Thursday, 9:00am

20 February 2014

Caught snapping

An exhibition of photographs by Andy Warhol, William S. Burroughs and David Lynch provides some fresh insights into their work

When you tire of the detritus of uncensored commodity that is London’s Oxford Street, you can escape through a thin slit of an alleyway and find yourself at The Photographers’ Gallery, writes Colin Davies.

The converted Edwardian building is topped with North’s crisp branding; never has Akzidenz Grotesk been so perfectly framed. The gallery is currently showing work by three artists – Andy Warhol, William Burroughs and David Lynch – who are not predominantly known for their photographic works. Their images demonstrates the way avant-garde artists sniff the air and track a path long before others follow – in film-making, writing and art.

Each artist has a floor to himself, starting with Warhol and rising up to Lynch.

Andy Warhol, Young Man holding a Glass, 1976 – 1986. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts,

Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS,

London. Courtesy Bischofberger Collection, Switzerland.

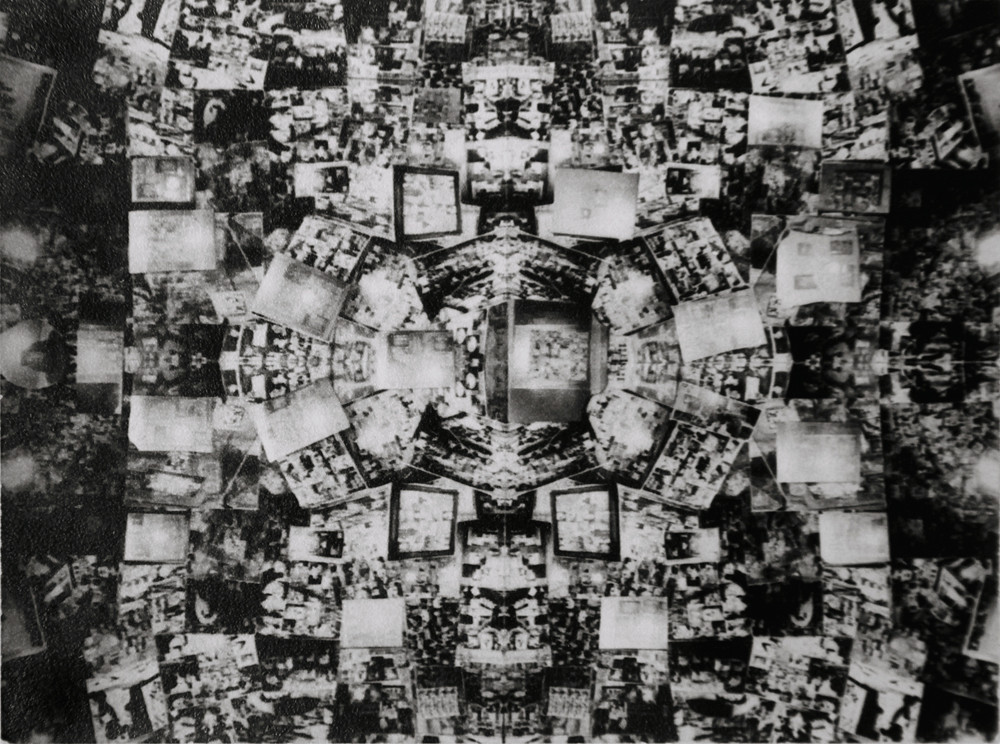

Top: William Burroughs and Ian Sommerville, Infinity, (Beat Hotel), Paris, 1962. © Estate of William S. Burroughs. Courtesy Private Collection, London.

As a boy, Andy Warhol was seduced by the glamour of photography and he explored the medium throughout his career. But as technology became increasingly portable, his images became intimate snapshots rather than glamorous evocations and later, reproductions. The Warhol photographs are from the ten years or so before his death and represent his final flirtation with the medium.

The Warhol display is beautifully curated; the familiar typologies of sequential images pivot around smaller collections of snapshots. The sewn-together images of License Plate on Front of Truck, 1976-1987, demonstrate the rhythms and dynamics created by the use of repetition and sequencing and mimics the layered experiences of urban living. This experience is further underlined in the sequence Good Humor Ice Cream, ca. 1976-1987, depicting vernacular livery.

A few years after the Warhol work on display here, Octavo magazine filled five of its pages with embossed license plates. Here, reproduced solely as a coding system with no life, no movement, the number plates – such a basic element of the visual rhetoric of urban life – become barren artifacts. The Warhol images remind us that typography (and design in general) when removed from its context can shrivel on the stem.

Exhibition photograph by Colin Davies.

With images of the homeless, a gay pride march, and commodity spectacle like the advert for ‘Eyewitness News’, the work reflects Warhol as political savant. Seen in the context of Reaganism, and the rise of the religious right, School Bus, Gay Head, 1981, snapped in the same year as Reagan’s first inauguration resonates beyond simple double entendre.

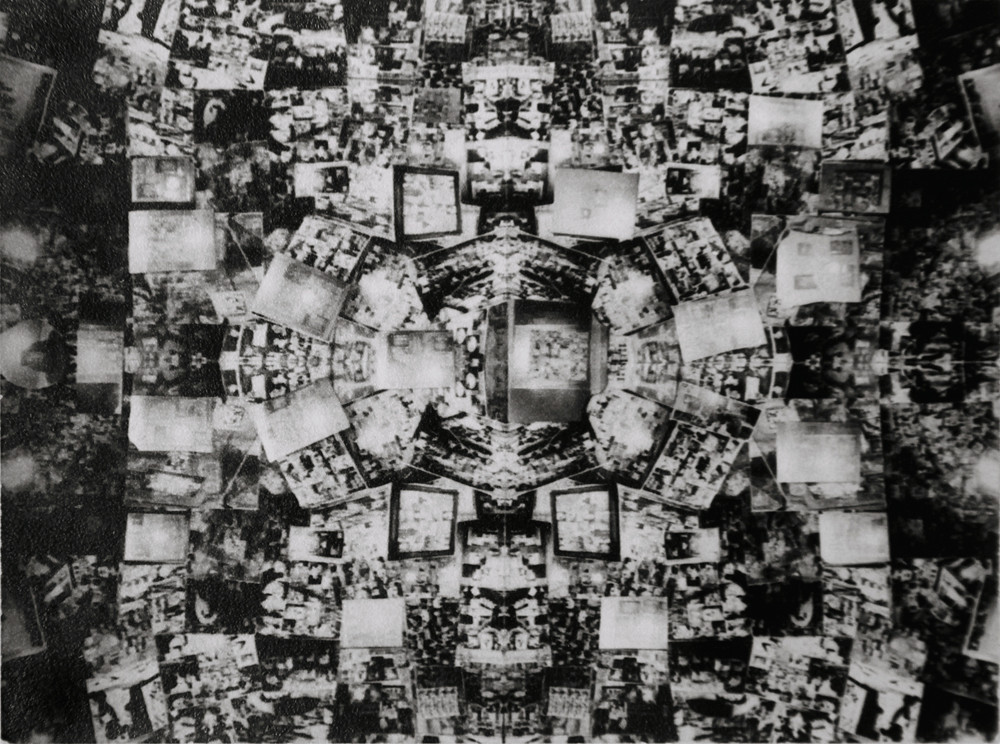

William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, Untitled, 1965. © Estate of William S. Burroughs. Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Up a level, and back a couple of decades you can witness in the middle gallery how William S. Burroughs mischievously snapped at the heels of the fast imploding 1960s. The camera allowed him to cut up time to sequence urban existence. The seven-column grid of images The Series: New York Car Accident captures the essence of Burroughs’ love of the snapshot – through sequence, editing and storytelling – and his ability to unfold narratives.

Untitled, 1965, by Burroughs and English-born artist Brion Gysin, combines a grid with montage and photographic cut-ups. It is cinematic in its layout – a Frankenstein monster of Robert Rauschenberg and Josef Müller-Brockmann – and is a simple but riveting image for its possible influences on design.

Equally influential are Burroughs’ experiments in the series: Infinity Pictures. Here he experiments to capture years of snapshots into a single frame or sequence, which in turn are layered within rectangular ‘slices’ or grids.

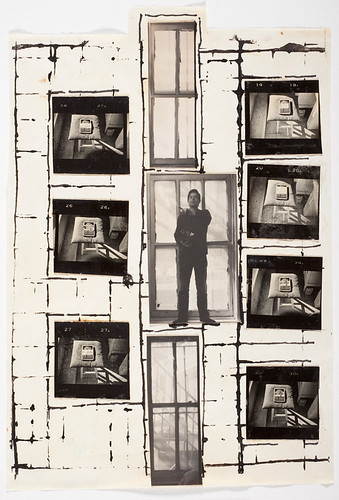

William S. Burroughs, Untitled, ca. 1972. © Estate of William S. Burroughs. Courtesy of the Henry W. And Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York

Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Burroughs’ seemingly inconsequential images shape his exploration to codify a not fully ‘out’ gay culture. He makes typologies of a subculture, creating desolate spaces within an urban landscape. One example is Untitled, 1972 showing a torn mesh fence, photographed from below so the mesh is silhouetted against a grey sky; a possibly derelict building falls out-of-focus in the background. It shares the nomenclature of the snapshot already witnessed in the Warhol images on the floor below, but two decades later.

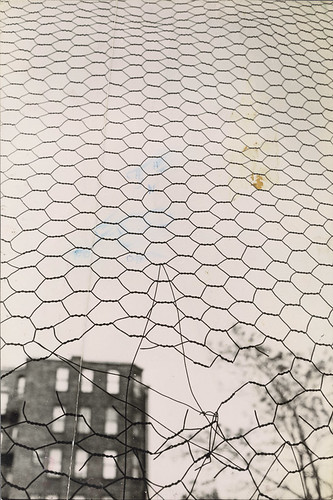

David Lynch, Untitled (Łódź), 2000. All photographs in an edition of eleven. © Collection of the artist.

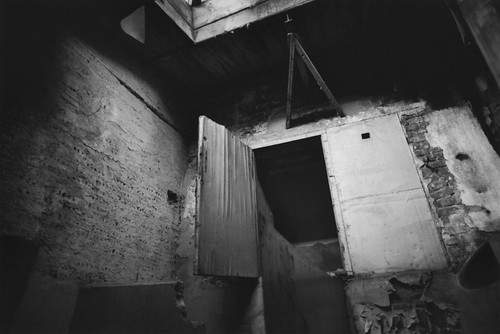

The Factory Photographs is a collection of 90 images by David Lynch, capturing twenty years of industrial decay in Europe and the US. It is the most self-conscience of the three and the images are taken for public display rather than personal curiosity.

The images capture industrial relics – engineering strength disfigured and rheumatoid. As a filmmaker Lynch is exact in his editing, providing the narrative of a building from establishing shot to close-up. The series of window images (all labelled Untitled), display the auteur at his best, creating a stark grid of the window frames that splices the sky beyond.

Lynch’s images move from haunting to maudlin; both attributes appear to be intentional.

‘Andy Warhol: Photographs 1976-1987’, ‘Taking Shots: The Photography of William S. Burroughs’ and ‘David Lynch: The Factory Photographs’ continue at The Photographers’ Gallery until 30 March 2014, with an admission fee of £4.

David Lynch, Untitled (Łódź), 2000. All photographs in an edition of eleven. © Collection of the artist.

Colin Davies, Reader in Design, Head of the School of Art and Design, University of Bedfordshire.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.