Winter 2007

Whose space?

When the demands of Neoliberalism play havoc with our lives, it is time to fight back, and designers wield the sharpest tools

We live in a world dominated by Neoliberalism, which establishment politics accepts as the only way to run society. This economic doctrine claims that we are best served by maximum market freedom and minimum state intervention.

The conditions that Neoliberalism demands – minimal taxes, the dismantling or privatisation of public services and social security, deregulation, the breaking of the unions – just happen to be the conditions required to make the elite even richer (with a shift of wealth to the top tenth of one per cent), while leaving everyone else to sink or swim.

But what does this have to do with graphic design? Well it helps to explain the current dominance of corporate culture in the forms of advertising and branding, to the point where graphic communication is merely a ‘service industry’ for those interests.

Photo Op by Kennard Phillipps (Peter Kennard and Cat Picton Phillips), 2005.

Outlined in these pages are practical examples of graphic resistance across a range of media drawn from artists, designers and studios who have worked within and around the anti-capitalist and anti-war movements of the past decade or so and have given voice to the ‘social crises’. Some projects are in the tradition of agit-prop; others are from the related field of culture-jamming. Each holds a seed of inspiration and hope for those pondering what is to be done.

Neoliberalism’s ideology of individualism is reflected in culture with the increasing obsession with the self and appearances. In the academic world, similar views are expressed through varieties of Postmodernism, whose claims for the fragmentation of reality, or the ‘relativity of truth’, echo the rhetoric of the Neoliberal cause.

Becoming more decollectivised, more atomised and isolated as individuals, as these policies spread through society, has a psychological cost: depression is now the second biggest threat to health in the West.

And yet all this masks the fact that never has there been such inter-connectedness when it comes to everyday life: each of us relies so heavily on the labour of others globally. Yet the institutions and social relations of Capitalism that organise such a high level of social co-operation also produce the alienation – by not allowing us control over what we produce – that separates us from each other. The system is now more destructive than progressive, and threatens life as we know it through climate change and war. In the cultural field, outdated intellectual property conventions constrain the potential of a free, globally shared culture, accessible to all.

This is not to lay the blame on the shoulders of the beleaguered graphic designer who is attempting to make a living. Attempting to commodify creativity or ‘innovation’ has been important for Neoliberal economies and this has put increasing commercial pressure on all areas of culture – the ideas factory becomes then not so different from the traditional factory. Where the difference in designers’ labour does lie is in the intimate connection between value for Capital and our own minds and bodies. Creative labour practised by cultural workers constitutes a problem for Capital’s command and control over it. This contradiction expresses itself in graphic design in debates over what is ‘good’ design and the thorny topics of morality and ethics.

In Marxism and the Philosophy of Language (1929), Valentin Volosinov, a Russian revolutionary who was part of the Bakhtin school, developed ideas of signs, language and communication that placed the emphasis on the human utterance as a creative part of an ongoing dialogue between speaker and listener, in specific situations in which a creative role was assigned to each. In this is also outlined a dialectics of morality for sign production. His theories provide a better framework for understanding signs than the dominant theories from Saussure onwards, which have treated communication either as an abstract, structuralist inspired system of ‘signifiers’ and ‘signified’ somehow outside of human beings’ use of them and bracketed off from the material world or the free-floating postmodernism of the 1980s and 90s.

Volosinov saw a sign as an intersection of differently oriented social interests – the site of class struggle. Different social groups or classes use the same sign or the same social language but with different ‘accents’. It is thanks to the ‘social multi-accentuality’ of the sign that it can retain its vitality and dynamism, offering the capacity for further development. ‘Any current curse word can become a word of praise, any current truth must inevitably sound to many people as the greatest lie. This inner dialectic quality of the sign comes out fully in the open only in times of social crises or revolutionary changes,’ he writes.

Design is not just an ‘industry’: it goes to the heart of what it means to be human. The ability to use our creativity to transcend our limits as individuals and as a society is surely needed now more than ever. Radical social change will be necessary to see off the triple threat of the ‘war on terror’, Neoliberal economic policy and climate change, but to be radical means to get to the root of the problem: Capitalism itself.

One of the most organised expressions of designers’ collective desire to do the right thing is the First Things First manifesto (see Reputations, pp.60-69), which pointed to a different set of priorities for graphic designers. The revived First Things First 2000 (see Eye no. 33 vol. 9, 1999) created a stir, but that was eight long years ago. The time for pledges has gone and it is time for action. Graphic communication cannot be limited to the process of selling commodities, it is a powerful tool for both re-imagining the world, and expressing the truth of our situation. Those of us who love design must use it toward these ends or we may not have a future to imagine, let alone a present to enjoy. Neoliberalism has created a powder keg of possibilities – maybe now is the time to light the graphic fuse.

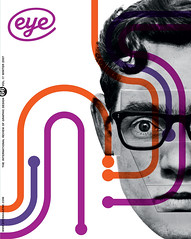

First published in Eye no. 66 vol. 17, 2007

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.