Summer 2012

Dan Dare, Bunty and all their pals

British Comics: A Cultural History

By James Chapman, Reaktion Books, £25

James Chapman states his intentions openly: to trace the development of the British comics industry (from the late nineteenth century to the present day) with reference to the culture that surrounded and arguably inspired some of the UK’s most famous comics. At this he certainly succeeds.

All the favourites are here: from Ally Sloper to Eagle to anthology cartoon comics (Beano, Dandy); girls’ magazines (Girl, Bunty, Misty), boys’ adventure and war stories (Battle, Action), science fiction (2000AD) and superheroics (Marvelman / Miracleman, Zenith); to the adult and alternative (Escape, Viz, Warrior).

Chapman’s analysis of key characters such as Dan Dare in their various incarnations (from space chaplain to ‘Pilot of the Future’ to a Dark Knight-style reboot as an ageing cripple in Revolver) is absorbing.

Even when discussing well known characters, this book is full of interesting titbits: Winston Churchill’s animosity towards DC Thomson (due to a press campaign against him in the 1920s) is one such example from the chapter ‘On the Wings of Eagles’, and gives colour to the emergence of UK legislation such as the Children and Young Person’s (Harmful Publications) Act 1955.

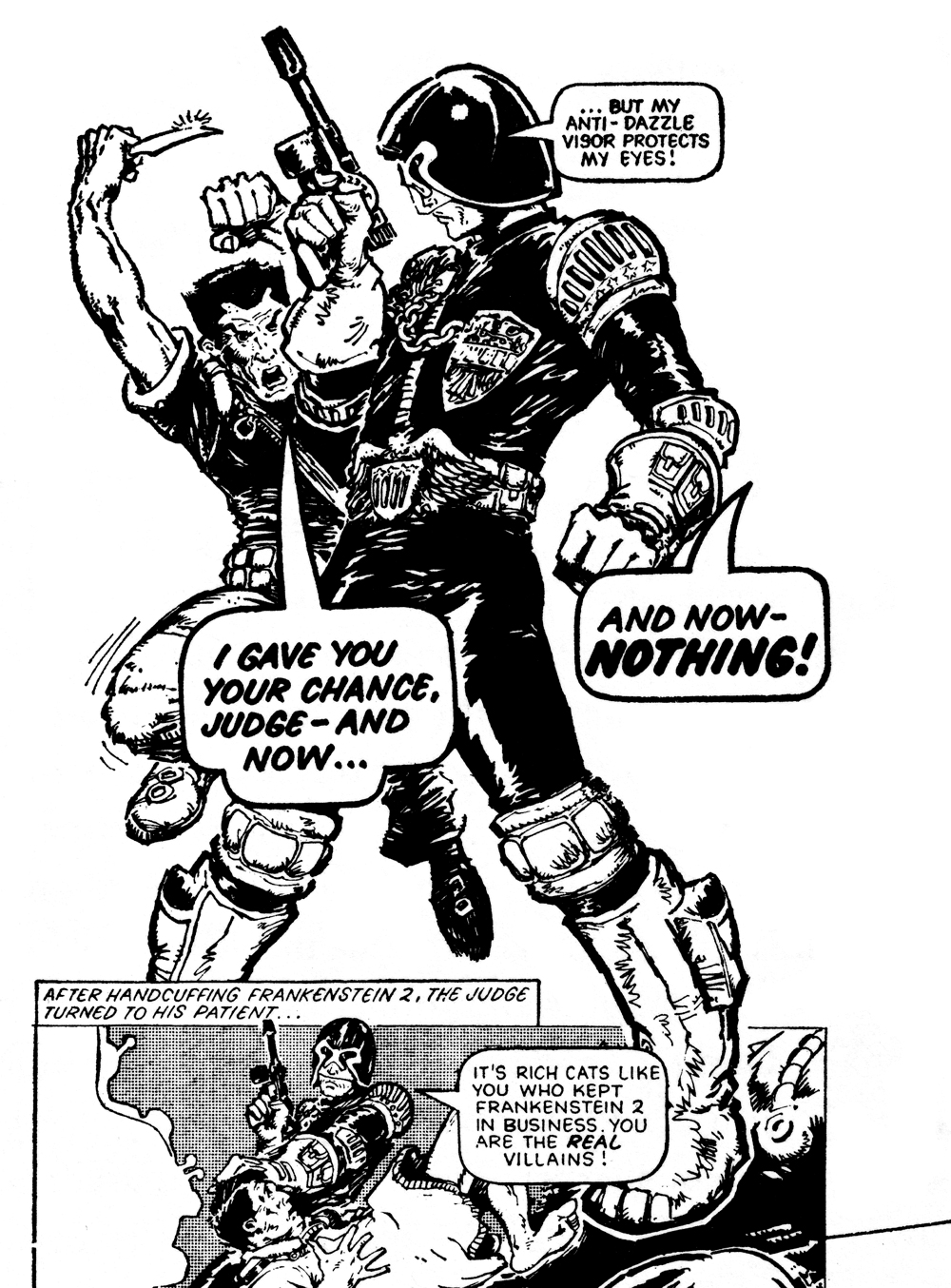

Cover of British Comics uses an illustration by MaryLB. Top: detail of a Judge Dredd page from 2000AD, 2 April, 1977.

From an academic perspective, Chapman’s attempt to situate both creators and product in relation to social history is fascinating. Parallels with cult film, TV and literature (Chapman is a professor of film studies) inform many of his analyses, alongside audience response. However, this theory is mostly implied, and British Comics is a readable and detailed discussion.

The quotes used to begin each chapter are well chosen and from a wide range of sources (ranging from cover blurbs to fan letters to scholarship to creator commentary). The inclusion of primary material makes it a useful scholarship aid, with some limitations. In providing a historical overview Chapman does neglect the present somewhat (Web comics are not discussed at all) and the cultural history of the UK is outlined in broad strokes only. That said, his observations and conclusions are spot-on and there is an incisive accuracy to his summaries.

In its summary of the ideological and social conditions of comics publishing at certain periods, this book put me most in mind of Martin Barker’s A Haunt of Fears (1992), which surveys the 1950s British campaign against horror comics, and Amy Kiste Nyberg’s Seal of Approval (1998), a history of the American comics code, albeit with a much wider historical scope than either. There are also significant echoes of Roger Sabin’s Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels (1996 / 2001) – a larger and much more lavishly illustrated book with a global scope.

Chapman’s book doesn’t move far beyond the areas covered by Barker and Sabin, and his discussion of the contemporary is all too brief, but his ‘Brits-only’ focus does produce a comprehensive historical survey with some depth. Like these other publications, this not just an academic book – its lively and interesting style makes it more than suited to the active fan and those nostalgic for the comics of their youth.

First published in Eye no. 83 vol. 21 2012

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.