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904). Collotype print, 46 x 59.1 cm from Females (Semi-Nude) & Children. Dancing (Fancy), 1887. Courtesy Kingston Museum and Heritage Service.

In contrast, Muybridge’s experiments were narrative rather than scientific, argues Miller, writing: ‘This is particularly obvious when Muybridge addresses himself to female movement. More often than not these sequences are distractingly picturesque, condescendingly domestic, trivially playful and in some cases teeter temptingly on the edge of soft pornography.’ He cites as an example the almost burlesque print of ‘Two women walking arm in arm and turning around, one flirting a fan’.

Even pictures with hardly a trace of human form tell a story: Adolph Braun’s apparently deserted Panorama of Paris (1867) shows the teeming city, taken at an exposure so long that all movement is reduced to a blur. Miller’s caption joins the dots: ‘From Lartigue’s distorted image of a racing car, to Bertelli’s famous “continuous” portrait of Mussolini, Jonathan Shaw’s images of sportsmen and the flowing forms of Geoffrey Mann’s sculptures, blur continues to constitute a powerful means of suggesting movement of such speed that the eye is no longer able to distinguish the contours of the object or figure in motion.’

‘On the Move’ is not exclusively concerned with photography, art, design or science, yet it deals with all these subjects. Miller’s perspective on a subject that, he argues, remains underexplored and mysterious will pique the curiosity of anyone involved in images, both animated and frozen.

John L. Walters, Eye editor, London

First published in Eye no. 75 vol. 19 2010

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.