Spring 2016

Fighting back with pictures

Visual Impact: Creative Dissent in the 21st Century

By Liz McQuiston<br> Designed by TwoPoints.Net / Studio Chehade<br> Phaidon, £24.95<br>

This is the third book which Liz McQuiston has written on graphic protest in the past twenty years or so (four if you count her historical survey of feminist imagery Suffragettes to She-Devils). The first, Graphic Agitation: Social and Political Graphics since the Sixties, was published in 1993 and the second, Graphic Agitation 2: Social and Political Graphics in the Digital Age, came out a decade later. Just over ten years on, Visual Impact: Creative Dissent in the 21st Century is a new volume in what is effectively a trilogy. McQuiston has approached her new book – like the other two – much like a curator. She reproduces a tremendous amount of material from around the world since 9/11. All of it is carefully and accurately contextualised (no mean achievement when writing about inflammatory subjects such as Israel /Palestine). But, when it comes to judging the images, much is left up to the reader.

The implicit promise of her catalogue is ‘this material will repay your attention’. And it does. Visual Impact features Stelios Faitakis’s tempera and gold-leaf paintings representing the chaos caused by debt crisis in Greece in the manner of Byzantine icons; the irreverent anticlericalism of Pussy Riot; anti-corruption and anti-gentrification poster campaigns from the backstreets of Rio in the run-up to the 2012 World Cup; the militant response of French society to the murderous attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo in January 2015; and many other darkly bitter but often humorous responses to crisis and injustice.

The fact that McQuiston has compiled three volumes – each a decade or so apart – allows the curious reader to reflect on the deeper shifts in creative dissent over the past half century. What stands out in her latest volume is the relative decline of what used to be called identity politics (focused on matters of multiculturalism, sexuality and gender equality) and the rise of images responding to the upsurge of violence in the world since 9/11. Of course, the two are still lashed together – for instance, in incendiary debates about ‘the veil’. Unsurprisingly this issue directs McQuiston to France where, in the run up to the 2011 ban on ‘the concealment of the face’ (‘la dissimulation du visage’), artist Princess Hijab painted thick black paint on the faces of semi-naked figures in ads promoting underwear on the Paris Metro. These dripping veils did not last long before the Metro staff wiped the glazed frames ‘clean’.

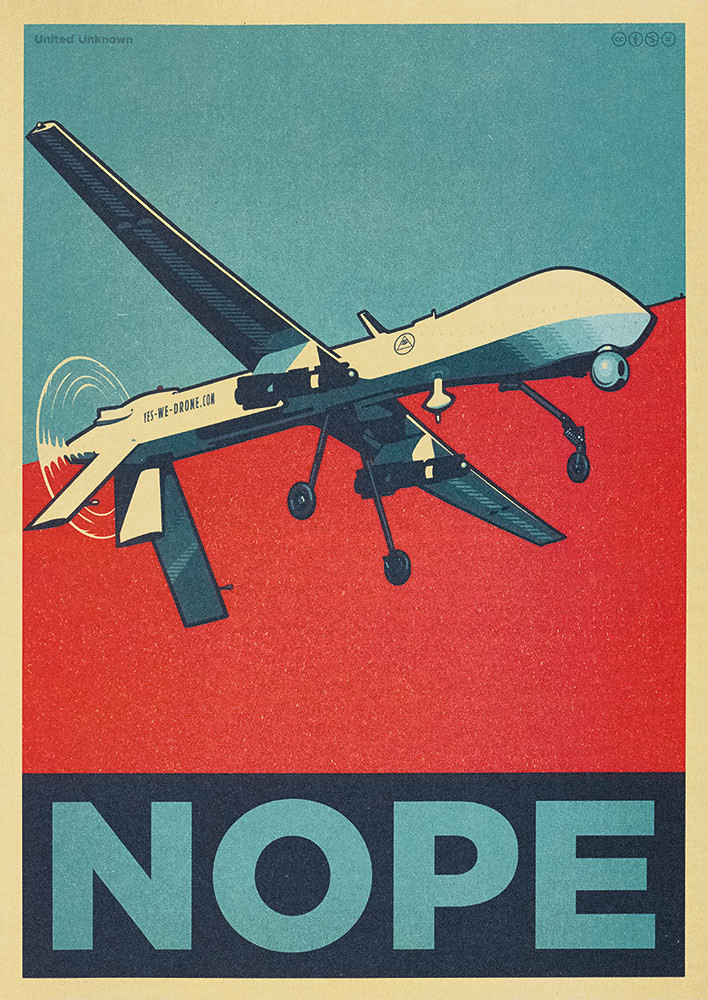

Perhaps another diagnosis which might be made of McQuiston’s long-term project is the relative decline of irony. It is still present, not least in response to the Anglo-American prosecution of the ‘War on Terror’, as illustrated by Dorothy’s ‘The Guantanamo Bay Collection’ (2009-10), a fashion shoot for Ctrl.Alt.Shift magazine, in which hooded models in bright orange uniforms are waterboarded. But the border between political satire and ethical ambivalence had already been eroded by fashion photographers and advertisers well before designer-artists such as Dorothy set to work. Recall Steven Meisel’s ‘State of Emergency’ fashion shoot for Vogue Italia in 2006 which translated images of torture at Abu Ghraib into consumer goods (see Critique in Eye 62). What speaks loudest in McQuiston’s book is often a direct and concise form of protest, such as that of Erdem Gündüz in Istanbul’s Taksim Square in 2013, whose act of defiance was to stand still and silent. Hundreds joined him.

The question which hangs over many of the images in this book, and is raised by its title, is that of impact. For too long ‘progressive’ artists and designers have mistaken good intentions for effectiveness. Subvertising, hacktivism and other ideological mash-ups have provided comforting illusions of engagement while changing little. If protest images are to be judged, it ought to be by what they do. This is true, even when they ‘fail’. Some of the most powerful examples in McQuiston’s compendium are those which reveal the inclination of power, even in democratic societies, towards control. Artist Steve McQueen’s ‘Queen and Country’ project sought to put portraits of British troops killed in Iraq on British postal stamps. This tender monument was backed by the majority of the families of the dead, but his proposal failed to attract the support of the Director of the Royal Mail.

McQuiston is interested in understanding the setting where these images appeared. During the Occupy Movement and the Arab Spring protests, this often meant the street. Stencilled images sprayed onto walls in Cairo in 2012 to highlight the violence on which Mubarak’s regime relied and improvised newspapers like The Occupied Times testify to the urgency of the moment. Appearing under the noses of Egypt’s Central Security Forces or CCTV cameras in the City of London, these designs set out to delineate what anarchist theorists like to call a ‘temporary autonomous zone’ in which alternative ways of living might be imagined or tested. But running throughout McQuiston’s book are new forms of graphic activism which were produced at some distance from the events which they sought to influence. ‘Electronic posters’ – designs that can be downloaded and printed – were created by the anonymous collective Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh [The Syrian People Know their Way] in 2012. The internet provided not only the means for expressing dissent against Assad’s Ba’ath regime in Syria but also anonymity in the face of considerable risk.

A comparison might be drawn here with mydavidcameron.com, a website created during the 2010 General Election that gave users an online generator to rewrite the slogans of Tory publicity or replace an airbrushed portrait of the leader with less flattering images. In one design by Loudribs, the former Etonian appears in a hoodie announcing: ‘Yo Plebs, we is all in dis ting together, yeah?’ Undoubtedly funny, and perhaps accurate too, but Loudribs’ design seems strikingly close to internet trolling. Dissimulation and ironic distance – the characteristic features of so much online expression – may yet act as a brake on the kind of commitment upon which so much creative dissent relies.

Cover design by TwoPoints.Net / Studio Chehade.

Top: ‘Electronic poster’ by United Unknown, 2013.

David Crowley head of Critical Writing in Art & Design programme at the Royal College of Art, London

First published in Eye no. 91 vol. 23, 2016

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.You can see what Eye 91 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.