Wednesday, 11:59am

30 September 2015

Pop justice

Andy Warhol

Richard Hamilton

Ushio Shinohara

Komar and Melamid

Roy Lichtenstein

Robert Indiana

Henri Cueco

Nicola L

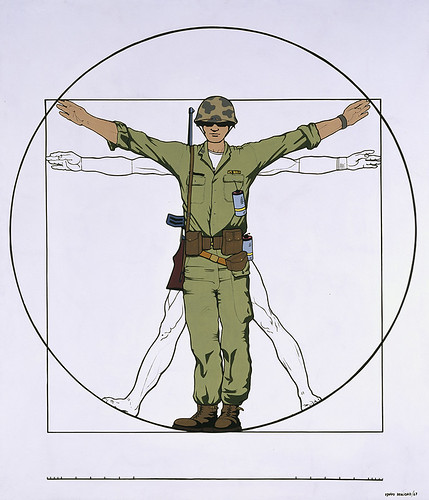

Equipo Realidad

Joe Tilson

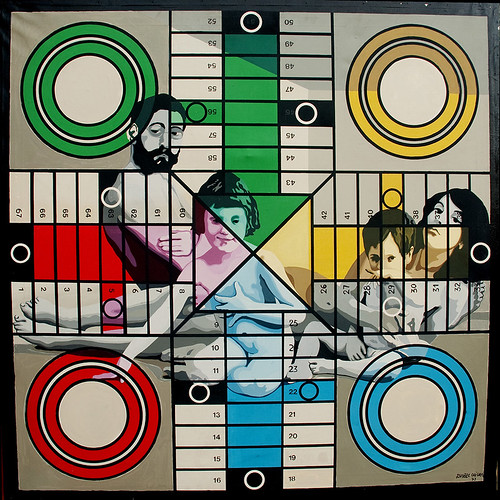

Boris Bućan

Thomas Bayrle

Toshio Matsumoto

Isabel Oliver

Jana Zelibska

art

pop

pop art

tate modern

Illustration

New media

Reviews

Visual culture

The curators of ‘The World Goes Pop’ have scoured the globe for overlooked and under-appreciated artists from a moment when art collided with the mass media

It is hard to dislike ‘The World Goes Pop’ (Tate Modern), with its mad visual assault on the senses, starting with Ushio Shinohara’s Doll Festival (1966) and finishing with Komar and Melamid’s mordant take-down of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Indiana, writes John L. Walters.

Ushio Shinohara, Doll Festival, 1966. Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art (Yamamura Collection).

Top: Komar and Melamid, Post Art No 2 (Lichtenstein), 1973. Oil paint on canvas, 107 x 107 cm. Courtesy The Boxer Collection, London.

‘The World Goes Pop’ is not a conventional blockbuster – it is huge, but made largely from the work of overlooked and under-appreciated artists rather than the stars of the Pop era – from the 1960s to the early 1970s. Many of the works are from former Eastern Bloc countries and other parts of the world marginalised, rarely patronised by the art world establishment or ignored completely.

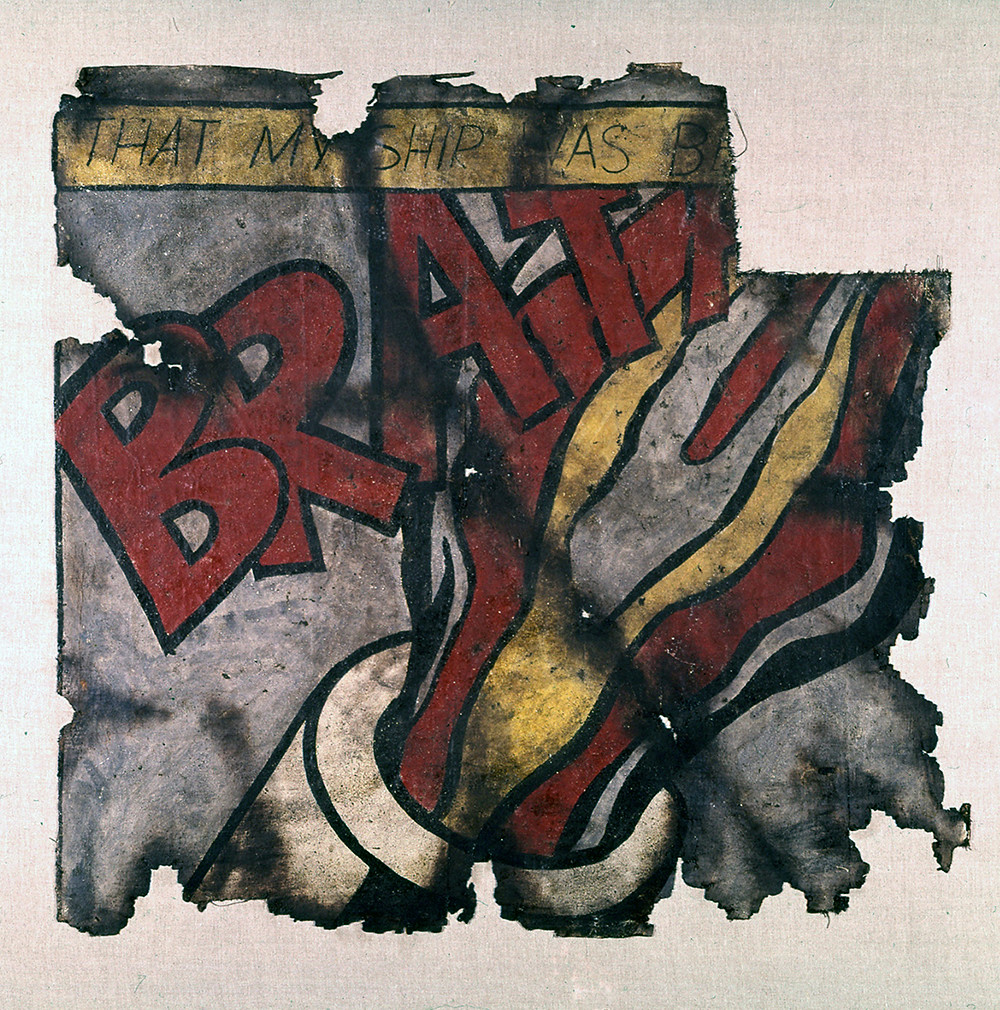

Evelyne Axell, Valentine, 1966. Oil paint on canvas, zipper and helmet 1330 x 830 mm. Collection of Philippe Axel.

Pop Art was memorably defined by Richard Hamilton in 1957 as ‘popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous and Big Business.’ Much of the work here accords with Hamilton’s list, though with rather more sex than business.

Henri Cueco, Les Hommes Rouges, 1968-9. © Henri Cueco/ADAGP 2014. Photo: David Cueco.

‘The World Goes Pop’ depends for its impact not on big names, but on bold curation and a provocative interpretation of the recent past. The curation team – Jessica Morgan and Flavia Frigeri with Elsa Coustou – has scoured the globe for work that delineates a broader version of Pop Art. They have returned with a big bright bag of treasures and previously unknown pleasures. This is not a show whose artists are meant to replace or even augment the canon – it is a challenge to the very idea of a Pop Art canon, when the comic book art and advertising appropriated by Pop is now better documented and understood as part of culture in general.*

Nicola L, Red Coat, 1973. Collection of the artist © Nicola L.

Art history often paints the brief rise and fall of Pop Art alongside the emergence of conceptual art, but Morgan argues that Pop could easily be regarded as a form of the latter. Nicola L’s Red Coat (1973), a raincoat that can be worn by eleven highly co-operative people, supports this argument, as does the appropriation of editorial and brand design by artists Joe Tilson and Boris Bućan.

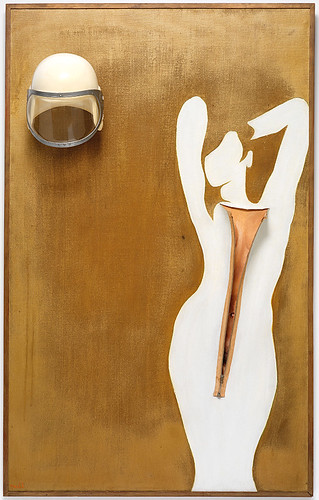

Joe Tilson, Page 19 He, She & It, 1969–70. Screen and oil on canvas on wood relief, 187 x 126 mm. Museum Het Valkhof, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. © DACS 2015.

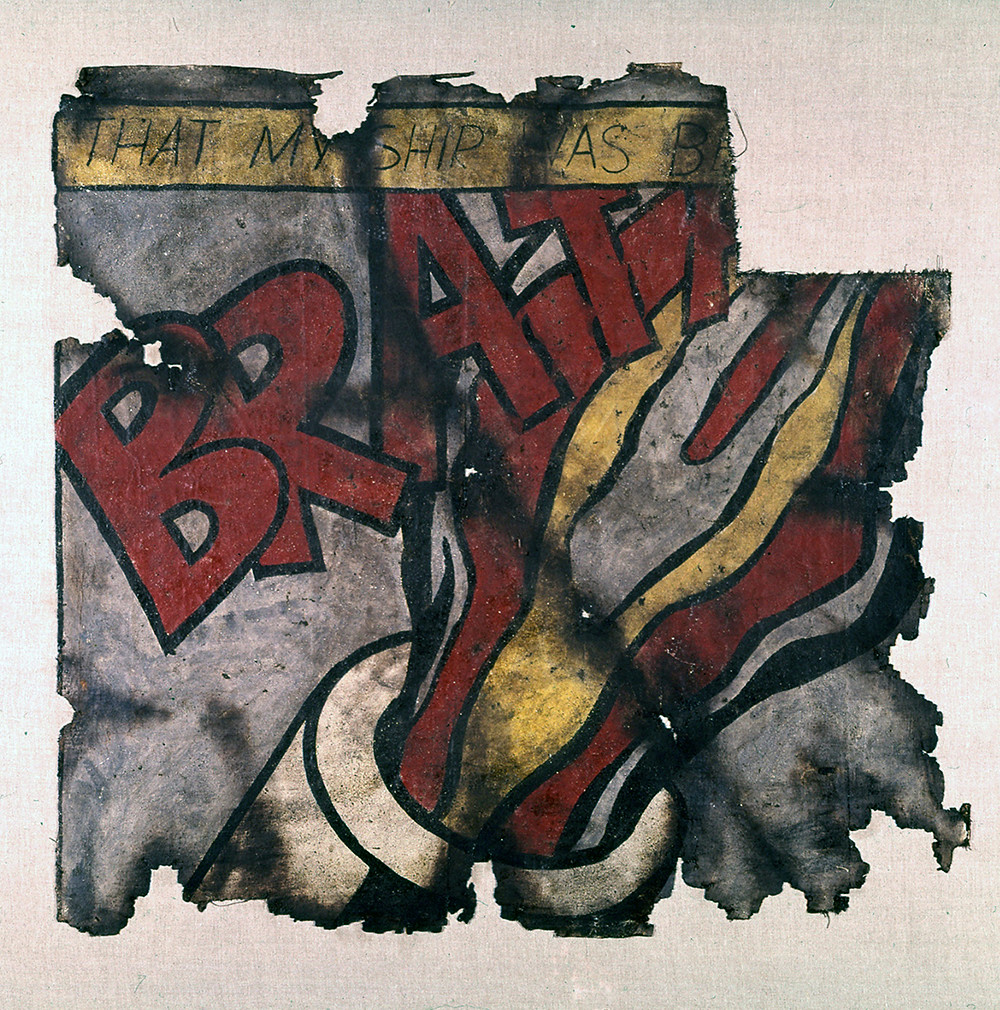

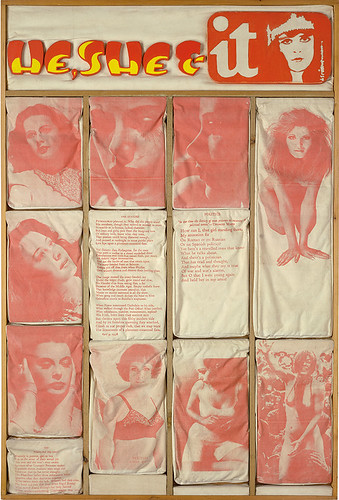

Boris Bućan, Bućan Art, 1973. Acrylic on canvas, 499 x 699 mm. Marinko Sudac Collection. © Courtesy of the artist.

Boris Bućan, Bućan Art, 1972 (detail).

Background: Thomas Bayrle, The Laughing Cow (Blue) Wallpaper [La Vache qui rit (blau) Tapete], 1967/2015.

Tilson copies huge page layouts, while Bućan repurposes a series of easily recognisable logos, replacing the brand name – Coca-Cola, IBM, Marlboro, Pan Am, etc. – with the word ‘Art’.

In many works in ‘The World Goes Pop’, whatever visual delight is on offer (and the Red Coat must have been an amusing sight as Tate employees trundled over the Millennium bridge) remains subservient to the idea.

Judy Chicago, Birth Hood 1965-2011. Sprayed automotive lacquer on car hood. Courtesy Judy Chicago/Riflemaker London. Photo: Donald Woodman. © Judy Chicago/DACS 2015.

There is a political edge to the show. Where Anglo-American Pop Art might celebrate mass consumption, many of the works here deliver a bitter critique. And a broader political note is sounded by the proportion of work (around two-fifths) by women artists – not quite 50:50 but an interesting change from the more usual narratives of art history.*

The final room, titled ‘Pop Consumption’ contains several polemical works, including Komar and Melamid’s ‘Post Art’ (1973) works, which imagine fragments of famous Pop Art artefacts salvaged from a global catastrophe, and Bućan’s straight-faced ‘art’ logos, Thomas Bayrle’s The Laughing Cow wallpaper (1967) and Toshio Matsumoto’s short film Mona Lisa (1973).

Not everything is as conceptually coherent as these small focused pieces near the end. There are places where the sheer size of Tate Modern threatens to swamp the work on show (for example Isabel Oliver’s series ‘The Woman’).

And some works appear to have been chosen for their ability to fill a room – Jana Zelibska’s sexy theme-park-like Kandarya – Mahadeva, could probably be shoe-horned into several group shows with totally different themes. Its strategically placed mirrors are popular with visitors taking smartphone selfies.

Jana Zelibska, Kandarya – Mahadeva, 1969. Environment, mixed media, plastic, mirrors, paper, neon lights. Linea Collection, Bratislava. © Jana Zelibska.

However the sheer quantity of work is also a quality of ‘The World Goes Pop’. The show is like one of those superior World Music compilations (from labels such as Analog Africa and World Circuit), packed full of artists you have never heard before, yet whose very existence throws open a whole new way of understanding a genre, a place or a historical moment. For ‘The World Goes Pop’, the research, the graft, the excavation of unknown, unheralded art and visual culture from the 1960s and 70s is part of the story, and it is a story worth telling.

‘The World Goes Pop’ continues at Tate Modern, Bankside, London until 24 January 2016.

* Lichtenstein’s appropriation of comic books is discussed by Rian Hughes in the Eye 39 article ‘Meanwhile in the weird world of art’.

Equipo Realidad, Divine Proportion, 1967. Acrylic paint on board 131.5 x 114 cm. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid Photographic Archives Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. © DACS 2015.

Isabel Oliver, La Familia (from the series La Mujer), 1971. Acrylic on canvas, 980 x 980 mm. Collection of the artist.

Boris Bućan, Bućan Art, 1972 (detail). Background: Thomas Bayrle, The Laughing Cow (Blue) Wallpaper [La Vache qui rit (blau) Tapete], 1967/2015.

![Boris Bućan, Bućan Art, 1972 (detail). #worldgoespop Background: Thomas Bayrle, The Laughing Cow (Blue) Wallpaper [La Vache qui rit (blau) Tapete], 1967/2015.](https://farm1.staticflickr.com/673/21387762716_4664b13525.jpg)

John L. Walters, Eye editor, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.