Autumn 2019

Who cares if you read?

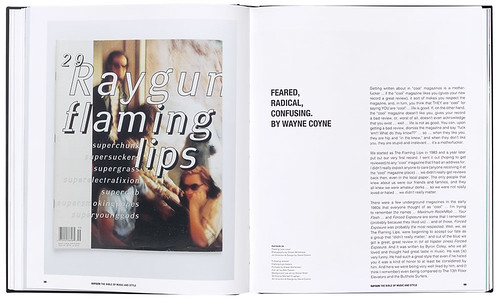

Ray Gun: The Bible of Music and Style

By Marvin Scott Jarrett. Essays by Liz Phair, Wayne Coyne, Dean Kuipers and Steven Heller. Design by Studio Roxane Zargham, Rizzoli, $65, £50

David Carson is indelibly linked to the notion of the ‘end of print’, encapsulated by the title of his famous book of that name. Yet it is perhaps more pertinent to link him to the end of reading. The head-on collision between Carson’s graphic design and the act of reading reached its apotheosis with his notorious Bryan Ferry spread for Ray Gun, which he rendered entirely in Zapf Dingbats. No one seemed to mind: did anyone buy Ray Gun for the writing?

The serious music press had always been about the writing. It wasn’t that Ray Gun, under the impassioned ownership of Marvin Scott Jarrett, did not commission writing. Rather, it was that the magazine’s design and art direction relegated it to a subsidiary role – or, put less charitably, obliterated it in a firestorm of mangled type, dysfunctional photography, and deranged layouts. But in the present era of ‘skim-reading’ and the rumoured death of longform reading due to our digitally scrambled brains, perhaps Carson’s disinclination to make texts readable was prescient.

Ray Gun was not the first publication to prioritise the image over words. Avant-garde journals had been doing it since the early twentieth century; the underground press of the 1960s pushed legibility to the edge of comprehension; and Emigre showed what could be done if you used a computer and dispensed with editorial design conventions.

Ray Gun: The Bible of Music and Style is a bold attempt to tell the story of this short-lived and influential publication. Magazine spreads are laid on the page like canvases, reinforcing the widely held view that Carson was painterly in his approach to graphic design.

The book, with its readable typography and conventional layout, is a typical product of a major publishing house. While designers might yearn for a more dynamic book design, the sober approach succeeds in highlighting the transgressive nature of the publication.

Front cover Ray Gun no. 29. Photography by Shawn Mortensen. Art direction and design by David Carson.

The book provides a series of texts that make a strong case for Ray Gun’s importance at a critical moment before the internet transformed the way music fans acquired and read about music. Steven Heller argues that Ray Gun deserves its position as a significant landmark in the graphic design terrain. As with other great moments of rebellion, it caused a schism – this time between traditionalists and a new generation of computer-savvy designers. Carson’s typography may have been ‘difficult to decipher’, notes Heller, but it was accepted that his dissident design aesthetic was what gave the magazine its ‘panache’.

Musician Liz Phair examines the commercial politics of Ray Gun with great insight: ‘When you buy a music magazine, and you can’t read the text or tell whose face is featured in a story, it exposes the true nature of the transaction … Labels want their artists to make impressions in the marketplace. Advertisers want their products to be associated with the artists. Magazines want their circulation numbers to increase.’

As she points out, Ray Gun was ‘deliberately sabotaging its sponsors in all of these categories’, while at the same time building a dedicated following among a new media-literate, image-loving generation weaned on MTV.

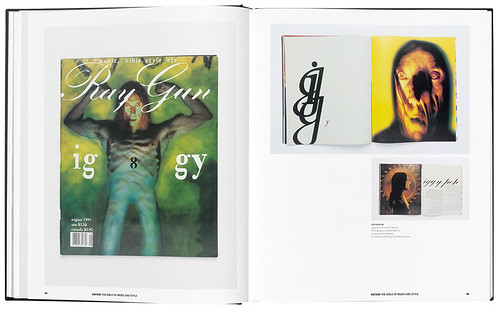

Front cover and spreads from Ray Gun no. 08. Photography by Matt Mahurin. Art direction and design by David Carson.

Ray Gun, founded in 1992, rode in on the back of grunge, that hybrid amalgam of punk and metal that was, for some music fans, the last hurrah of the independent spirit in pop music. Ray Gun spoke in a visual code that communicated with followers of grunge and alternative rock acts. And as with any revolutionary moment in graphic design, it required a willing client and a designer brave enough to lead the revolution. Jarrett found his leader in Carson – a talent and an ego strong enough to leap the barricades.

After Carson quit, the task fell to Robert Hales. Chris Ashworth took over in 1997 for the magazine’s final three years, latterly sharing the role with Amanda Sisson. Ashworth has called his work ‘Swiss Grit’, and while a bat-squeak of Swiss antecedents can be detected in the layouts, it is the distressed Letraset-left-out-in-the-rain look, coupled with a more measured poise that distinguishes Ashworth and Sisson’s ethos from Carson’s more freeform approach.

As with previous upheavals in graphic design, the Ray Gun style became the go-to style for anyone who wanted the instant patina of coolness. Bands and musicians used ‘ugliness’, distressed lettering and the visual tropes pioneered by Ray Gun to signal their distance from the mainstream record industry, which, in the 1990s, was on a mission to sanitise the iconography of music for a mass market. Nothing kills a visual style quicker than its adoption by ad agencies and corporates. But this book shows that for a brief moment, Ray Gun was a thrilling change of gear for graphic expression – so long as you didn’t want to read the articles.

Adrian Shaughnessy, designer, writer, educator, publisher, Essex

Front cover of Ray Gun: The Bible of Music & Style featuring Chris Ashworth’s Ray Gun masthead.

Top. Opener for the ‘Hot for Teacher’ feature by Bob Gulla in Ray Gun no. 19. Art by Floris Andrea. Art direction and design by David Carson.

Read the full version in Eye no. 99 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.