Summer 2022

Waiting at the intersection

George Maciunas

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

Ed Ruscha

Design history

Graphic design

Reviews

Art & Graphic Design: George Maciunas, Ed Ruscha, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

By Benoît Buquet. Yale University Press, £35

Art & Graphic Design is a tantalising title, encapsulating a relationship, or at least an adjacency, that is always present, sometimes explicitly alluded to, but never definitively addressed. Designers are often fascinated by a visual practice in which the maker enjoys an enviable autonomy usually unavailable to themselves. Designing catalogues for artists gives the designer a ringside seat in the art world, but underlines the subservience of the relationship. On the other side of the coin is art that depends to some degree on graphic design – on its techniques and conventions – for its expression. The most likely exponent is an artist educated as a designer, as was the case with George Maciunas and Ed Ruscha, two of Art & Graphic Design’s case studies.

Any account of the ‘art & graphic design’ relationship (for Benoît Buquet, the ampersand signifies their interlacing) must be situated somewhere and will be determined by that viewpoint. It’s possible to imagine a researcher who could address the subject equally from both directions, but it isn’t very likely. It would require degree-level knowledge and career experience of both fields and, even more elusively, a non-hierarchical openness and sympathy for both activities. Buquet, a French associate professor of contemporary art history at the University of Tours, is a rare exception in his sensitivity to design. His similarly titled collection of essays, Art & Design Graphique (published in French and untranslated), was favourably reviewed by Richard Hollis in Eye (no. 90 vol. 23). Nevertheless, art is Buquet’s disciplinary background and departmental home and it inevitably shapes his perspective in Art & Graphic Design.

The book is the product of a series of evidently well funded research opportunities, starting in 2008 when Buquet received a grant to work on Maciunas and Fluxus at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. His thoroughness as an archival researcher is one of the book’s strengths and, as an art historian, he expects to engage closely with objects and analyse them in detail. Design writers could learn from this. But the book’s broader purpose is not clearly defined and the connections between Maciunas, Ruscha and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville aren’t based on any hypothesis or ‘overall concept’, which such a decisive selection might lead one to expect. ‘I simply refuse to make the exposition of my research, however precise and meticulous, the pretext for formulating a law on the relationship between art and graphic design,’ writes Buquet. He jauntily assigns that exercise to readers ‘should they wish to pursue it’. (The book is translated, often a little awkwardly, from French.)

Cover of Art & Graphic Design. Top. George Maciunas’s, USA Surpasses All the Genocide Records!, 1966.

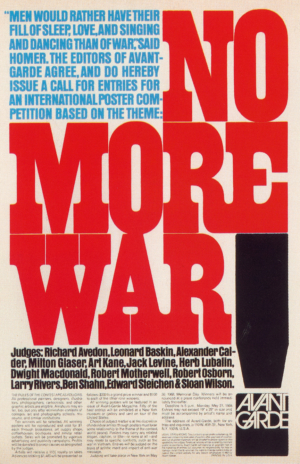

An all-purpose ‘law’ sounds implausibly reductive – a straw man – but it would have been entirely feasible to make some broader connections. In one of the book’s most interesting sections for readers approaching the art / design interface from a graphic design perspective, Buquet considers Maciunas’s typography for Fluxus (see Eye no. 7 vol. 2) in relation to Herb Lubalin’s ‘typographics’ – seen, for instance, in Lou Dorfsman’s Gastrotypographicalassemblage for the CBS cafeteria. Here, the promise of the book’s title is fully delivered, but elsewhere, opportunities to extend the discussion are missed. Buquet quotes Rudy VanderLans’s excitement on seeing Ruscha’s books for the first time in 1986: ‘I discovered that my options as a graphic designer had expanded tenfold.’ This is a useful piece of evidence, but there is no discussion – not even in an endnote – of what VanderLans learned from Ruscha, even though he went on to produce photobooks himself. The final section about Levrant de Bretteville (see Eye no. 8 vol. 2) is perhaps the most valuable because her work has received insufficient attention. However, its focus is on graphic design and feminism rather than on art and it feels like it belongs to a different history and book. For Buquet this ‘discontinuity’ is deliberate, but I wasn’t convinced by his brief justification.

Herb Lubalin’s No More War!, detail, 1967.

While Art & Graphic Design uncovers many fascinating ‘micro-narratives’, the assumed reader appears to be someone from the art world who is habitually inclined to overlook the contribution of graphic design to art-making. ‘The relationship between Pop Art and graphic design is often taken for granted,’ writes Buquet, ‘with the underlying assumption that it would be pointless to delve deeper into graphic design and popular cultures.’ The illustrations give the book a broader appeal, but the text will be mainly of interest to designers who already have a working knowledge of its subjects, which they are keen to expand. For the serious graphic researcher, the book confirms that there is no substitute for diving into the archives.

Rick Poynor writer, Eye founder, professor of design and visual culture, University of Reading

First published in Eye no. 103 vol. 26, 2022

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.