Thursday, 8:59am

17 January 2013

A dentist’s unerring eye

various designers

anonymous designers

Walter Schnackenberg

Jules de Praetere

Design history

Graphic design

Posters

Dr Hans Sachs was the poster aficionado who launched Das Plakat. By Graham Twemlow

Graham Twemlow writes: A large part of the Hans Sachs poster collection is about to be sold off at auction (see ‘Back on the market’). Born in Breslau, Germany in 1881, Dr Sachs began collecting posters at the end of the nineteenth century while he was training to become a chemist (he later turned to dentistry).

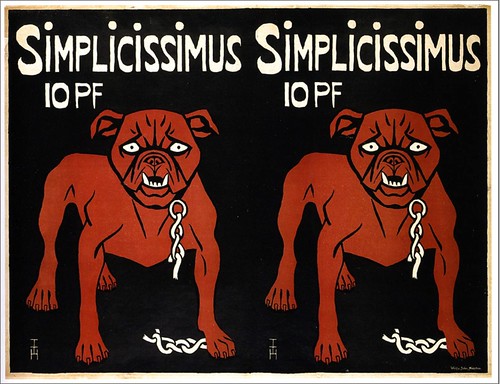

Many of the early posters he collected were, unsurprisingly, French – or at least produced in France. In 1897 the noted German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe claimed that German posters could not be compared to their French counterparts stating that ‘… the poster as conceived in France does not exist [in Germany]’. With an unerring eye Sachs collected the best – acquiring posters by Toulouse-Lautrec, Jules Chéret, Alphonse Mucha, Théophile Steinlen and Pierre Bonnard. One outstanding poster from 1890s Germany he did obtain, however, was a copy of Thomas Theodor Heine’s hard-hitting caricature-style poster advertising the satirical magazine Simplicissimus.

(This poster was to become the test case item that ruled in Peter Sachs’s favour during a protracted series of court cases culminating in the posters’ return to the Sachs family.)

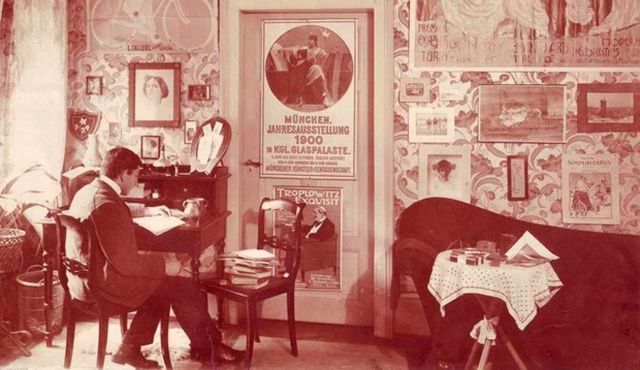

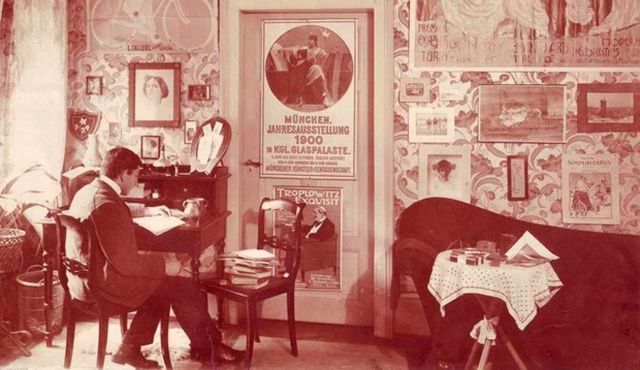

Top: Hans Sachs in his study, ca. 1902. Image courtesy of the Sachs Family.

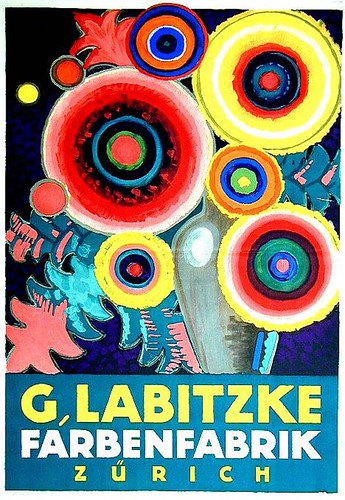

Right: Jules de Praetere, G. Labitzke Fahrenfabrik, poster, 1916. The explosion of colour, symbolising the vibrant shades of paint available from G. Labitzke is redolent of, but predates Sonia Delaunay’s vivid textiles of the 1920s. Image courtesy of the Sachs Family.

Although Sachs established a successful dentistry practice, poster collecting became his passion. In 1905 he formed a Society of Friends of the Poster (Verein der Plakat Freunde) and in 1910 launched a magazine, Das Plakat, devoted to celebrating the poster as an artform. He began to catalogue his collection using a complex handwritten cross-referencing card index system. In 1914 he staged a major poster exhibition in Leipzig that featured 700 of his posters.

By the outbreak of the First World War Sachs had amassed a collection of 3500 posters – this rose to 12,500 by the mid 1920s. In addition he also took an interest in everyday graphic ephemera – covers of periodicals, postcards, theatre programmes, brochures – remarking that future cultural and art historians might find that commonplace printed items such as these would say more about German taste of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries than fine art and architecture. By the 1930s this collection alone had grown to 18,000 items.

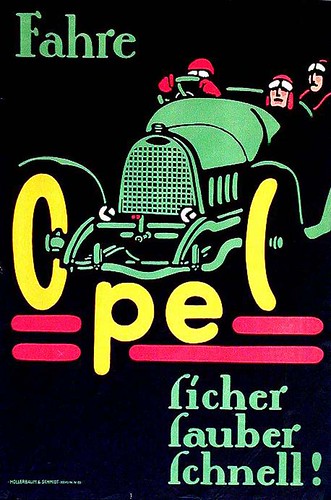

Artist unknown, Opel, poster produced by Hollerbaum & Schmidt, the renowned Berlin printing company, ca. 1913 (Lot 167). The brilliant way in which the artist has formed an ‘l’ from half a tyre ranks high beside the better-known Hans Rudi Erdt posters for the car company. Image courtesy of the Sachs Family.

In 1938 Sachs collection became under increasing scrutiny in Nazi Germany. In November a new law was introduced banning the possession of political printed matter. The Gestapo immediately ‘confiscated’ Sachs’s complete collection of posters, graphic ephemera and his detailed card index system. Sachs was arrested and taken to a concentration camp but his wife was able to secure his release on the promise they would leave the country. The Sachs family fled to America where Dr Sachs was able to continue with his dentistry practice.

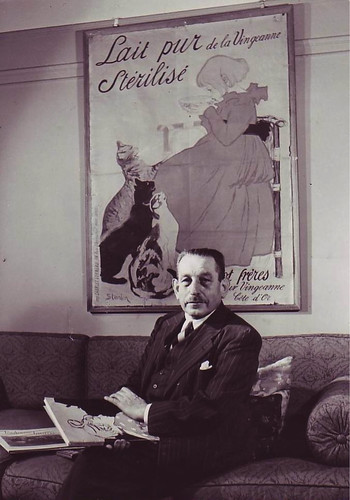

Hans Sachs in New York. The poster in the background is Théophile Steinlen, Lait pur Sterilisé de la Vingeanne, 1894. Photograph reproduced with permission of the Sachs family.

He took with him a collection of thirty-one Toulouse-Lautrec posters (he had managed to hide these away before the Gestapo seizure) to help pay his way – although in financial desperation he sold them for a mere $500. In later life he presumed that the collection had been destroyed, but in 1996 he discovered that some of the posters may have been saved, then residing in the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin. He died in 1974 without seeing his posters again.

Thomas Theodor Heine, Simplicissimus 10PF, poster, 1896.

In 1991 the German resitution laws were enacted allowing items looted by the Gestapo in Nazi Germany to be returned to their original owners. Steven Heller’s article (‘Repossession’) in Eye 74 documents the process that Dr Sachs’ son Peter took to ensure reparation of his father’s collection. Although Peter Sachs won a test case (claiming ownership of one poster – Heine’s Simplicissimus poster, above), the Deutsches Historisches Museum (where the collection then resided) appealed against the ruling stating that Hans Sachs had never lost ownership. A further two years of claims and counterclaims took place until, in March 2012, the Museum was ordered to return the collection of 4344 posters. The whereabouts of the remaining 8000 posters and the graphic ephemera items is unknown, presumably destroyed. At the end of October 2012 these posters arrived in New York.

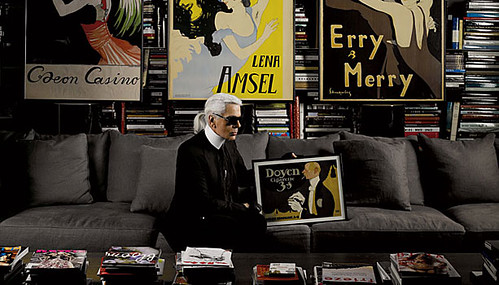

German-born fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld has a collection of posters by Walter Schnackenberg’s (1880-1961), a designer favoured by Sachs.

The Hans Sachs Poster Collection (auction one of three), Guernsey’s, New York, 18 > 20 January 2013.

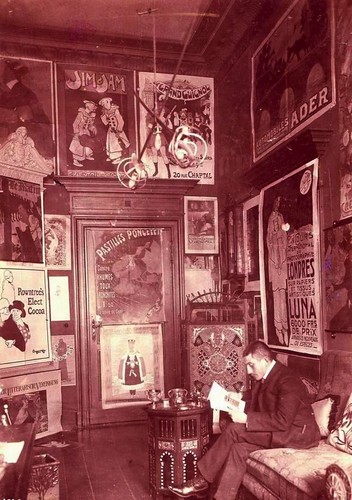

Hans Sachs surrounded by some of his posters, ca 1904.

Among those identifiable are posters by Jules Chéret (Pastilles Poncelet 1896); Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Le Matin, 1893); The Beggartaffs (Rowntree’s Elect Cocoa, 1895); Jules Alexandre Grün (Le Grand Guignol, 1897); Georges Meunier (Automobiles Ader, 1903).

Photograph reproduced with permission of the Sachs family.

See also ‘Back on the market’ by Graham Twemlow on the Eye blog.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 84 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.