Wednesday, 4:59pm

24 July 2013

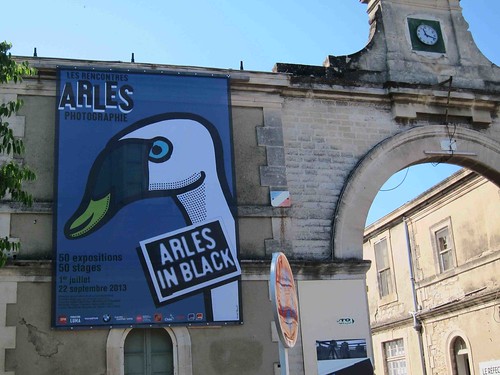

Empathy and doubt in Arles

From the cool alienation of colour to the directness of black and white – Rick Poynor reflects on the 2013 Rencontres d’Arles photography festival. Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

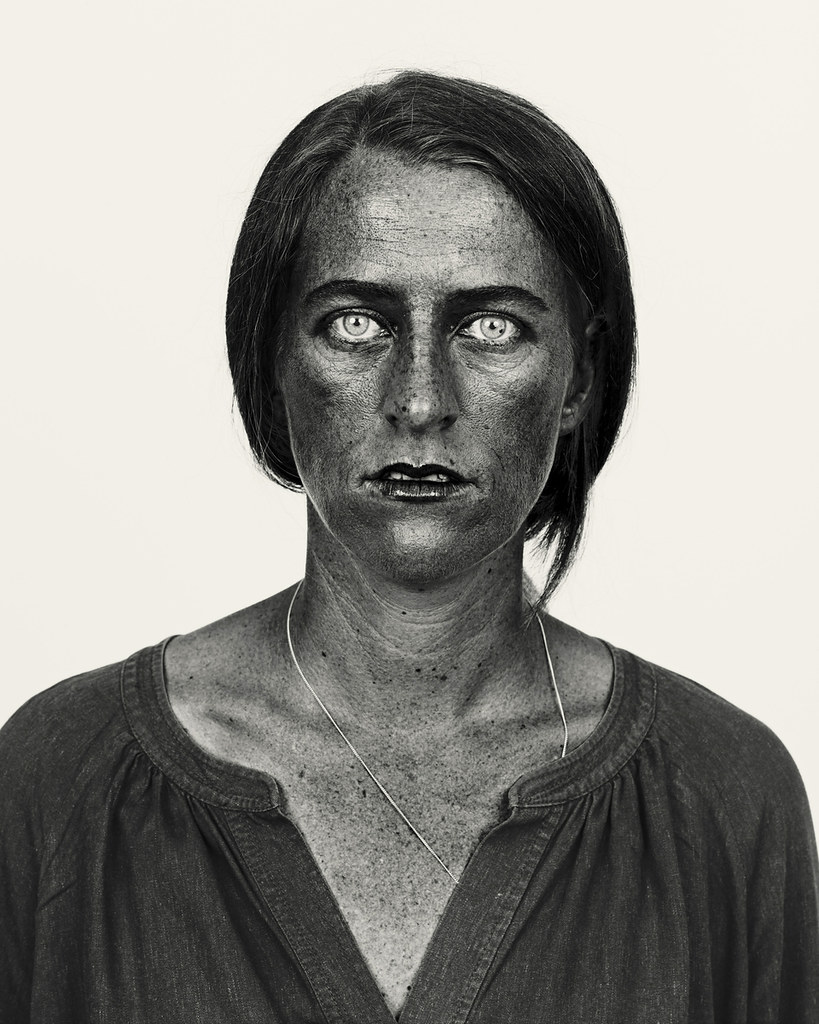

At this year’s Rencontres d’Arles photography festival, Erik Kessels’ 24 Hrs of Photos, first seen at Foam in Amsterdam, gets another airing. A shiny avalanche of pictures sourced and printed from the Internet cascades down a wall and surges across the floor.

There could be no better demonstration of our unslakable lust to take pictures and no more pressing challenge for photographers still committed to the medium as a serious mode of expression. Does the cascade signify an image culture readier than ever to embrace the language and possibilities of photography, or is it a kind of suffocation, the medium’s living death?

Erik Kessels, 24 Hrs of Photos, Palais de l’Archevêché, Arles. Photograph: Rick Poynor.

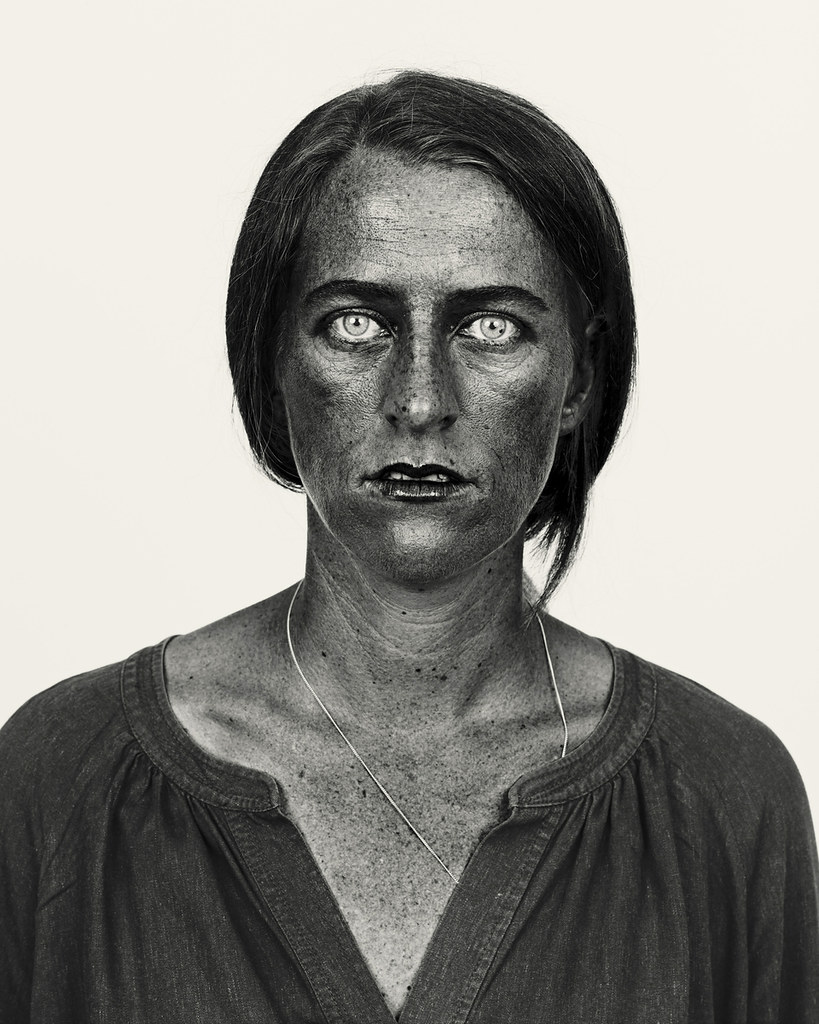

Top: Pieter Hugo, Annebelle Schreuders (1), 2012.

The festival’s main theme can be seen as a riposte to the avalanche: the focus is on black-and-white, a format that seemed to have been definitively trounced by colour. Snapshots tended to be in colour from the 1960s and Kessels’ lava of recent digital snaps is naturally polychromatic. Colour is now also first choice for art photography and for reportage, since the advent of colour printing in newspapers. Popular taste has come to associate monochromatic imagery with the pre-digital past. We have reached the point where continuing to use black-and-white, or reverting to it, can register as a deliberate, fastidious and even exotic choice; it also risks appearing nostalgic for a bygone photo-culture, or as an act of retro style.

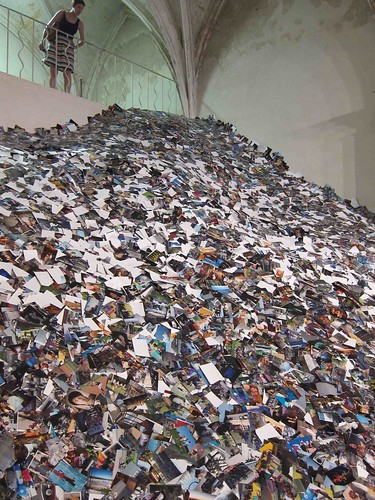

Jean-Louis Courtinat, Alzheimer’s Patient in Her Room, Villejuif, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

There is plenty of compelling black-and-white photography in the festival, but not much sign that a revival is happening or likely since the best displays, in the 50 exhibitions, tend to be bodies of work from the days when colourlessness was the norm. The standouts include the Chilean photographer Sergio Larrain, who gave up taking photographs in 1970 for a life of monastic seclusion. His pictures of everyday struggle and recreation in Santiago and Valparaiso are full of warmth and compassion yet poetically oblique in a way that sometimes seems to prefigure the new wave cinema of the 1960s. He came to London in 1958 and found images of life in the capital unlike any that I’ve seen from that era, capturing the postwar mood of tightness, despondency and limited horizons – in the street, the Underground and the park – with an almost redemptive lyricism.

Sergio Larrain, Main Street in Corleone, Sicily, 1959. © Sergio Larrain / Magnum Photos.

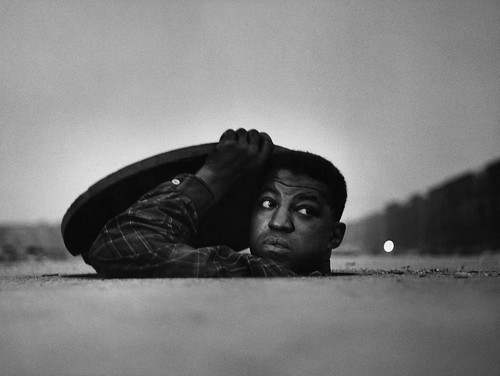

Gordon Parks, Invisible Man, Harlem, New York, 1952. © Gordon Parks Foundation.

Work by Larrain and Gordon Parks – subject of another excellent career survey – reminds us how black-and-white came to be associated with a humanistic perspective later regarded as problematic by theorists of photography. Mid-twentieth century B&W intensifies the human drama of pictures through the control of lighting, while casting a unifying aesthetic continuity, both within the picture and between pictures, over every scene it presents. Realistic colour without modulation is potentially more disjunctive and often, paradoxically, colder in effect. Black-and-white photographers saw the medium as a tool for uncovering and understanding the world and their visual vocabulary became indelibly associated with that idealistic intention.

Pierre Jamet’s delightful pictures of French youth hostellers in the late 1930s – one of the festival’s surprise hits – express a joie de vivre in simple outdoor activities (hiking, cycling, taking a hosepipe shower, peeling potatoes) that is hugely touching, partly because we know that the idyll will soon end with the coming of war.

Pierre Jamet, Dina Naked and Splashed, Villeneuve-sur-Auvers Youth Hostel, 1937.

The largest exhibition, occupying seven rooms in the Parc des Ateliers, is given to Wolfgang Tillmans who shows inkjet prints, easily the biggest pictures in town, hanging casually from clips. Bucking the festival’s theme, they glow with superheated colour. Tillmans has always seemed overrated to me and I went to his show twice in hope of discovering what I was missing.

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans’ ‘Neue Welt’ (New World) exhibition.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Headlight (b), 2012. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne.

Where photographers such as Larrain and Parks betray every sign of engagement with the people they photograph, Tillmans offers banal, snapshot-style street scenes culled from his restless global travels. They feel under-composed; their impact comes mainly from their inflated size. As with previous shows, Tillmans mixes diverse subjects to prompt associations. His interest in lifeless, artificial surfaces is most telling in pictures of car headlights, train carriages, hotel rooms, marine equipment and food in repellently intimate close-up. There is more vitality in a single black-and-white shot by Larrain of a little girl on a Sicilian street in 1959, but that might be the point. Colour is much better for postmodern detachment and alienation.

Discovery Award nominee Clare Strand, Skirts, 2012. Courtesy of Clare Strand and Brancolini Grimaldi.

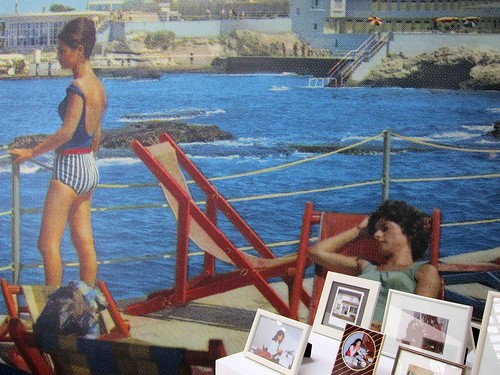

Installation view of Discovery Award winners Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh and Rozenn Quéré’s Possible and Imaginary Lives, 2012.

I was less impressed than on previous occasions by work featured in the festival’s Discovery Award and this was where the case for the continuing relevance of black-and-white most needed to be made. The winners, Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh and Rozenn Quéré, blend fact and fiction in their installation, a mixture of colour and B&W found photos, about the lives of four Lebanese-Palestinian sisters. They share a taste for old family photos with Kessels, while proving that at this point more needs to be done with the material than simply showing off other people’s discarded pictures, as Kessels does in his ‘Album Beauty’ installation. Other nominees investigate antiquated pre-colour processes such as waxed paper negatives, the wet plate collodian / tintype process and the camera obscura with diverting results, though none of this feels especially urgent.

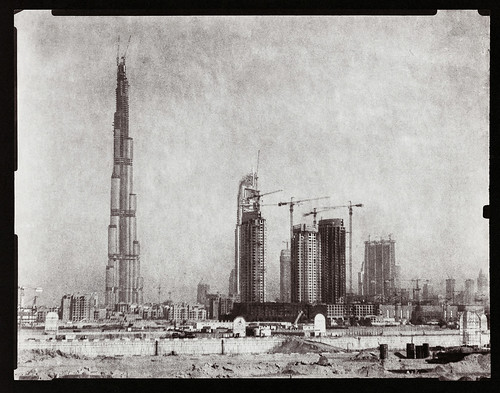

Discovery Award nominee Martin Becka, Burj Al Arab, 2008, from the ‘Dubai Transmutations’ series. Salt contact gold toned print from a waxed paper negative (Le Grayâs process).

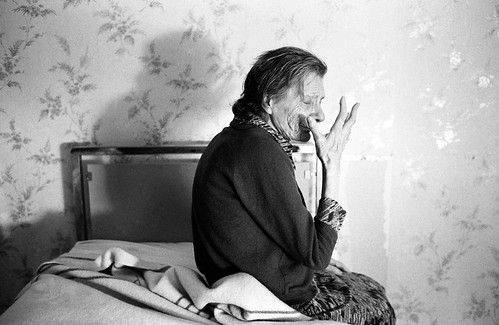

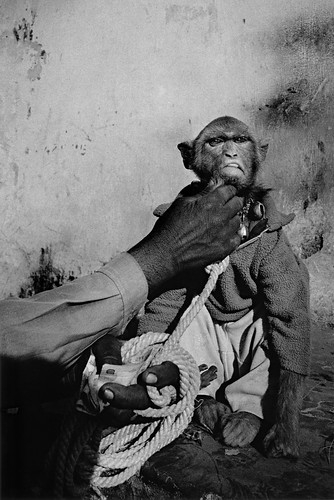

There is always far too much at Rencontres to do most of it justice in a review. The great pleasure of making your way slowly around several dozen exhibitions lies in the potential for unexpected discoveries. This year, one of the most memorable, for me, was the work of a Belgian photographer I had never encountered before, Michel Vanden Eeckhoudt, who has used black-and-white since the 1970s. His startling images of dogs, pigs and primates appear to reveal these often solitary creatures in a state of what I can only call existential anxiety and unease. Or maybe this is merely a clever photographic trick that encourages the viewer to project states of awareness on to the animal that it cannot possibly be experiencing as a non-thinking, non-conscious being. We have no way of knowing conclusively, but by these acts of identification with his non-human subjects, Vanden Eeckhoudt creates spaces for empathy, speculation and doubt.

Michel Vanden Eeckhoudt, India, 2008. © Michel Vanden Eeckhoudt / Agence VU’.

The Rencontres d’Arles photography festival continues in Arles, France until 22 September 2013.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.