Spring 2002

A design show that's not about design

Web Wizards: Designers who define the web

Design Museum, London<br>30 November 2001–21 April 2002<br>Although Web design has been established for well over half a decade, the job of displaying, archiving and documenting design work has been slow to get off the ground. While the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis has the most extensive programme addressing digital art, the Design Museum’s ‘Web Wizards’ (sponsored by Christian Dior Couture) is the first large-scale exhibition to address what it refers to as ‘one of the most dynamic areas of contemporary design’. Well designed by Studio Myerscough, with Ben Kelly consulting, it is a stimulating and enjoyable show. Disappointingly, however, it is not about design.

The show features five ‘wizards’: Joshua Davis, the David Carson of Web design, who works with the New York-based Kioken studio; Yugo Nakamura, a civil engineer and landscape architect working in Tokyo, who brings a ‘craftsman’s approach’ to Web design; Daniel Brown, a creative technologist who until recently worked at Amaze in the UK; Canada- and US-based collaborators James Paterson and Amit Pitaru, whose work combines image, music and movement; and London-based Tomato Interactive, the most commercially focused of the group. The other element of the show is a history of the digital image with about 50 landmark examples of game console and computer design, from early Ataris and Commodores to the Apple Newton MessagePad and Macintosh Plus, along with installations of vintage computer games and an elegant timeline of the digital age.

One of the curatorial issues posed by work that is wholly digital is why people need to come to a museum to experience it. One reason is that audiences may not have access to a computer with the high-bandwidth connection for which these exhibits are intended. Some work is intended to be shown on a scale or with sound presentation that is unavailable to most people, as is the case with Paterson and Pitaru’s pieces. A museum can also present supporting material with a work, for instance the implementations of Tomato Interactive’s Connected Identity for Sony as stings at the end of television adverts for its products. Not least, a museum environment is also more conducive to reflection, and to interaction and discussion with others.

Nevertheless, having ‘Web’ in the exhibition title implies that the work may have some relationship to the concept of networks, yet all of the pieces could be (and are) experienced offline. The show is really about creativity expressed through the technologies that the Web has promoted and made accessible: HTML and Flash, but mainly Flash.

Technologies are not prominently referenced in other Design Museum exhibits: the continued celebration of Flash in ‘Web Wizards’ might lead one to conclude that Macromedia is a silent sponsor. Yet much of the work in the show could have been produced using analogue techniques. This is most noticeable with Paterson and Pitaru’s work, wonderful as it is, and is also true of Davis’s pieces (though they are not typical of his work).

The vintage games exhibit, while fascinating, does not explore the aesthetics or design of either the hardware or software. Web designers will need to learn a lot from games designers in the coming years, and they would do well to learn about product design, too, as the computer-based Web browser is no longer the main place where we interact with interfaces.

Despite the subtitle ‘Designers who Define the Web’, most of the work on show is art. If you believe that design involves a client with an objective distilled into a brief to which the designer responds, then the presentation of design solutions should illustrate the design process, show work-in-progress, allow the designers to explain how their solution answered the brief, and indicate whether the design solution was successful. Tomato Interactive’s Connected Identity for Sony is the only design project in the show, and while it is well presented, the focus is still on the outcome rather than the process.

In an online chat hosted by Guardian Live Online to accompany the opening of ‘Web Wizards’ Josh Davis said: ‘If I had to label myself I’d consider myself more of a traditional artist. ‘That said,’ he continued, ‘I think the show at the Design Museum was looking to collect people who were helping affect design, whether we choose to call ourselves designers or not.’ So let us address the show on these terms.

It is certainly the case that digital artists can play an important role in helping designers, technologists and clients get a feel for the new medium. Davis claimed that ‘the very act of building and publishing experimental work educates a client in what is possible and not’.

Aspects of the digital network that are new – and that we might better understand through exploration by artists – relate to physical space and geography, to time, to the context and profile of the user, and to their interaction with others through the network. The digital network does not exist in isolation from the physical world, and many interesting artistic explorations have taken place at the interface between them. There are also valuable artistic investigations within the digital realm. While ‘Web Wizards’ champions the creators of the most ‘aesthetically innovative websites of recent years’, the work presented does not begin to get to grips with the real aesthetics of the digital.

The curators could have learnt from MIT Media Lab superstar John Maeda, who said: ‘we are in an age when the painter doesn’t really know about paint’, or from Visual Language Workshop co-founder Muriel Cooper who noted that, ‘when you start talking about design in relation to computers, you’re not just talking about how information appears on the screen, you’re talking about how it’s designed into the architecture of the machine and of the language.’

Nico Macdonald, Educator, London

First published in Eye no. 43 vol. 11, 2002.

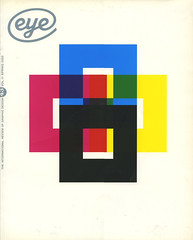

Eye is the world's most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.