Thursday, 8:00am

10 September 2015

Eroticism with existential overtones

Mirko Ilić

Dragan S. Stefanović

Čedo Pocrnić

Mirsad Saric

Design history

Graphic design

Music design

Visual culture

In the former Yugoslavia, record covers briefly delivered a ‘disco message’ of inclusion, emancipation and hedonism. By Zeljko Luketic

Will there be a disco ball? Or at least roller-skates? Those were the two most common questions I heard while preparing a series of ‘Socialist Disco Culture’ exhibitions, writes Zeljko Luketic.

The shows began in late May in Lotrscak Tower Gallery in Zagreb and continued in July in HDD (the Croatian Designers Association Gallery) a few blocks away.

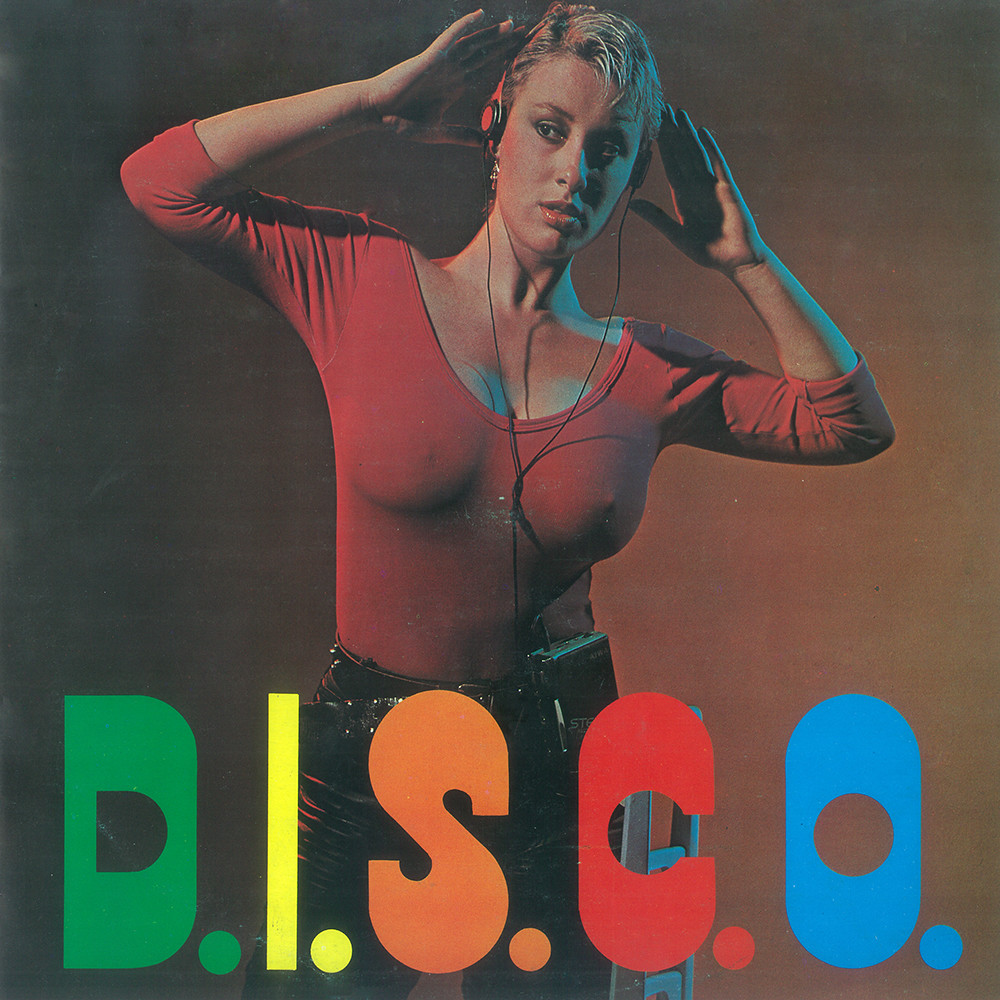

Oliver Mandić, Probaj Me, 1981 (12-inch).

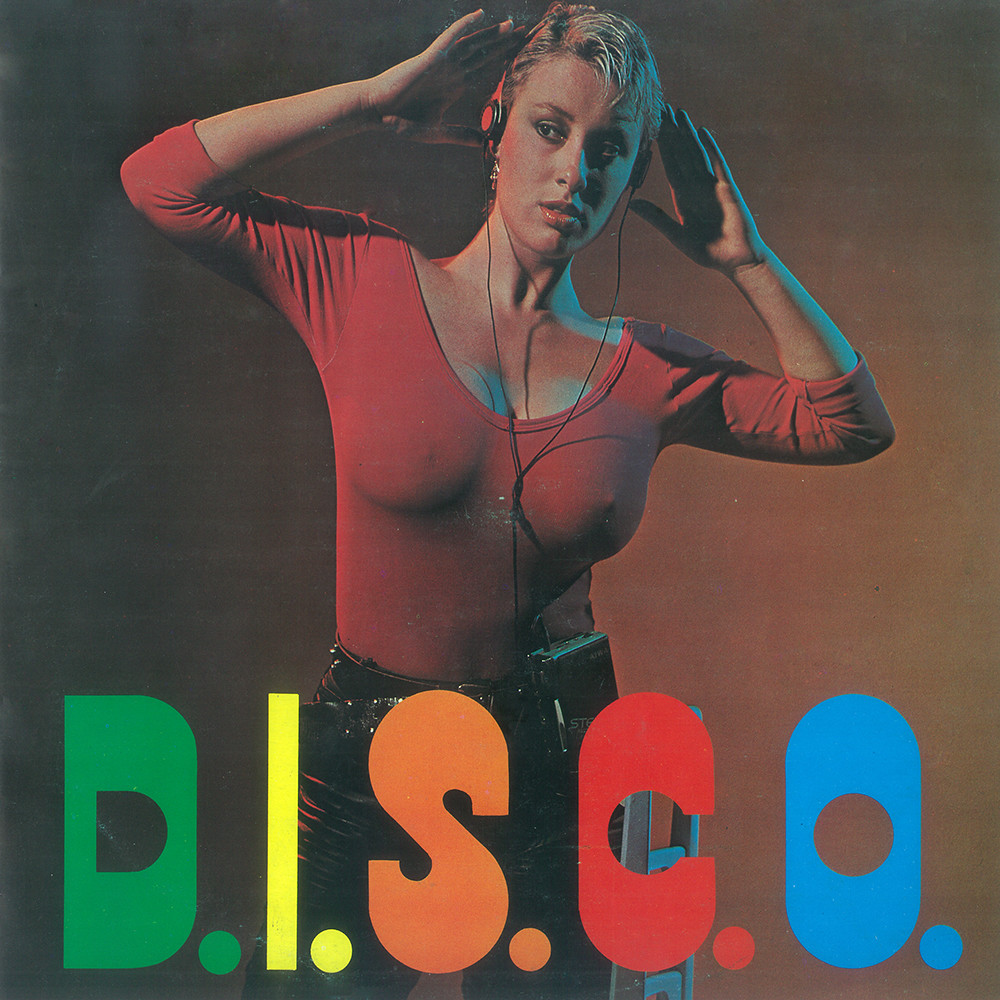

Top: D.I.S.C.O., 1983 (12-inch).

No, I replied, there won’t be any of those signs – hated and loved in equal parts – of disco culture. Emerging subcultures such as punk and new wave may have hated it; old rockers and proggers couldn’t stand the glitz, the costumes and the beat; but funk and jazz instrumentalists and pop singers embraced, making it most commercially visible genre of the 1977-83 period in the geopolitical experiment formerly known as Yugoslavia.

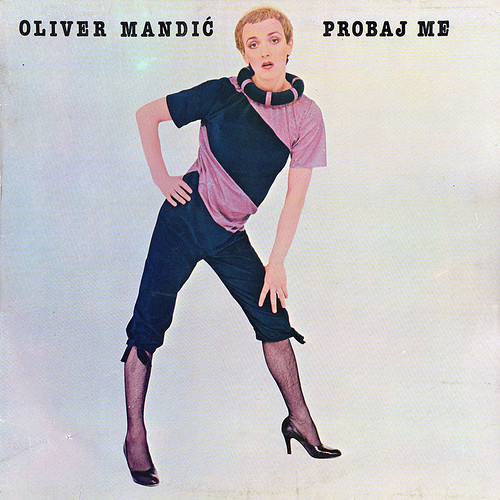

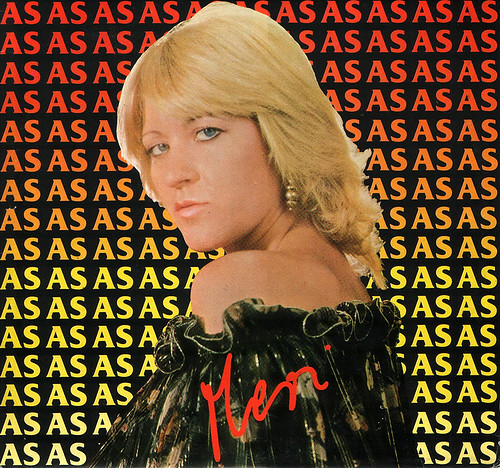

Meri Cetinic, AS, designed by Mirko Ilić, 1982 (12-inch).

Vesna Kartuš, Priđi mi bliže, 1982 (12-inch).

The impact of disco on Yugoslavia lasted much longer than in the West. The genre remained popular until the mid-1980s in lively dance competitions organised by popular clubs and music magazines. Record companies issued the back catalogue of the Village People and some fake disco ‘compilations’ of cover versions recorded with unknown studio musicians. Disco aficionados chose them for their cover art.

The concept of the ‘Socialist Disco Culture 1977-1983’ exhibitions was intended not as nostalgia porn but to question the impact of the genre on aspects of Yugoslav society. The black-framed artefacts – seven- and twelve-inch record sleeves – were placed in minimalist museum settings: Lotrscak Tower and HDD Gallery. The main ideas of the project had to be clearly readable.

The first exhibition, subtitled ‘Influences, Role Models and Innovators’, attempted to locate the positive implications of Disco. The show mapped the main emancipatory elements, with documents revealing the liberating effect of the genre with regard to female and male sexuality. Disco introduced clubbing as we know it today. The first dance competitions with the practice of including national and sexual ethnicities and minorities took place. One article described Disco as ‘eroticism with existential overtones’ – an accurate impression of Disco in the former Yugoslavia.

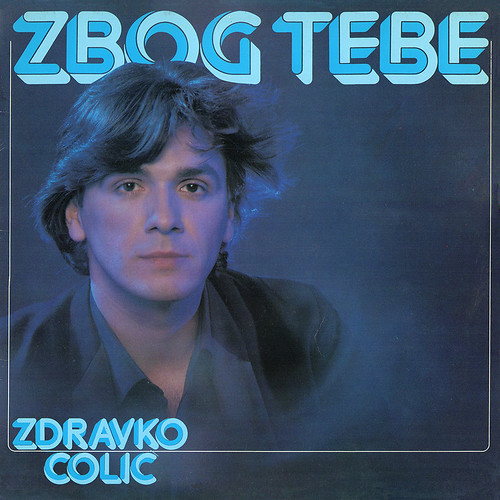

Zdravko Colic, Zbog Tebe, 1980 (12-inch).

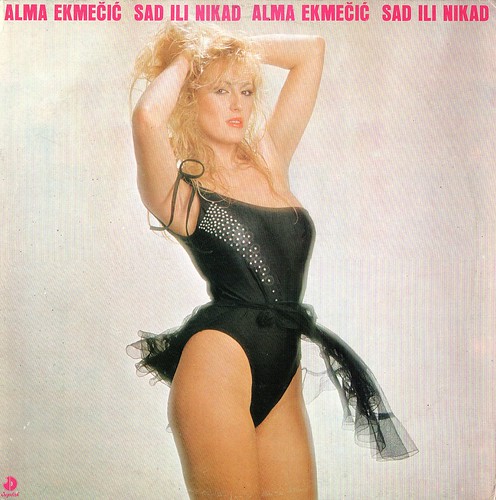

Alma Ekmečić, Sad Ili Nikad, 1984 (12-inch).

The second exhibition (in the HDD) was subtitled ‘The Visual Language Of (Socialist) Disco’. The record covers were displayed as the main tool of delivering ‘a disco message’ that showed different ways of communicating the ideology of the movement – sexual emancipation, the inclusion of minorities, the modernity of the clubs’ ambience plus socially accentuated hedonism. Disco was a kind of protest against socialistic norms.

Ivo Lesić, Ona voli disko klub, designed by Čedo Pocrnić (7-inch), 1980.

An LP, single or cassette cover had to deliver a message in the shortest possible time, and the unsubtle Disco aesthetic was an efficient advertising tool. Some design were more successful than others which were unquestioningly formulaic. Disco’s visual clichés included dance floors, bright reflectors, and disco fashion – tight, shiny costumes revealing more than they concealed. Two hundred hand-picked record covers, designed by individuals such as Mirko Ilic, Boris Ljubicic, Dragan S. Stefanovic and Ivan Ivezic, were grouped into subthemes: famous Yugoslav disco artists and their visual language; local editions of international artists’ records; and the dominance of seven-inch singles in socialist record publishing.

The Socialist Disco Culture concept does not finish here. The Croatian label Fox & His Friends is planning the release of a vinyl LP of the best moments of Yugoslav disco.

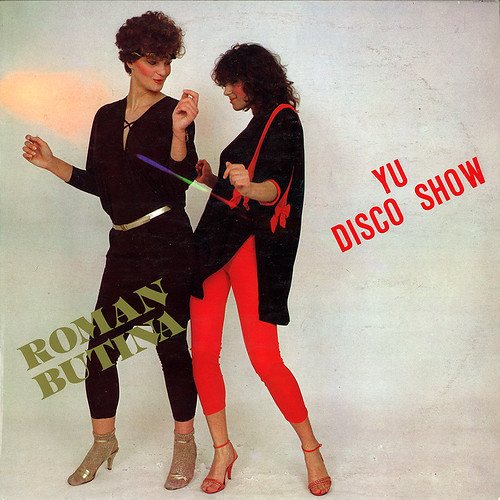

Roman Butina, Yu Disco Show, 1982 (12-inch).

Roman Butina, Disco Show 3, designed by Drazen Kalenic (12-inch).

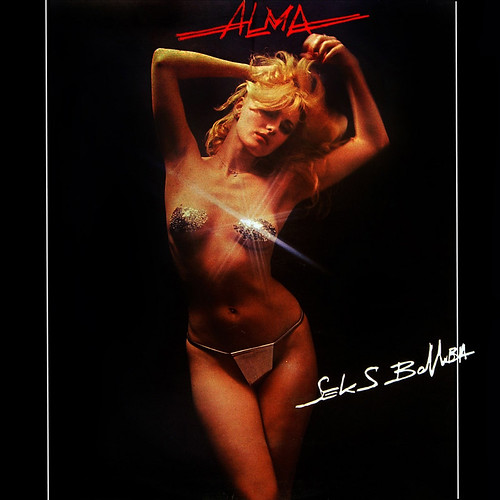

Alma Ekmečić, Seks Bomba, designed by Dragan S. Stefanović, 1982 (12-inch).

Mirzino Jato, Normalna stvar, designed by Mirsad Saric, 1979 (7-inch).

Zeljko Luketic, critic and curator, Zagreb, Croatia

Special thanks to Rick Poynor for his help in publishing this article.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.