Autumn 2013

Wordplay for a picture palace

Le Gun

Mario Wagner

Alexis Deacon

Peter Biľak

Luke Pearson

Abake

Sam Winston

Na Kim

Oded Ezer

Johnny Kelly

Jim Kay

Stuart Kolakovic

Némo Tral

Reviews

Sky Arts Ignition Memory Palace

Victoria and Albert Museum, London SW7<br>18 June-20 October 2013<br>Memory Palace

By Hari Kunzru et al<br>Designed by Sara De Bondt Studio<br>V&A Publishing, £12.99

In classical texts on the ‘art of memory’, the student is advised to visualise objects, reminders, at various points inside a building. To recollect a sequence of things or ideas, the student imagines walking through the building, collecting the objects one by one. The building, which can be real or imaginary, can be termed a ‘memory palace’ – which is also not a bad description of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

For the exhibition ‘Memory Palace’ at the V&A, sponsored by Sky Arts Ignition, Laurie Britton Newell and Ligaya Salazar commissioned a text from the novelist Hari Kunzru, then asked twenty illustrators and graphic designers – including Le Gun (see Eye 64) and Peter Biľak (see Eye 75) – to respond visually. Kunzru’s text has been handsomely printed in a small hardback, along with concept sketches by the artists and a wordless picture story by Robert Hunter that shows the process of putting the show together.

Kunzru imagines a not-too-distant future in which technology has been wiped out and our civilisation destroyed, in an event called ‘the Magnetisation’. Our descendants, clad in kilts and ruled by the sinister Thing, scratch a living among the ruins of our cities. They have a broken, patchy knowledge of the past: they believe that in the time called ‘the Booming’ their forebears ruled the world through wondrous machines called pewters and qwertys; they would gather in internets and mark the passing of the seasons in religious ceremonies called recycling. The laws of the universe were handed down by the Lawlords – Lord Ferryday, Milord Newton; it was a time of accounting, when nature was measured and caged. Since the Magnetisation, in an age called ‘the Withering’, people have rejected number, science and memory in favour of a life closer to nature. Some look forward to ‘the Wilding’, a time when barriers between man and nature will vanish; a heretical few, Kunzru’s narrator among them, have revived the art of memory in an effort to recapture the past and record the present.

Jim Kay’s intricate reliquary or shrine for ‘Milord Darwing’. The doors show in incidents from Kunzru’s narrative. Kay said: ‘The text is everything.’

Top: Le Gun’s installation for the ‘Memory Palace’ exhibition, a fox-drawn ambulance.

Kunzru wears his influences on his sleeve, including Richard Jefferies’ early science-fiction novel After London and Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (his punning games with real names such as ‘Lady Mary of the Cure’ could come straight out of Hoban). The arrest and interrogation of his narrator by agents of the Thing is a re-run of Winston Smith’s ordeal in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. But Kunzru adds some original touches – green consciousness and closeness to nature are much less benevolent here than in most SF; and where Orwell’s rulers only tried to control memory, the Thing wants to abolish it. It is not all SF, either: the interrogator’s pronouncement that ‘the world is not made of facts’ seems to mock the opening of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-philosophicus: ‘The world is the totality of facts, not of things.’

The responses to Kunzru are enjoyably various: infographics, strip cartoons, sculptures, cabinets of curiosities, some typographical play. The quality of individual pieces is uneven but the mix works well. Literal, linear work, such as Luke Pearson’s graphic novelisation of the narrator’s arrest and interrogation and Némo Tral’s portraits of shattered London, provide concrete context for more conceptual, abstract work, such as the useless technological bric-a-brac assembled by the collective Åbäke, or Sam Winston’s ploddingly symbolic triptych of watch, book and SIM card in front of a swirling periodic table. Even so, a few pieces – including Na Kim’s ‘advertising billboard filled with abstract graphic symbols of organising tools’ and Oded Ezer’s film loops – seem disconnected from the project.

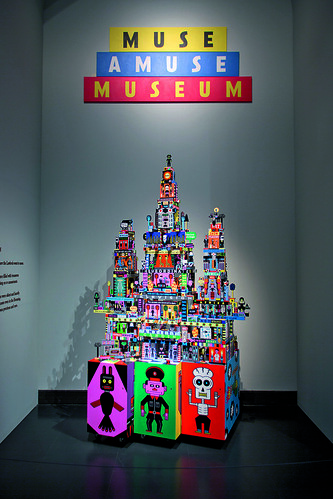

Henning Wagenbreth’s installation of wood, acrylic and canvas, which can be packed away (in the boxes at the bottom), for easy transport and whose contents can be arranged differently on each reassembly.

Some of the artists spark off the satirical edge of Kunzru’s vision: the collective Le Gun has illustrated a muddled future mythology of the NHS by building a striking, cartoonish hospital wagon, a medicine show drawn by foxes and driven by a top-hatted Baron Samedi figure (is this any more muddled than our contemporary myths of the NHS, though?). Stuart Kolakovic’s grisly Orthodox icons and Jim Kay’s handsome, gilded reliquary for ‘Lord Darwing’ both play oddly sincere games with religious imagery.

Mario Wagner uses collage to depict the Magnetisation as a kind of secular, technical Rapture – cars and planes crashing, bodies (mysteriously hooded, like terrorists or hangmen) caught in mid-air. Alexis Deacon, best known as a children’s illustrator, evokes Hogarth and Goya in his drawings of interrogation and torture: comics fans may detect echoes of D’Israeli’s artwork for the 2000AD strip ‘Stickleback’, with its combination of steampunk and Celtic mythology.

The exhibition ends with Johnny Kelly’s ‘Memory Bank’ – visitors are invited to write or draw a memory on a screen, to be incorporated into a poster that is printed out once a week for the duration of the exhibition. The continuity with Kunzru’s ideas is plain, but most of us will find it hard to get beyond banality or whimsy – Kunzru’s very serious questions about history and memory are lost; and for me this had the whiff of a newspaper website’s desperate plea to readers to ‘get involved with the debate’.

Cover of the novella Memory Palace, designed by Sara De Bondt Studio.

Robert Hanks, journalist, critic, broadcaster, London

First published in Eye no. 86 vol. 22 2013

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 86 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.