Summer 1991

Guerrilla graphics

Design has the power to effect change. Now it must develop a social conscience

It may seem a trivial question in the wake of America’s ‘victory’ in the Gulf, but this is a propitious time to ask: ‘what has graphic design done to change the world?’ Desert Storm provided a textbook example of how a nation, indeed the world, could be caught up in a tornado-like propaganda effort that successfully swept aside virtually any attempt at dissent. US Government control was so effective that otherwise rational people were sucked into the patriotic vortex. Few dissenters were heard in the media, least of all graphic designers as a group, and I know of only two who could muster the presence of mind and personal resources to print anti-war posters which they then distributed themselves. While this does not imply that graphic designers could have altered war policy, it does mean that few even tried.

Designer response was disappointing, but not at all surprising. For the last decade, as a profession, graphic designers have been either shamefully remiss or inexcusably ineffective about plying their craft for social or political betterment. While traditionally, graphic designers in America have tended to lean toward the liberal side of the political seesaw, in recent years one would be hard pressed to find visual confirmation of this in either the design annuals or on the street. Evidence of designer concern is found in the form of well-meaning but woefully masturbatory poster exhibitions and portfolios organised on general humanistic themes such as peace, human rights and the environment. Getting several hundred international practitioners to design and produce their own posters may be a show of solidarity, and might occasionally produce something of symbolic value, but many of the designers invited are far more interested in throwing together another good portfolio piece.

Thematic shows which posit social relevance as a design problem are doomed to failure. When designers and illustrators have nothing to say about a subject they say it obtrusively. Themes like war and peace, the environment and the economy are simply too enormous for anyone to make sense of, let alone try to solve in one graphic image. Once we’ve acknowledged that designers have certain inherent limitations as message bearers, the question that must be asked is: ‘Can graphic designers actually do something to change the world?’ The answer is ‘yes’, if one disregards the fact that there are very limited outlets for this kind of work, and accepts the fact that being socially responsible means taking the initiative oneself, dealing rationally with issues, and having a commitment to a specific cause.

The designer’s power comes directly from the design medium itself and will have positive effects only if that medium is used efficiently. Sue Coe provides a good example of what one might call ‘surgical propaganda’: The art of effectively targeting a problem area. Though trained in England and best known in the United States as an editorial illustrator, her unique talents have been remarkably under-utilized by most editors and art directors, who are afraid of her strong, polemical voice. Indeed, it is the work of imitators, who reproduce Coe’s style, without her content, which is more frequently published. Coe is therefore forced to find alternative outlets for political expression. In small press journals and books, print and painting exhibitions, she has focused on one critical area: animal abuse. Her lurid images of slaughterhouses, rendered in pencil, gouache and oil, expose commercial killing centres to be as hideous as any human death camp. However, the purpose of Coe’s work is not just to provoke public outrage, but to influence new legislation, and she will be satisfied if she can in any way help to alleviate the inhumane treatment of domesticated animals. In fact new animal protection statutes to US Government food production restrictions are now pending, in part owing to Sue Coe’s efforts.

Although lately the hermetically sealed fine-art world has become more hospitable to social and political activity, mainstream graphic designers have not, in fact, created anything like a critical mass of socially relevant propaganda. Nevertheless, in recent years there has been interesting guerrilla activity in the form of strategically lobbed graphic barrages from anonymous individuals and design collectives such as Gran Fury, the graphic arm of the AIDS activist group Act Up. These guerrillas have produced an arsenal of inexpensive printed pieces which, more often than not, are illegally hung or pasted on lamposts, mailboxes, hoardings and walls. The design is functionally transparent, printed on small presses or photocopiers, on cheap paper, and is usually left unsigned. The difference between many of the purposeful, professionally designed pieces and their amateurishly produced counterparts comes down to effectiveness. A professionally designed flier will usually have more authority, if not visual appeal, than a more casually produced one.

In addition to bringing a certain design clarity to social and political messages, the guerrillas have also had an effect on mainstream design. An increasing number of American designers are now taking a more active role in their communities by doing pro bono work. But pro bono must not be viewed as merely as conscience-soothing ‘charity work’, but rather as a commitment. The occasional good deed is unlikely to change very much at all. What designers must do is take the initiative, select their own causes to champion, and be prepared to devote themselves to carrying out work in the cause’s best interest, not their own, over a long period of time. Graphic designers might not have the power to earn millions for a cause or regularly change legislation, but they can make some changes in the world if only an effort is made.

Steven Heller, design writer, New York

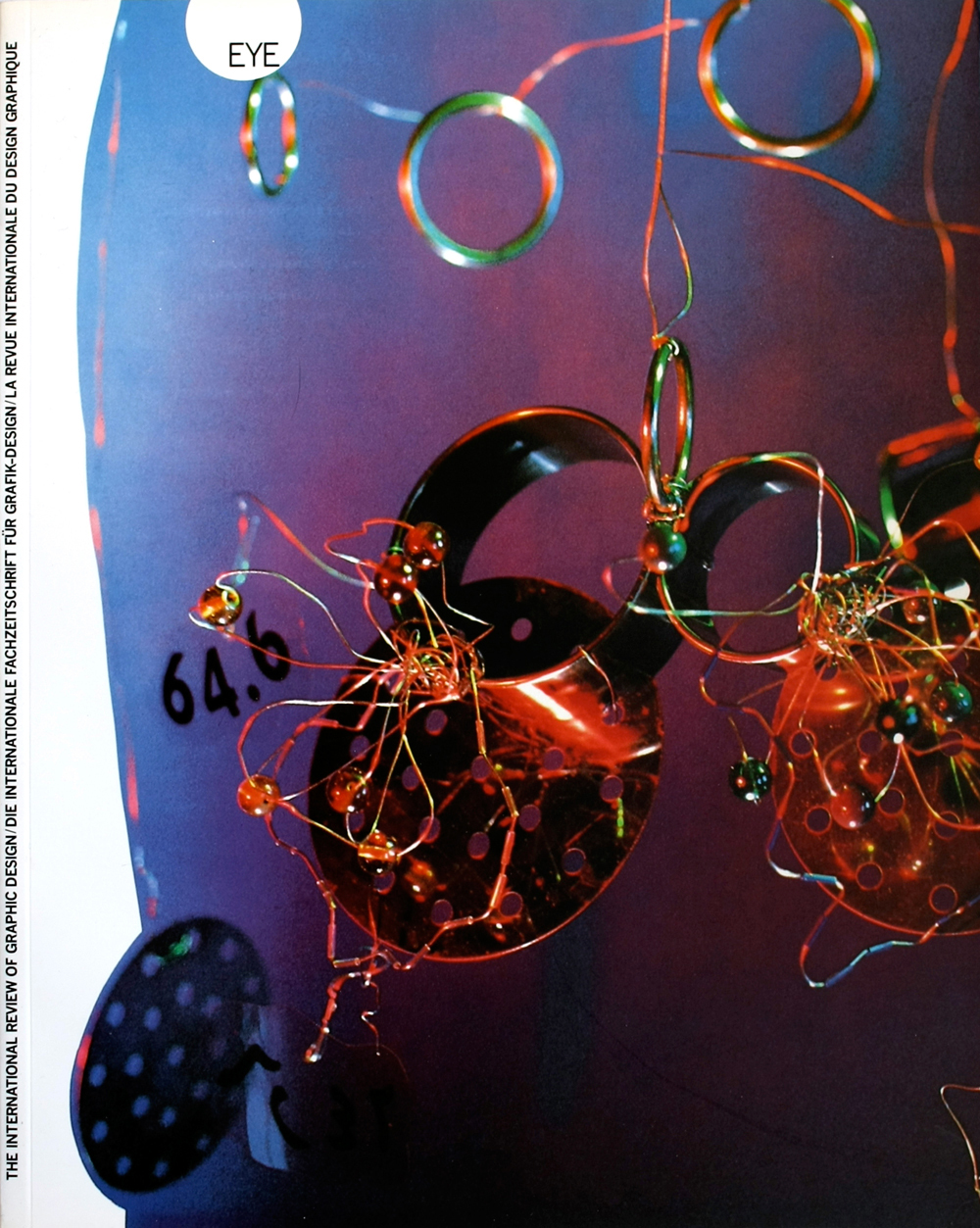

First published in Eye no. 4 vol. 1 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.