Friday, 12:30pm

29 June 2012

Graphic and grotesque

Hidden Treasure shows the human body in all its pathos and horror.

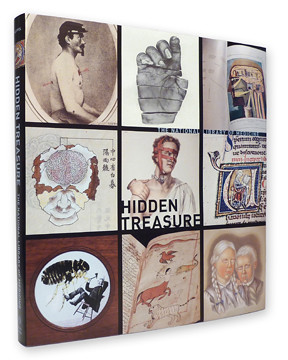

Hidden Treasure is a deceptively innocuous title for a book devoted to pictures of skin diseases, deformity, war wounds, experimental surgery and blood-chilling health warnings, writes Rick Poynor in his latest Critique. The ‘treasure’ comes from the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland, which holds more than 17 million items – books, manuscripts, prints, photographs, posters, films and ephemera – and is said to be the world’s largest archive of medical material. ‘As in any vast collection,’ notes the introduction, ‘the individual objects are buried in the sheer mass of things, even if they glow with a particular wisdom or beauty or oddness or grotesquery or wit or sadness or horror.’ Some of these items remain obscure not only to the public but even to the custodians who work there. The library has marked its 175th anniversary by bringing some of its more extraordinary artefacts into the light.

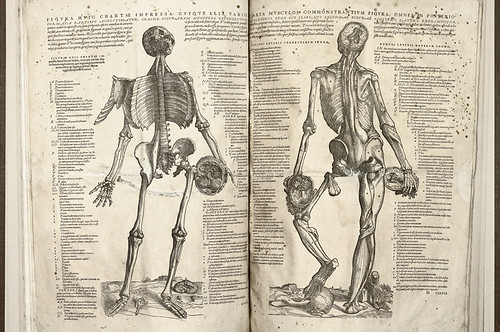

Above: The Epitome by Andreas Vesalius (Basel, 1543). Bound printed book, illustrated with woodcuts. Dissection showing the anatomy of bones, muscle, head and brain.

The book’s designer, Laura Lindgren, is also its publisher. Her Manhattan imprint, Blast Books, specialises in bizarre and unusual subjects, and she has done some elegant work for the macabre Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Hidden Treasure is structured as a series of short essays devoted to each item. The simplest have a page of text on the left, facing a main picture; other essays run to four or six pages. Lindgren allows herself small typographic flourishes – genteel italic headlines to highlight editorial themes and looping script initials in the text, both in a second colour – but refrains from competing with the visual material. Arne Svenson’s photographs are in any case often informal: pictures single out details rather than showing the entire object, less critical parts of the image drift out of focus, objects sit on top of other objects, or the background becomes part of the picture.

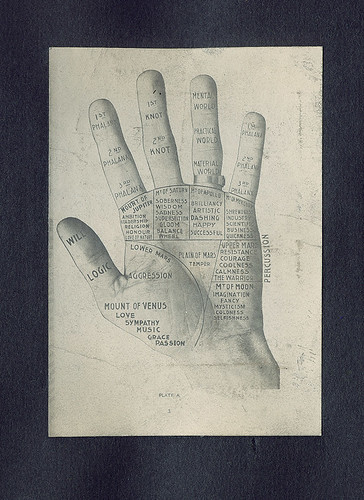

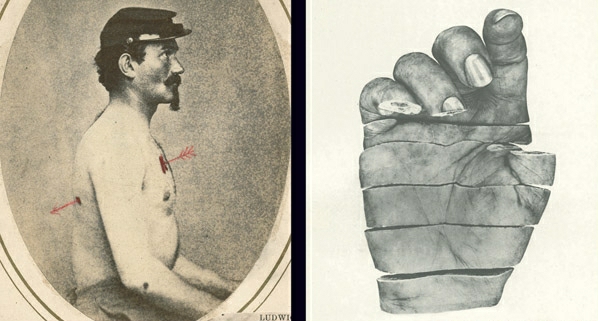

The project’s editor, Michael Sappol, a curator-historian at the library, contributes a beautifully forlorn piece about White’s Physiological Manikin (1886), an intricate feat of paper engineering with fold-open body flaps: ‘He was a gadget that does too much: a Swiss Army knife with a thousand blades.’ The life-sized paper person once dangled from a hook, but this one has lost its hook through long use and, in the photo, it slumps against the wall next to an incongruous office chair. Elsewhere, Steven Heller joins the platoon of writers marshalled by Sappol, with an essay about Huber the Tuber and Corky the Killer, cartoon characters intended to raise the alarm about tuberculosis and syphilis. Design historian R. Roger Remington celebrates Lester Beall’s brilliant covers and layouts for Upjohn’s Scope magazine, and cultural critic Mark Dery, author of I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts, sees the surrealism in antique hand silhouettes (below).

Above: Dental Hand Silhouette Gift Album by W. H. Whitslar (Cleveland, Ohio, ca. 1908). Album of gelatin silver photographs, including this palmistry diagram.

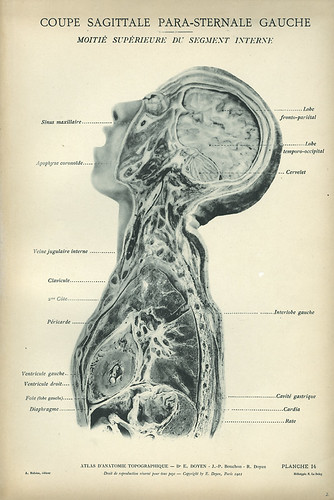

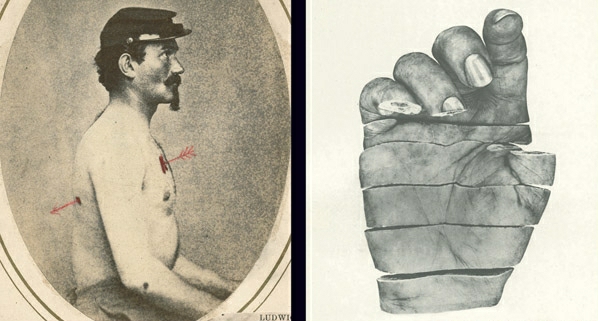

Hidden Treasure is a compendium of the greatest graphic as well as historical and human interest, though many of its images and stories require a strong stomach. At a time when engraving was the standard way of depicting anatomy and photographs were rarely used, the French surgeon Eugène-Louis Doyen subjected cadavers to a lengthy process of mummification before feeding them through a band saw to slice them into sections. For his Atlas of Topographic Anatomy (1911), the sections were photographed sequentially and then heavily retouched, giving these provocative images an eerie super-reality (below). Doyen was something of a showman and his first attempt to exhibit his human slices in a lantern-slide lecture at the Faculty of Medicine in Paris climaxed in uproar when some in the audience thought he had gone too far.

Above: Atlas of Topographic Anatomy by Eugène-Louis Doyen with J.-P. Bouchon and R. Doyen; heliotypes by E. Le Deley (Paris, 1911). Printed book in four volumes.

This revelatory album, like the immense library it represents, has much in common with the curatorial mission of the Wellcome Collection in London (see Critique, Eye no. 65 and ‘Grey matter ... in living colour’ on the Eye blog) – one of the book’s contributors is a Wellcome curator. Both institutions recognise that material collected for biomedical purposes has, with the passage of time and medicine’s great advances, become available to many other forms of interpretation. These curious objects, Sappol and his colleagues suggest, can now seem ‘more like precious evidence of something else, a resource for scholars tracing the history of medicine and health, but also the history of cities, race, factory production, sexuality, print technology, photography, feminism, motion pictures, the railroad, colonization, war, aesthetics, etc.’

The essayists, representing diverse forms of expertise, confirm this point many times over, and yet the lavish, inviting visual form of the book has its own urgency. Like one of the notorious, disreputable nineteenth-century museums of anatomy about which Sappol has written elsewhere, Hidden Treasure – its title perhaps more acerbic than it first appeared – brandishes morbid but irresistible attractions. Inside, we find an unsettling reflection of our mortal bodies in all their vulnerability, pathos and horror.

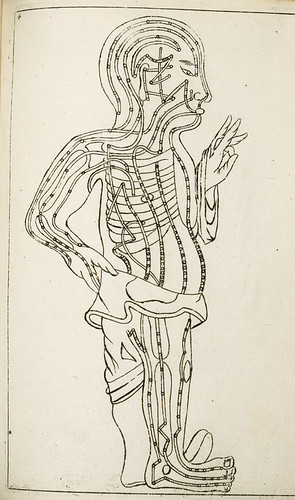

Above: Examples of Chinese Medicine edited by Andreas Cleyer (Frankfurt-am-Main, 1682). Printed book with woodcuts, engravings, charts, and plates. Double lines indicate the acupuncture meridians.

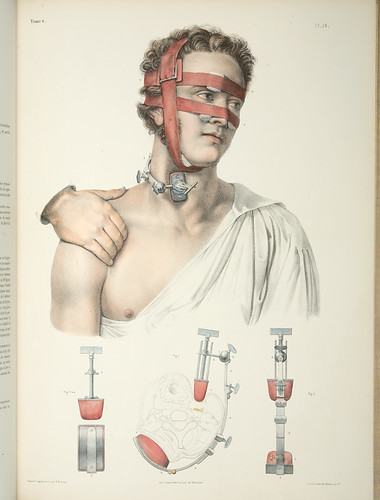

Above: Complete Study of Human Anatomy by Jean-Baptiste Marc Bourgery; illustrations by Nicolas-Henri Jacob (Paris, 1831 -54). Eight atlases with hand-coloured lithographs. Top: straps and bandages compress the patient’s facial arteries. Bottom: an instrument made to exert pressure on the carotid.

Above: Atlas of Skin Diseases by Ferdinand Hebra; drawings and lithographs by Anton Elfinger and Carl Heitzmann (Vienna, 1856-76). Printed book in two volumes with chromolithographs. Children showing a hereditary form of albinism.

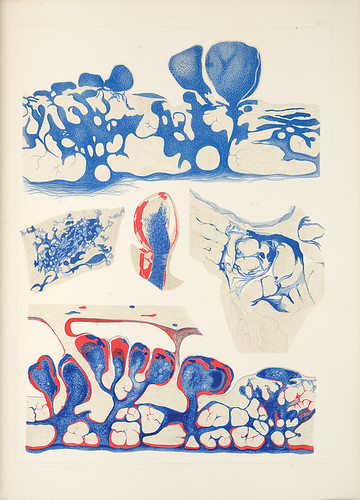

Above: Studies in the Anatomy of the Nervous System and Connective Tissue by Axel Key and Gustaf Retzius (Stockholm, 1875-76). Printed book in two volumes with colour and black-and-white lithographs. Arachnoid villi, or pacchionian bodies, of the human brain. ‘Graphic and grotesque’ by Rick Poynor was first published as a Web-only Critique on the Eye website

Hidden Treasure: The National Library of Medicine Edited by Michael Sappol. Designed by Laura Lindgren. Photography by Arne Svenson. Blast Books, $50

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. Eye 82 is out now, and you can browse a visual sampler at Eye before You Buy. Eye 83 will be on press in a few days.