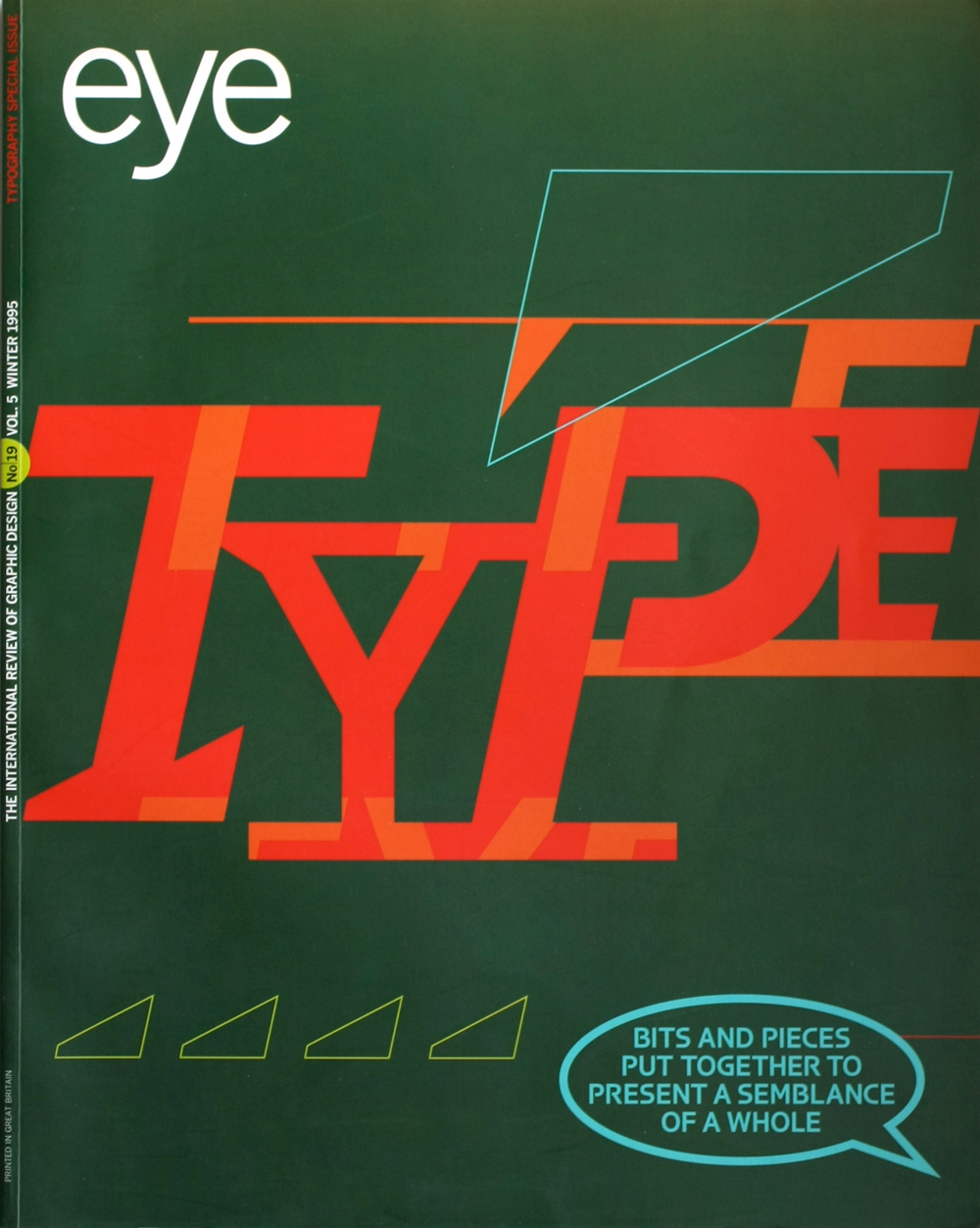

Winter 1995

Mysterious absence at the cutting edge

Marlene McCarty

Mary Lewis

Siobhan Keaney

April Greiman

Paula Scher

Deborah Sussman

Ellen Lupton

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

Katherine McCoy

Lorraine Wild

WD+RU

Teal Triggs

Siân Cook

Zuzana Licko

Valerie Wickes

Critical path

Design education

Graphic design

Britain has many design stars and most of them are men. Yet very few young women want to be seen as feminists. That’s starting to change

Despite the fact that more British women now work in graphic design than ever before, there are still precious few female faces in the upper echelons of the profession.

The leaders in the limelight, those invited to speak at conferences, talk to the press and appear on television representing the industry to the public, are almost invariably male. With a few notable exceptions (this year’s D&AD president is Lewis Moberly principal Mary Lewis), women seem to be either reluctant to draw attention to themselves, or resigned to playing second fiddle as assistant or associate to a male chief.

Nor is it any better at graphic design’s more youthful cutting edge. If anything, it’s worse. With the demise in the 1990s of the caring, sharing, baby-holding new man as a popular image, an alternative media construct – the crop-haired new lad devoted to football, beer and babes – has been adopted as a model by young male designers en masse. This tightly knit, London-based gang gets a disproportionate share of attention in the pages of the trade press and thus shapes wider perceptions of what the industry is about. There is, as yet, no all-female equivalent to the atelier of male superstar experimentalists cutting a rebellious swathe through advertising, typography and design. Young women contemplating a career in these testosterone-fuelled precincts need to be made of pretty stern stuff.

But mention the word ‘feminism’ to a female designer in the same age bracket as the young guns – 25 to 35 – and the chances are that she will be reluctant to nail her colours to the mast. After 30 years of feminist-bashing by the British press this may not be such a surprise; it’s an attitude shared by young women in all walks of life. According to Royal College of Art student Susen Vural, who recently completed a thesis on ‘the mysterious absence of women at the cutting edge of British graphic design’, both men and women students would rather not address the issue. ‘The term feminism is ridiculed,’ says Vural. ‘They think it’s funny that I’m bothered. They don’t think we still need to redress the imbalance. You have to be personally courageous to call yourself a feminist.’

RCA tutor Siobhan Keaney [now at University of Brighton] is one of the few female designers to have achieved a relatively high level of recognition in her own right. ‘The real lad element is very strong in graphic design,’ she agrees. ‘The gang mentality means they all hang out together with the young creative teams from ad agencies, helping each other.’ But Keaney sees encouraging signs among the new generation of students that this may finally have reached a head. ‘Students are recognising the closed shop attitude and addressing the issue of sexism because they want to know they can become part of the profession.’

Britain has a long way to go, though, before we achieve anything comparable to the situation in the US, where the larger percentage of women working outside the home in the post-war years has meant that emancipation was never perceived by the male workforce as such a threat as it was in Europe. The high-profile, well-respected women working within the American graphic design community have never felt the need to deny the struggle for equality. Designers such as Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Katherine McCoy and Lorraine Wild have consistently addressed sexual politics in their design work, writing and the study programmes they have established at some of the country’s most prestigious design institutions.

Teal Triggs, course leader in graphic design at Ravensbourne College of Design and Communication [now at the RCA], and herself an American, believes that the more radical attitudes of the American design community are also the result of a less rigid educational system. In the US, design students are not confined to an art college ghetto, but can take courses in disciplines which promote political awareness, such as the humanities and social sciences, along with design, fine art and photography. The hard core of practitioners across generations and genders who consistently address political issues in their work and writing has engendered a climate which has helped to establish the profile of such women as April Greiman, Paula Scher, Deborah Sussman and Ellen Lupton.

In the UK, where young people specialise as early as sixteen, the interrelationship of social issues and design tends to remain the province of postgraduate institutions such as the Royal College of Art, whose current first year, significantly, contains eighteen female and only six male students. At undergraduate level it is sometimes a different story. In an effort to overturn their male:female student ratio of 7:3, lecturers on the Btec HND Design course at Newham College of Further Education in east London have addressed the issue of inequality through the syllabus, with significant results. ‘We encourage problem-solving,’ says lecturer Sue Roscow, ‘and we wanted to solve the problem of having too few women students.’ Strategies include publishing a statement of intent in the prospectus, setting research-based projects on writers such as Germaine Greer and Betty Friedan and using role play to prepare students for potentially difficult interview scenarios. The new course attracted many applicants, with roughly equal numbers of men and women.

New technology has also had a liberating effect on women entering the industry. As a design tool, the computer is less overbearingly male-identified than traditional printing and typesetting, while the choice of workplace and self-sufficiency it brings have obvious advantages for women. Affordable technology enabled Zuzana Licko of Emigre to operate on her own terms in an environment she could control. ‘I didn’t like having to sell my design,’ she recalls. ‘I felt uncomfortable walking into a room of clients, 40-year-old guys in three-piece suits. I couldn’t smoke a cigar with them. That’s what brought me to switch to type design and to work for myself.’

The issue of women and new technology, and in particular multimedia, is central to the concerns of the Women’s Design Research Unit (WD+RU), set up in January 1995 by Teal Triggs and Graphic Agitation author Liz McQuiston to raise awareness, disseminate information and instigate design projects. WD+RU member Karen Mahony, an interface designer with her own company, Mahony King, recognises the opportunity multimedia provides to rewrite the male-authored rulebook. ‘I don’t want the stereotype of a multimedia designer to replicate the laddish graphics star,’ she says. ‘There are hardly any women doing computer-based BAs and the numbers are falling. We have to show that women can work with technology, so as to encourage a balance.’

WD+RU are convinced of the empowering effects of computers, and not just within the design world. They aim to talk to women in all walks of life, but the first step is to initiate a debate that will politicise designers and prompt them to address gender issues through their work. WD+RU’s first project was Pussy Galore, a typeface published by Fuse, satisfyingly enough, as it was the lack of women speakers at the first Fuse conference that member Siân Cook cites as ‘the last straw – we had to do something.’

Can feminism be made relevant to the current generation of designers? Certainly the strict theoretical doctrines that found favour in the 1970s have lost their appeal in the world of the 30-second soundbite, along with feminists’ dungaree-clad, separatist image. But if we reconsider feminism not as an ideology that can go in and out of fashion, but as a dynamic strategy for producing change and allowing a multitude of voices and attitudes to co-exist, it could once again achieve contemporary significance. ‘A fundamental belief in feminism fuelled all our discussions,’ says Marlene McCarthy of Bureau in New York. ‘We’re designing posters for the United Nations Population Fund, a mind-expanding project concerning women’s issues in developing countries. The idea is that if women can empower themselves, the quality of life for everyone in their community will change for the better.’

Valerie Wickes, head of graphic design at Din Associates, a multi-disciplinary design consultancy specialising in fashion, and chairwoman of the professional networking group Women in Marketing and Design, highlights the problems of introducing a feminist perspective to mass-market clients. ‘A lot of the images I make are of glossy, unobtainable, thin women and I do see the wider implications,’ she says. ‘We try to push images of stronger women, but in the end the client can say no.’ But it cuts both ways. If she thinks a client is totally misguided she is prepared to make herself heard. ‘I did walk out on one client, the clothing division of the supermarket chain Asda, who insisted that every female model wore a wedding ring to signify respectability. I kept leaving it off.’

Every profession should mirror the society it serves. Meeting the communication needs of a multi-cultural, multi-racial, gendered audience is impossible if the only reference points are those of a white, middle-class male. Within graphic design a few basic strategies could radically improve working practices and the status of the profession, to everyone’s benefit. First, accept there is a problem – then take action. Overturn the profession’s boys-only image; recruit more women students into graphic design education; raise the profile of those women already working as designers; and exploit working practices which empower the individual. Use the power of graphic communication to tackle all of these issues.

Siân Cook of WD+RU points to the changes that have taken place in the 1990s in rock music, where women enjoy a more assertive presence than ever before. ‘Graphic design is about five years behind pop music,’ she says. ‘Wait for this generation of students to graduate and we’ll start to see what the new all-girl bands can do.’

Liz Farrelly, design writer, London

First published in Eye no. 19 vol. 5, 1995

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.