Thursday, 6:00pm

6 August 2015

The illusion of artivism

Abake

Assume Vivid Astro Focus

Discoteca Flaming Star

Etcétera

Improv Everywhere

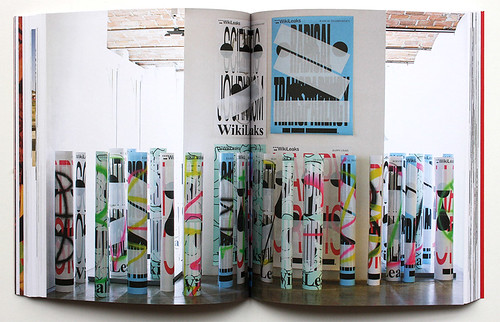

Metahaven

Project Projects

Société Réaliste

Critical path

Photography

Reviews

Visual culture

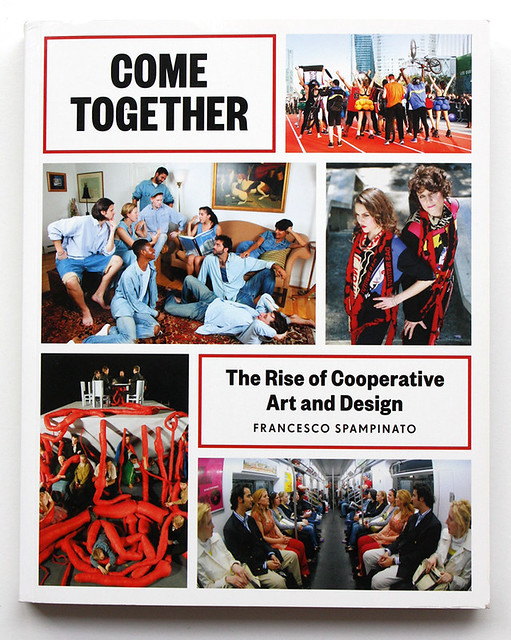

Come Together: The Rise of Cooperative Art and Design

By Francesco Spampinato. Princeton Architectural Press, $35This new book assembles a visually engaging patchwork of contemporary art and design collectives. Review by Alice Butler

A blonde woman in a cream coat sits next to a man in a navy jacket. They are on the subway, gazing at their mirror images, but there is no mirror, writes Alice Butler.

This is a photographic document of the live performance Human Mirror, choreographed in 2008 by the New York-based art collective Improv Everywhere, using identical twins to construct the mirror illusion.

Cover of Come Together. Design: Paul Wagner.

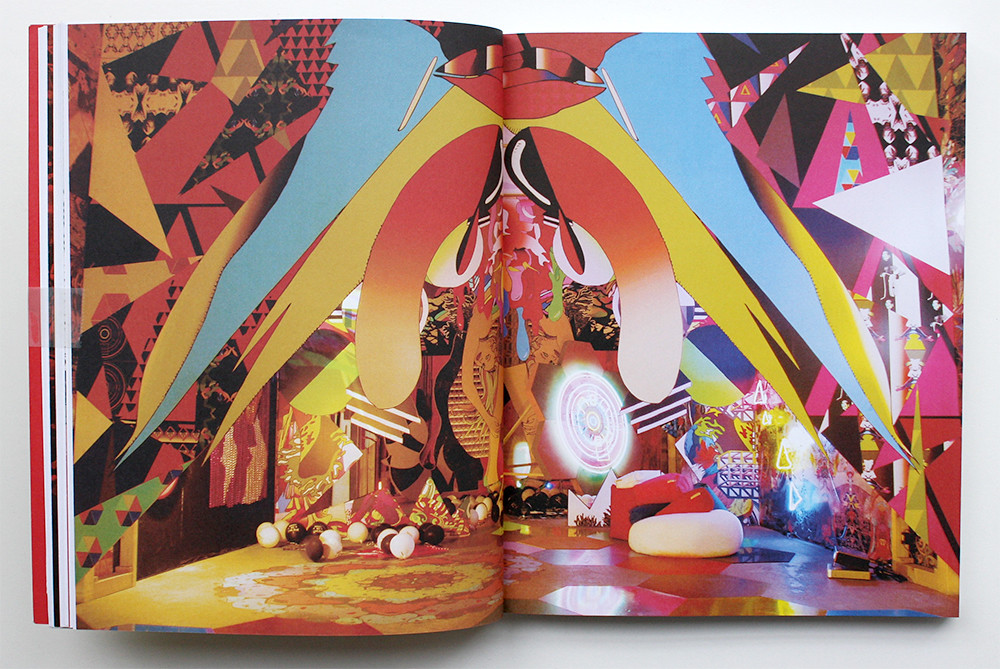

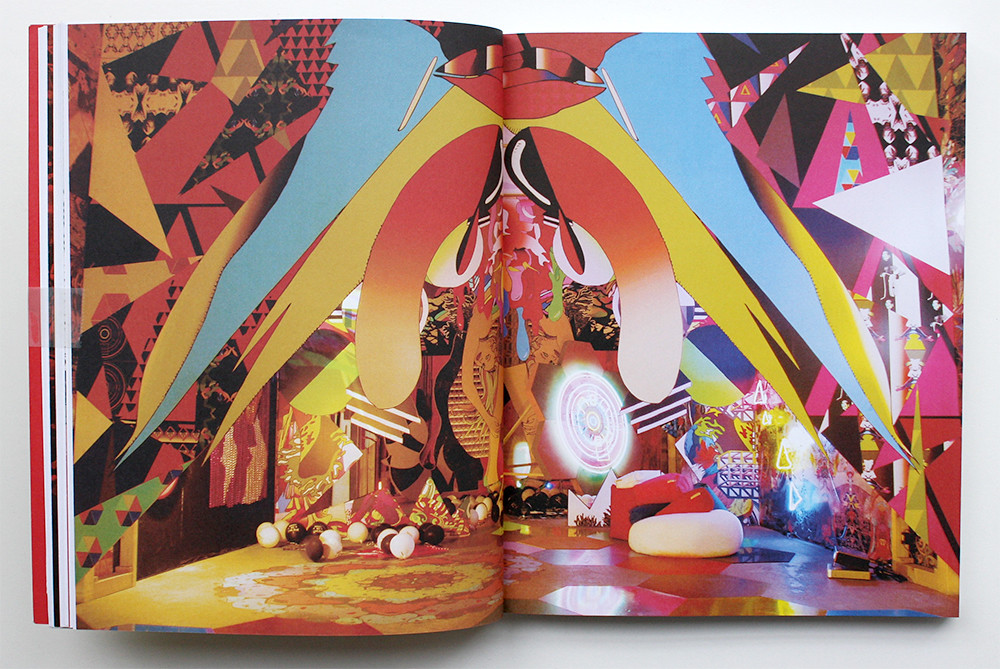

Top: Spread. Absorb Viral Attack Fantasy, Installation, Hiromi Yoshii, Tokyo, 2006, from the chapter about Assume Vivid Astro Focus (AVAF), Eli Sudbrack and Christophe Hamaide-Pierson.

But although the photograph is documentary, it is also mediated: the liveness of the original performance is lost in its communication. Sometimes a photograph isn’t enough: this image, one of five pictures on the front cover of Francesco Spampinato’s Come Together: The Rise of Cooperative Design is not explained in the book’s profile of the collective.

The image floats, with little context given for the participatory nature of the performance, only the predictable words of the group’s leader: ‘The internet has given us the power to work with crowds in new and exciting ways.’ The reliability of Spampinato’s research is indeterminate. He points towards other sources: ‘If you wish to know more about any of them, explore the websites or publications suggested that precede each of this book’s interviews.’

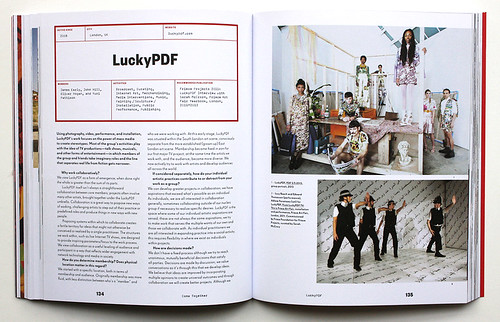

Spread from Come Together, 2015. Lucky PDF.

Come Together uses the form of the interview to investigate the proliferation of collective production in the spheres of visual art, design and performance. We meet Lucky PDF, London-based makers of TV parodies; Fallen Fruit, a Los Angeles group running culinary workshops; Assume Vivid Astro Focus, organisers of carnivalesque happenings in New York, São Paulo and Paris; and 38 more collectives. Co-operative art and design embodies the ‘rhizome’, the philosophical concept developed by Deleuze and Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus (1980), whereby critical thought is rendered as a map of multiple entry-points and connections, resisting narrative and chronology. Open-ended, polymorphous and non-hierarchical (much like the rhizomatic internet), collective art-making resists the linear structures of society, and the concept of the individual ‘artist-genius’.

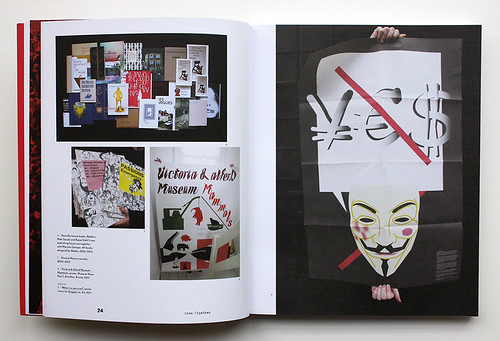

Spreads from Come Together, 2015. Right: Åbäke.

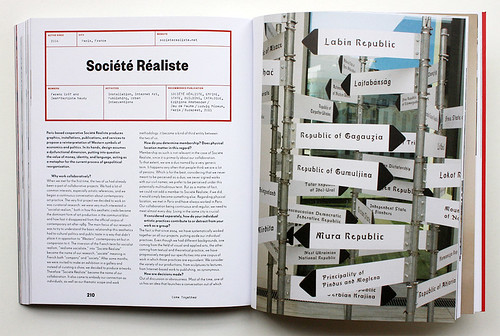

Below right: Société Réaliste.

If only the book lived up to these concepts. While a useful resource for art and architecture students, and a visually engaging patchwork of performance and practice, the book rarely goes beyond the ‘image’ of immaterial labour. The introduction name-checks a number of collectives, with little analysis of the social or political effects of their practice. I am left feeling that Spampinato’s position that ‘borrowing strategies and symbols from mass media, the global market, and the entertainment industry, these collectives unravel and overthrow social, political and cultural power structures’ is not only generalised, but also unsupported by evidence. Likewise, his naff neologism ‘artivism’ is never interrogated.

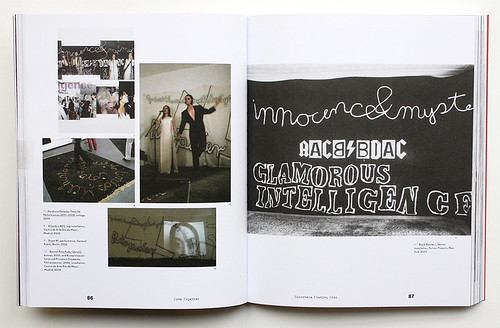

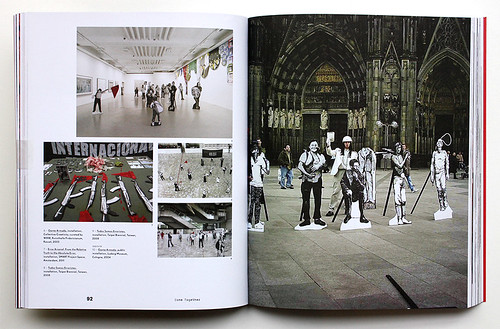

Spreads from Come Together, 2015.

Right: Discoteca Flaming Star. Below right: Etcétera.

The main problem with this interview anthology is the author’s formal strategy. The interview, which is collaborative and discursive, should be the most appropriate form for a discussion of collective art-making, but artists are often so bad at talking about their own work: clichés abound, as in the spaced-out words of a member of the Parisian fashion collective Andrea Crews: ‘…we are building something that is not a fashion brand, but plays with that idea! We are “happy” activists.’ It is not only in the collectives’ answers that one finds sameness; Spampinato’s questions use identikit phrasing for each case study, regardless of location, medium or motive. Instead of being a testing methodology, this is the book’s main failure: it groups these groups together, refusing to pick apart the permutations that define them.

Alice Butler, writer, London

Spreads from Come Together, 2015. Right: Project Projects (see Eye 89).

Below right: Metahaven. Islands in the Cloud, installation, MoMA PS1, New York, 2013.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.