Friday, 2:54pm

11 May 2012

Full tilt

Glass & Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach liberates the space-time continuum.

Though I missed the UK premiere* of Einstein on the Beach by Robert Wilson and Philip Glass (nearly 36 years after its first performance in Avignon), reports John L. Walters, the performance I witnessed ran flawlessly without a break, clocking in around four hours 20 minutes, and earning a standing ovation from the packed house.

Top and below: photographs of Barbican Theatre production of Einstein on the Beach © Lucie Jansch, 2012.

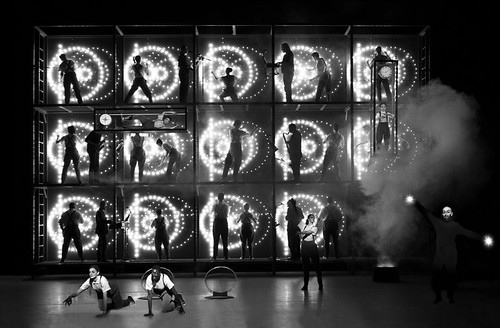

Clocks, or time, could be said to be an overarching preoccupation of Einstein on the Beach. Performers wear big wristwatches; clock faces descend, ascend and mutate (above); and the cast members chant number sequences as part of Glass’s relentless, hypnotic score for a large onstage chorus and a small instrumental ensemble. Both sound and visuals force us to change our perception of time: the show comprises a series of slowly metamorphosing tableaux rather than a sequence of dramatic scenes: there’s no plot, and the libretto (by several writers, including Einstein’s choreographer Lucinda Childs) is of varying relevance. Some of the words are a kind of audio ‘lorem ipsum’ that fleshes out Wilson’s artfully constructed space-time.

Things change – slowly – all the time, as they do when you watch a seascape or a digital installation. There are the details of small, rapid gestures and exaggerated expressions on the faces of the performers, plus the lighting and the flat images (a train, and in the final scene a bus, above) that trundle on and off stage at a glacial pace. Much of it feels like early Modernism, with a dash of German expressionism. The colour scheme – mainly black, white, red and multiple shades of grey – might have come straight from the Bauhaus show upstairs. (The make-up and props wouldn’t have been too out of place at the celebrated Dessau ‘Metal Party’.)

Lucinda Childs’ choreography in the two dance sections are in complete contrast to the intense, fidgety movements of the white-faced performers in the two ‘Trial’ scenes. The dancers’ skipping movements, light and fleet, add air to the dense machinery of Glass’s hurdy-gurdy-like orchestration of voice, woodwinds, organ and violin.

In the most abstract section, known as ‘Bed’, we’re presented with a single graphic image: a solid rectangle, white out of black. This thick horizontal typographic rule moves through 90 degrees into a vertical position, like an kinetic Dan Flavin light sculpture. Then the solo organ in the pit is joined by mezzo-soprano Hai-Ting Chinn, who adds her voice to the solo organ, and the white obelisk rises slowly until it is out of sight.

Einstein on the Beach is a spectacle. The setting, the theatre auditorium, the operatic scale, the intensity of Glass’s additive and cyclical melodic patterns, like fractal five-finger exercises, all require us to look. And to keep looking and listening for a very long time. Kurt Munkacsi’s amplified sound design, still controversial within classical music circles, is a crucial part of Glass’s unstoppable sonic assault, rhythmic, intense and rock-like without using any rhythm section instruments.

This approach is at its most extreme in the ‘Spaceship’ section, a cacophonous matrix of voices, movement, colour and full tilt playing from the (now) onstage ensemble. A grid of flashing lights creates random patterns and glyphs, and transparent elevators (containing writhing captives) glide horizontally and vertically (above).

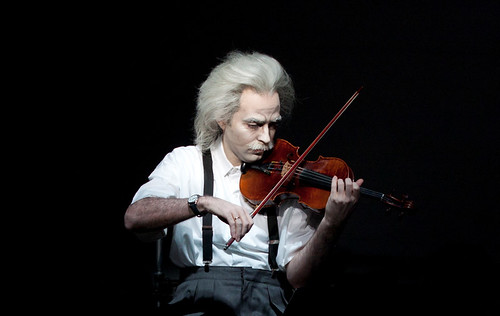

Then a screen descends, and violinist Antoine Silverman, a shock-headed Einstein figure (above), is isolated against an indigo curtain while a tiny model spaceship creeps slowly up a wire.

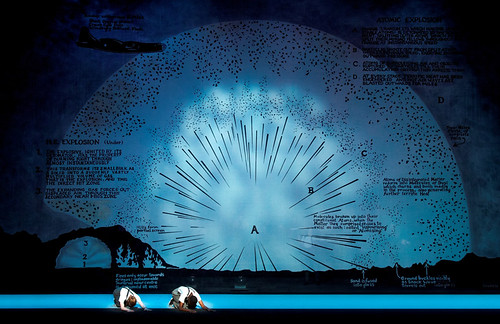

The screen shoots up again. And then another drops down to show a quasi-scientific diagram of an ‘Atomic Explosion’ (below), with laconic captions such as ‘Sand is fused into glass’.

The demands that Einstein on the Beach makes upon an audience (to behold a spectacle rather than follow a story) may be a reason why even sympathetic music critics feel irritated by its sprawling contents. If it is an opera, it is one for which there is little precedent or parallel.

The Barbican production’s adoption of its original design and staging has been regarded as ‘dated’ in some quarters. In conventional opera, the director and designer often impose fresh visual concepts or moods upon an existing work with a pre-existing musical and dramatic character – The Magic Flute, say, or Jenůfa. By contrast, Einstein on the Beach is best approached as a work defined by Wilson’s visual and dramatic framework from the beginning.

Stanley Kubrick, (in conversation with sci-fi writer Brian Aldiss) once said, ‘… forget about narrative … all you need for a movie are six or eight non-submersible units.’ (2001, based upon a short story, is a good example of this.) Similarly, much instrumental music works in this way – nobody expects Coltrane’s A Love Supreme or Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms to tell much of a story, even though both have explicit, easily graspable structures. Pop hits often hang on such moments: a drum fill, a catchy hook, a singer’s scream.

So you can enjoy Einstein on the Beach as a predominantly visual work that packs dancing, spoken word, acting, singing, mime and music into the time-based structure of film or music theatre. Even though its ambitions might have been as an operatic gesamtkunstwerk, its reality may lie closer to the world of installation and performance art. Many experimental musicians of Glass’s time (including Steve Reich and Gavin Bryars) found their original audiences in galleries and art colleges rather than music venues.

But Einstein is also much more than Wilson’s vision, because it benefits from an unusually close and effective degree of collaboration with composer and choreographer. ‘We put together the opera the way an architect would build a building,’ wrote Wilson. ‘The structure of the music was completely interwoven with the stage action and with the lighting. Everything was all of a piece.’

Einstein on the Beach didn’t just spring from a few downtown lunches – it emerged from a lively international scene of experimental, transdisciplinary work that dispensed with conventional barriers between crafts and genres, and subverted technology (however crude) to its own ends. It is now possible to appreciate Einstein in the 21st-century context of code-based multimedia, where technology allows artists to combine sound, vision and movement with a freedom and virtuosity hardly dreamed of at that time.

Yet much of what we see and hear is constrained by small screens and loudspeakers. Perhaps the Barbican show will encourage suceeding generations of makers and producers to think big. Despite its age, Einstein on the Beach – decades before the great work made by UVA, Karsten Schmidt, Ryoji Ikeda and Universal Everything – provides a lesson in making powerful, affecting multimedia in its creators’ own terms.

All photographs copyright Lucie Jansch, 2012, courtesy of Barbican Centre press office.

Further 2012 performancesof EOTB take place in Toronto, Brooklyn, Berkeley and Mexico City, followed by Amsterdam and Hong Kong in 2013. Details at Pomegranate Arts site.

John’s Guardian column about Philip Glass’s music for The Hours (and other things)

*The UK premiere did not go smoothly. Some of the onstage mechanisms (moving gantries and glass boxes) did not work and there was an unplanned interval. (A post-show altercation between a critic and an allegedly snap-happy Bianca Jagger prompted much online chatter.)

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. Eye 82 is out now – you can browse a visual sampler at Eye before you buy on Issuu.