Summer 2014

Unravelling pages

A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley

Written and designed by Warren Lehrer<br> Goff Books, $34.95, £20.62, hardback<br>

Warren Lehrer is best known for French Fries (Visual Studies Workshop Press / EarSay Books, 1984). In an era before computer-aided layout, he made a work that broke the grid – and possibly the crystal goblet – creating lyrical pages with undulating fonts, images, and spectacular tints, in which the design was not mere accessory to story but an integral mode of its performance. For all its acclaim and influence, French Fries remains an out-of-print, avant-garde work. In his most recent book, Lehrer continues to make design a constitutive element, telling the story of the fictional author and designer Bleu Mobley through book covers, fonts, supporting documents, illustrations and an endless series of concepts for innovative books. Though A Life in Books is not nearly as technically groundbreaking as French Fries, Lehrer has succeeded in finding a much wider audience for his ‘illuminated’ novel through an intense series of readings and interviews, as well as a supportive publisher, Goff Books. A Life in Books challenges readers to rethink the relations of the novel to the image, and of the whole book to our contemporary world.

Lehrer follows his protagonist from childhood in the 1960s to the present. From the beginning, the process of composition is the centre of Mobley’s life. At school, Mobley is drawn to the vocational training offered by the letterpress shop, where his teacher informs him that ‘you’re going to be both the writers and the printers, like Benjamin Franklin and William Duane were in the early days of America.’ Mobley begins writing, printing and binding his own small books, literally drafting the sentences by picking the type from the case, combining the processes of writing and design in a single gesture.

Though the story of Mobley’s life reads as a conventional novel, it is a life that celebrates design, and Lehrer lovingly evokes the vocabularies of typography and printing in particular: tails and finial swashes, do-si-do bindings and a colophon that lists the 59 typefaces to be found in A Life in Books.

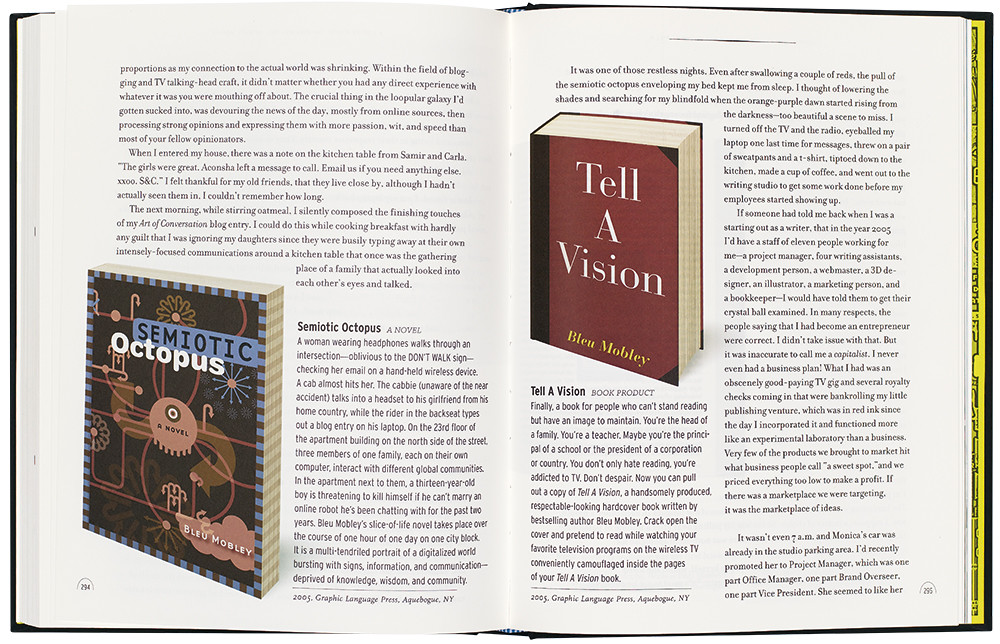

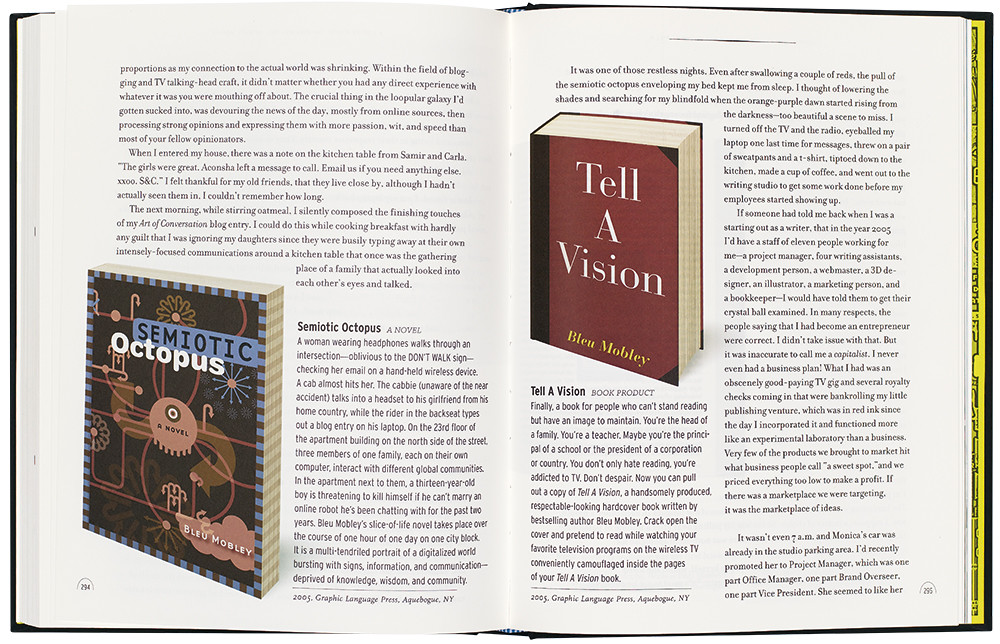

Mobley’s first-person narrative is constantly interrupted by covers, blurbs, critical appraisals and excerpts from the books that define his life. Almost all of them are high concept. For instance, there is an early novel entitled The Switch, which is summarised by a snarky fictional critic: ‘It is dizzying enough slogging through a novel where every character is simultaneously someone else, but then halfway through The Switch, the reading orientation flips 180 degrees, forcing the reader to physically turn the book upside down. Once vertigo sets in you realise this device is nothing but a cheap trick to get you to notice the book’s palindromic cover design that forms a face from both orientations.’ Then there is Narcissistic Planet Disorder, a satire of Cold War excess that fails commercially when bookstores can’t find shelving for a book that stands 28 inches tall. Lehrer has said that many of these ideas come from his own notebooks; through his fictional protagonist he is able to communicate them as concretely realised designs.

While Mobley’s early books are aggressively experimental, his prodigious output suddenly spawns bestsellers, such as Buy This Book Or We’ll Kill You, a satire of the publishing industry, or a children’s pop-up book on the history of capital punishment, How Bad People Go Bye-Bye. Mobley goes on to start a self-help empire under the pen name Dr Sky Jacobs, and he eventually hires a team to write the dozens of books in the ‘I Could Love You So Much If Only’ series, the bland covers a spot-on impersonation of the worst of corporate book design.

Mobley then invents Blain Masters, a right-wing intellectual whose series of books argue for the privatisation of everything. He even hires an actor to play the role of Masters on talk shows. Mobley himself thus becomes something of a microcosm of the commercial publishing industry, its aesthetics and its flaws, although it is hard to tell just how much Lehrer is satirising the worst excesses of publishing or how much the whole is simply being celebrated. This is a complex issue throughout, as the book’s tone vibrates with a very American gee-whiz optimism that makes it hard to understand whether Lehrer’s Mobley has a point of view beyond the affirmation of books in any form. That tone combines with an often superficial treatment of intractable problems. One wishes for a far more nuanced and complex narration that could better match and make use of the brilliant visual strategies. For instance, the collage cover for Mobley’s novel, The Megalomaniac, with its mismatched eyes and broad strokes of pink, white, and blue, conjures up a vivid sense of violence, just as the Ben Day dots and muted colours of Puss Dude create an effective cool evocative of its title character. Yet the subjects that Mobley most often takes on – drive and desire, economic inequality, racism, sexuality and mortality – all too often dissolve into an affirmation of his own glib universalism.

Mobley’s final project reaches for transcendence as he looks to the sky and has ‘a vision of books unravelling: pages peeling free of their bindings, the wind catching each leaf, endowing them with the ability to float, bob, dive, somersault, dance through the domed proscenium.’ This conception is beautifully written and challenges the reader to think about the book as an object with limits that should be overcome. Yet even as the prose so wonderfully evokes a sky filled with flying pages, Lehrer struggles unsuccessfully to bring that vision of light and motion to life, as pastel pages drift around indifferent skies, looking more like the clichés of pharmaceutical advertising than a convincing vision of unbound books.

Goff Books has spared no expense on A Life in Books, an image-wrapped, eight-by-ten-inch hardcover, richly illustrated with vibrant colours throughout. In many ways, the book succeeds beautifully as a hybrid between the graphic novel and the novel, with dense walls of text that alternate with visual extravagances. It suggests new potentials for popular literary fiction to break with the older tradition of the illustrated novel by making the images take part fully in telling the story. Lehrer’s book nonetheless remains a novel, with its prose narrative always in the foreground. Lehrer’s subtitle, An illuminated novel, is thus helpful and more than justified. While artists’ books and experimental fiction both have a long history of this – and more recently one might think of the visual strategies of experimental novelist Steve Tomasula – Lehrer shows that ‘illumination’ can be effective with the prose of the traditional novel. Lehrer’s book has been winning awards and warm reviews almost everywhere, strongly suggesting that this innovative novel is finding its audience.

Cover of A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley, written and designed by Warren Lehrer.

Top: A spread showing two of the many books supposedly written by the improbably prolific protagonist Mobley.

David Banash, Professor, Department of English at Western Illinois University

First published in Eye no. 88 vol. 22 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 88 looks like at Eye before you buy on Vimeo.