Winter 2010

Bullet point

Christopher Wilson is struck by flaws in the graphic analysis of JFK’s death

Information design is dependent on quantifiable data. A map relies on known details of land mass and boundaries; a timetable on when the train is intended to arrive and depart. The field therefore usually avoids situations where the data is uncertain. The diagrams illustrating the so-called ‘magic bullet’ or ‘single bullet’ theory of the 1963 John F. Kennedy assassination are exceptions to this.

Abraham Zapruder’s cine film of the shooting shows the us president and Texas governor John Connally reacting to being hit less than a second apart. The committee charged with investigating the killing – the controversial Warren commission – claimed that only three shots were fired, from a single vantage. The first missed altogether and the second fatally struck Kennedy’s head. This left a third bullet responsible for seven entry / exit wounds across the two men. Having come to rest in Connally’s left thigh, this bullet later obligingly plopped out in near-perfect condition in a hospital corridor.

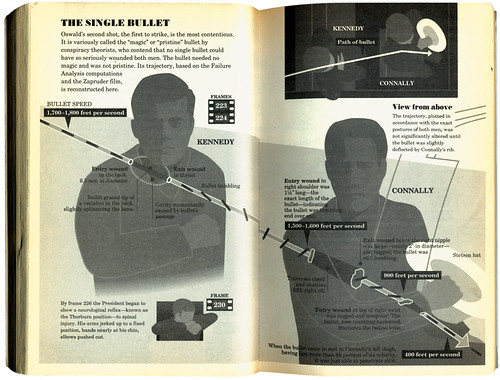

Below: ‘single bullet’ diagram by John Grimwade, published in Gerald Posner’s Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK (Random House, 1993).

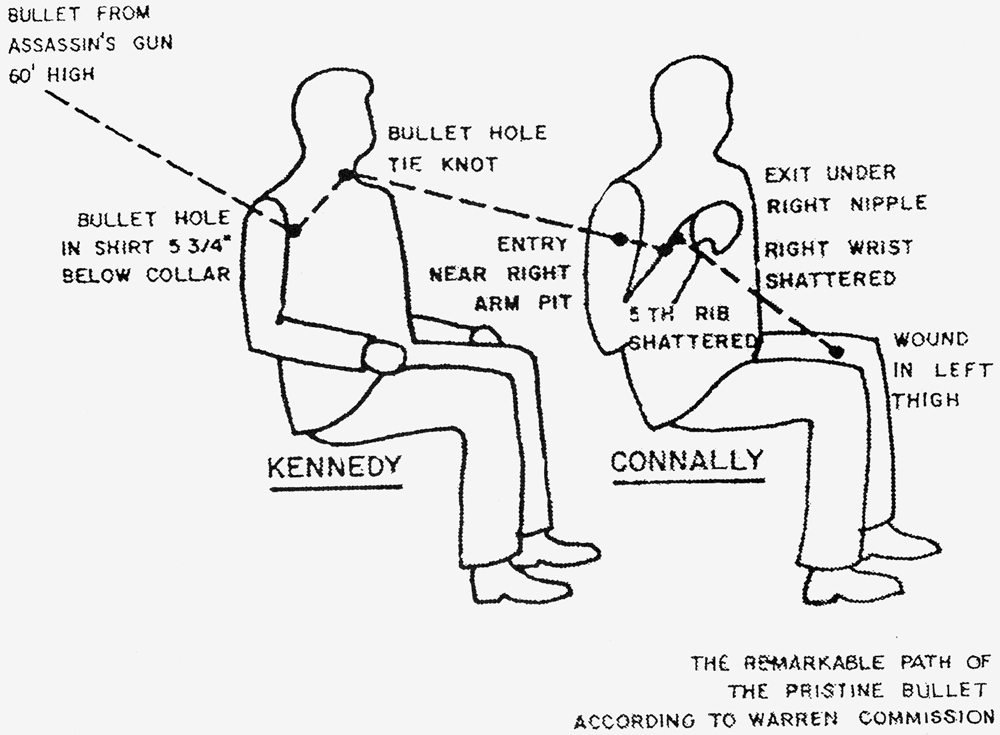

Top: ‘magic bullet’ diagram, uncredited (1967). This version was later reproduced in Robert J Groden’s The Killing of a President (Viking Penguin, 1993).

Data for depicting the bullet’s path might be expected to include at least: A, presumed location of assassin; B, location of victim; C, distance and correlation between A and B; and D, direction of bullet.

The uncredited ‘magic bullet’ diagram, which originates from the investigations of New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison, shows only the most rudimentary aspect of d: Kennedy first, then Connally.

In the version shown here, the two men are left floating, minus even the Lincoln limousine that carried them. The counting of entry / exit wounds is also fumbled, with one dot showing the contact with Connally’s wrist instead of two.

Bluntly, the diagram is limited to refutation: a single bullet cannot travel like this.

There are versions of the diagram that support the Warren commission’s ‘lone gunman’ theory. Gerald Posner’s 1993 book Case Closed includes an example of the bullet’s path in straightened form. The graphic, by John Grimwade, mixes the scientific with the illustrative. The car is as vaporous as in the ‘magic bullet’ version but otherwise more detail is given, down to the shapes of wounds and the bullet’s speed and orientation at each juncture.

Such details jar with the absence of measurement between the two men, the fadeout of Kennedy’s body and the fact that he appears not to have a neck. (This matters. The Warren commission’s draft report said that a bullet ‘entered his back at a point slightly above the shoulder and to the right of the spine’. By the time of publication this had changed to ‘entered the base of the back of his neck slightly to the right of the spine.’) Unlike the earlier diagram, the point of impact with Connally’s thigh is omitted.

In strict information design terms, the conspiracy theorists’ ‘magic bullet’ diagram is severely flawed. But its very vagueness perfectly illustrates that a murder committed in broad daylight, in full view of hundreds of spectators, many cameras and an audio recording could remain subject to so much heated debate, with the real truth unlikely ever to be known.

Christopher Wilson is a graphic designer and writer at Oberphones, Sheffield.

First published in Eye no. 78 vol. 20.