Monday, 9:00am

2 July 2012

The art of illumination

Will Burtin, the man who invented infodesign, 1940s – from Eye 82

Born in 1908 in a working-class district of Cologne, nothing about Will Burtin’s childhood suggested that the boy would one day pioneer several fields of graphic design, writes Robert Fripp in Eye 82.As a reluctant altar boy, he spent many early mornings at St Gereon’s Basilica. However, this unhappy experience did confer one lifelong benefit: the basilica’s painted images showed Burtin how design and form effectively conveyed information. At fourteen, he began studying typography in night school while working days for his first employer and mentor, Dr Philippe Knöll. In 1926, Dr Knöll’s typography shop was working overtime to produce text and illustrations for exhibitors at the upcoming international exposition, Düsseldorf’s GeSoLei.

By 1930, Burtin was an independent designer. Business grew with his reputation. His work came to the attention of Joseph Goebbels, the head of the Nazi propaganda ministry. In 1937, after Burtin rebuffed Goebbels’s invitation to head the ministry’s design section, Hitler summoned him to an interview in person. Burtin, and his Jewish wife, Hilde, fled Germany.

Sponsored by Hilde’s first cousin, wind tunnel designer Max Munk, the pair fled to the US, where, within months, he won a major contract from the US Government to create the Federal Works Agency’s exhibition at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Soon after that he was illustrating and designing for Time and Life magazines and The Architectural Forum.

Drafted in wartime to the Office of Strategic Services, Burtin headed a design team charged with a priority project: designing manuals for aerial gunners in bomber crews. Burtin’s clear design cut gunners’ training from six months to six weeks.

The late 1940s marked the apogee for using graphic design in magazines to illustrate technical, scientific and medical practices. The postwar world was new: it had discovered rockets, missiles, atomic bombs, antibiotics, jet engines, insecticide, television and the first computers. As the art director at Fortune magazine (1945-49), Burtin illustrated these emerging technologies for the sophisticated business leaders and readers building a new society on postwar innovation.

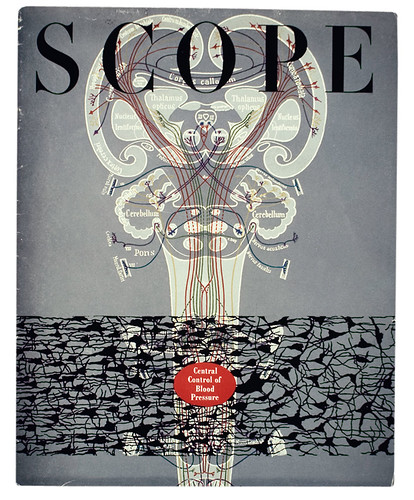

Simultaneously, Burtin took over as art director of Scope magazine (above), the Upjohn Company’s direct mailer to doctors. Reasoning that doctors use their hands to diagnose patients, Burtin responded by combining several different paper stocks in each tactile edition.

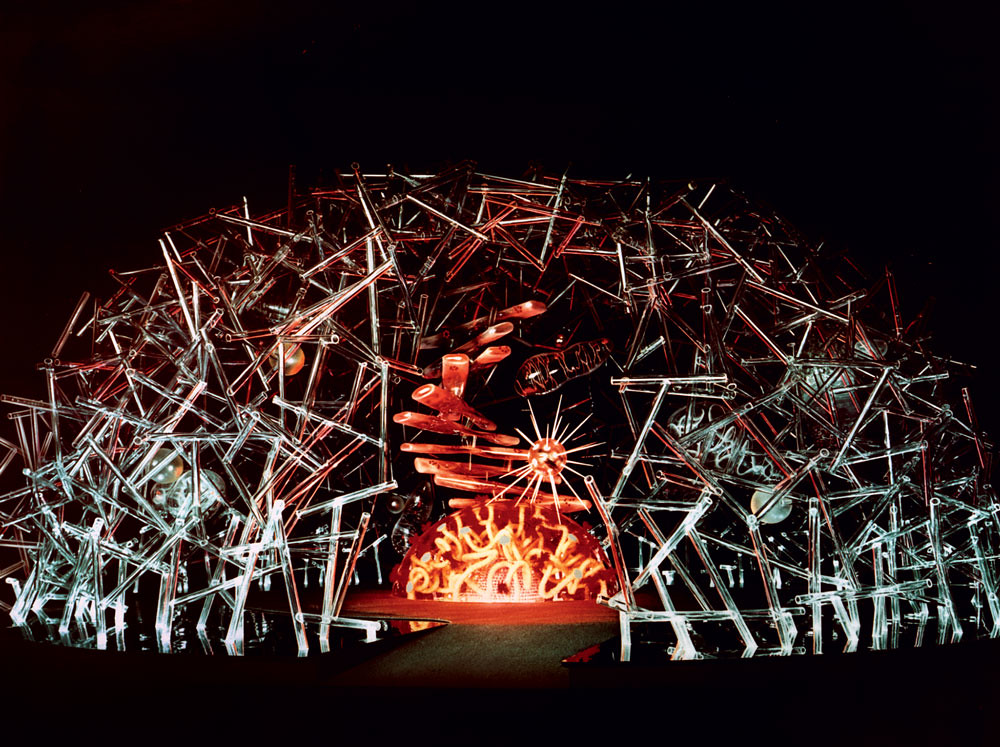

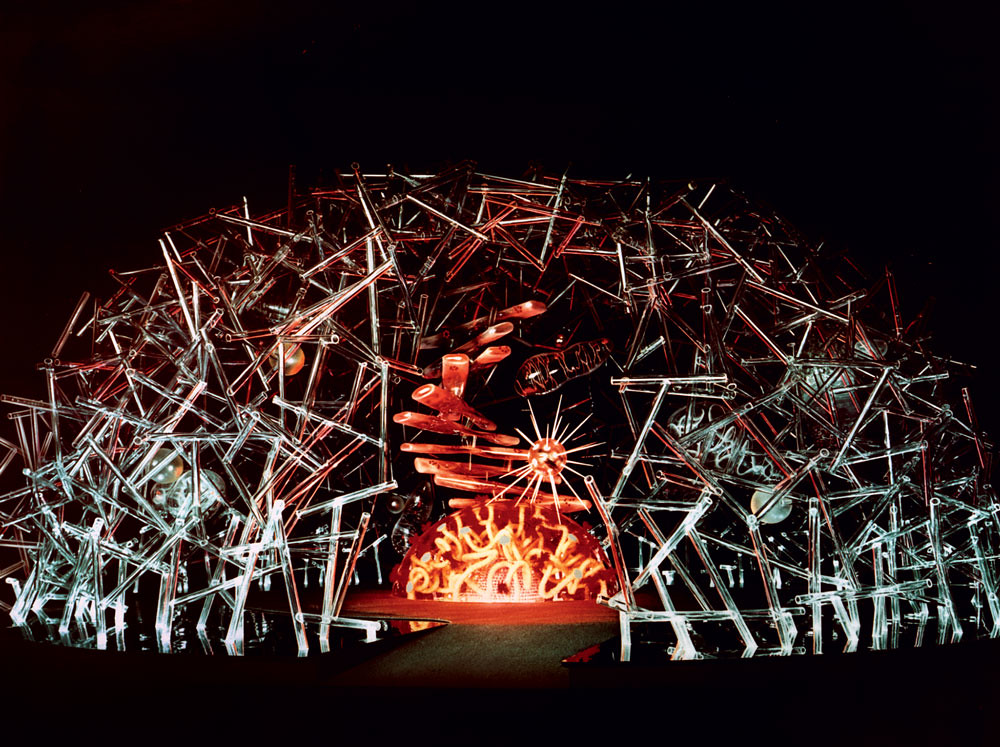

Burtin’s large physical models of biomedical processes for Upjohn – the Cell, the Brain, Metabolism, Genes in Action and Defense of Life – stand out. Often, Burtin’s work put into understandable form what scientists had previously been unable to visualise. His models attracted widespread attention and were featured in international publications and television specials.

Thus the man with little formal schooling would be instructed in science by the likes of Albert Einstein (prior to illustrating one of the first printed articles on nuclear power), top neurologist Wilder Penfield and futurist Buckminster Fuller. He translated their information in turn into visually comprehensible images.

Top and above: two views of Upjohn’s human Cell, built to open the 1958 convention of the American Medical Association (AMA). Photos © Ezra Stoller.

From ‘The art of illumination’, another part of ‘The graphic power of knowledge’ published in Eye no. 82 vol. 21, 2012.

See also, ‘Founding father of infodesign’ by Simon Esterson in Eye 82.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. Eye 82 is out now, and you can browse a visual sampler at Eye before You Buy. Eye 83 is on press any moment.