Autumn 1992

Worth the paper it's printed on?

Marketing: paper samplers

Laurel Harper on paper samplers

As the design profession gained prominence in the last decade, it also caught the eye of the more than $123 billion American paper industry. The 600 or so mills, realising that designers are major specifiers of their most expensive paper lines, began to target that market with an intensity that only commercial America could muster. Often, mills hired designers themselves to create glitzy promotional documents with which to flood the market.

Most of these pieces ended up in the rubbish bin. And while that might have been OK in the ‘me too’ 1980s, the new ‘green’ mindset of Americans in the 1990s is causing many designers to cringe as they look back on those years. San Francisco-based Michael Vanderbyl voices the feelings of many of his fellow designers when he says: ‘I get tired of paper promotions that are senseless … If it’s just four colour process on a coated sheet, so what? If they’re not sending out a message that’s important to our culture or to our profession, they’re wasting resources.’

This new attitude is now being heeded by more enlightened paper mills, in some cases leading them to re-examine their entire marketing philosophy. Laura Shore, manager of communications at Mohawk Paper Mill, is among those who are questioning previous practice. ‘I’m interested in trying to figure out why a paper promotion exists, what it’s supposed to do,’ she explains. ‘If you’re on the receiving end of these things, it’s basically just a stream of consumer waste that crosses your desk. There are all sorts of elaborate image pieces, but when you line them up, you can’t tell which mill did what.’

Champion International Corporation was one of the first paper companies to address the problem. Guided by Miho (who now teaches at the Art Center College of Design, Pasadena), it began to provide technical information in its promotions, producing documents that transcended ‘whoopidoo graphics’, as Vanderbyl calls it. The next step was for mills to go beyond sales tools with work that proffered new ideas, challenged their audience or offered in-depth information on the subject of design itself. New York Times senior art director Steven Heller and Pushpin Group director Seymour Chwast teamed up to produce one of the first such documents, a series of journals for Mohawk called Design & Style that profiled significant eras in design history.

The series was cancelled after several issues, but it paved the way at Mohawk for documents like Rethinking Design, a current promotion that is more design journal than marketing tool. Edited by Pentagram New York partner Michael Bierut, it includes items such as Bierut’s essay on whether clients are really to blame for inferior design; a critical interview with marketing guru Larry Keely; and a humorous graphic designers’ aptitude test. ‘It’s essentially a journal,’ says Shore, ‘in which people talk about design from several different perspectives. My feeling was that we could be as controversial as we wanted as long as we kept strictly to the subject of design. I didn’t want to cross over into any of the big political issues, though, because it’s not really Mohawk’s place to do so.’

While Mohawk may be reluctant to venture beyond design as a promotion topic, a series of single-issue magazines launched last June for Champion’s Kromekote line deals with a number of dicey subjects. All carry a disclaimer stating that the views expressed are not necessarily those of the mill.

Subjective Reasoning is co-edited by William Drenttel, a president of design firm Drenttel Doyle Partners, and Pentagram partner Paula Scher. The unusual collaboration between Pentagram and Drenttel Doyle, competitors who sit across the street from each other in New York City, is the result of both pushing Champion to do much the same thing at the same time. ‘We were really saying to them in different ways that Kromekote is a very important paper. It’s been around for a long time, and if it’s important, let’s put important things on it. It’s as simple as that,’ Drenttel says.

Subjective Reasoning tackles everything from Europe’s immigration problems to the landmark copyright infringement case Art Rogers vs Jeff Koons, which Drenttel says, is the first time modern art has gone on trial in America. ‘The real point is, all these things are about something. These are not promotions where the designer takes his favourite little collection out of some dusty drawer and publishes the cute things he likes. If we’re going to spend money and swamp designers, we have the responsibility to put something out that’s worth reading.’ Apparently Champion agrees. After producing six issues last year, the mill has committed itself to at least six more.

Another well known, thought-provoking promotional series is the recent Potpourri, by Gilbert Paper Company. In Potpourri, four designers are each given the same topic (anything from freedom of expression to illiteracy) and allowed to produce a piece expressing their feelings on the subject. Cincinnati-based designer Lori Siebert, a typical target for such promotions, says she refers to Potpourri time and again for inspiration. ‘There have been some really strong things to come out of that,’ she remarks. ‘I think they’re powerful both verbally and visually, so they stand out in my mind.’

Approaching the issue of content in a much more visually explosive manner is another Gilbert promotion, Give and Take, designed to introduce the mill’s Esse line to the Australian market. Rick Valicenti, of Thirst, Chicago, developed the piece – the closest any paper promotion has so far come to an artist’s self-portrait – from concept to finish. ‘I had the opportunity to create something that wasn’t trying to be a paper promotion,’ he says. ‘Paper promotions have treated designers like idiots. The paper companies have spent so much money running presses, making paper and mailing these things, they’ve failed to give thought to what it is they’re trying to show.’

By taking such chances, Gilbert’s marketing manager, Su McLoughlin, says the company hopes to align itself clearly with the design community by showing that it understands what design is all about. ‘We practise trying to be an enlightened client and so let the designers take it where they want to take it. I pull the reins as infrequently as possible. It clearly reflects that we understand the design process.’

Still, paper promotions, whether content-oriented, informational or glitzy, must sell the product. Can these mills guarantee their content promotions are doing that, or are they merely image builders? ‘I wish I knew,’ laughs Shore. ‘I’d be surprised if a designer told me they bought paper because of Rethinking Design alone. But what it does is to establish the mill as being in tune with what designers want, need and believe in. So then what you hope is that there are certain companies whom designers feel close to because they feel those companies care about designers.

‘That doesn’t mean designers will always buy our product – they may not ever need that product. But when they’re looking for a product of a type that we sell, designers might be more likely to think about us. “That’s really the best we can hope for.”’

Laurel Harper, editor, How magazine

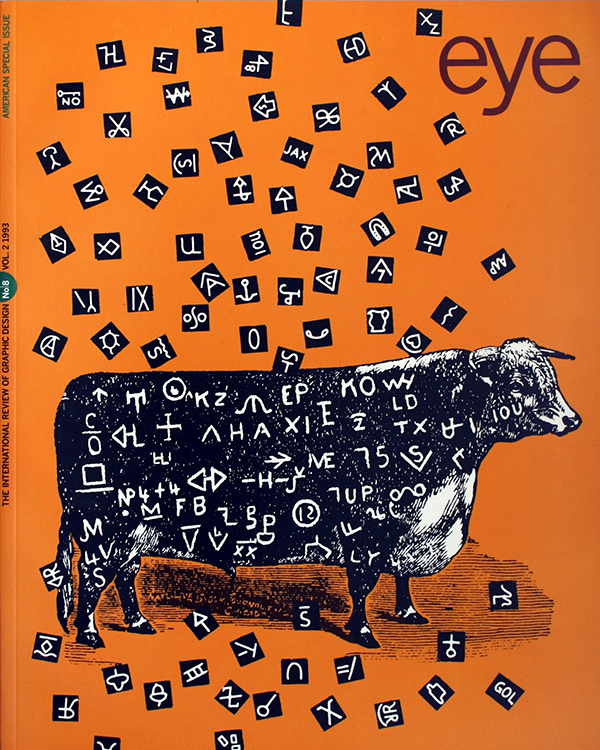

First published in Eye no. 8 vol. 2, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.