Spring 2006

Ware comes back with a darker narrative

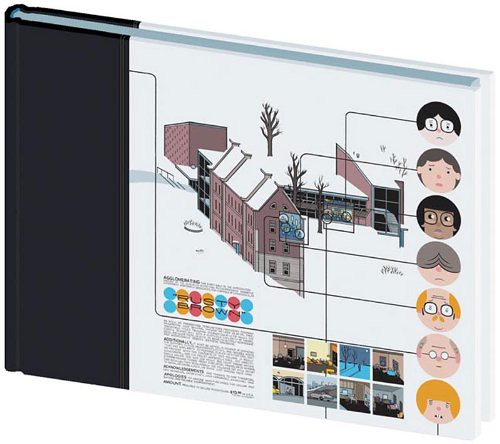

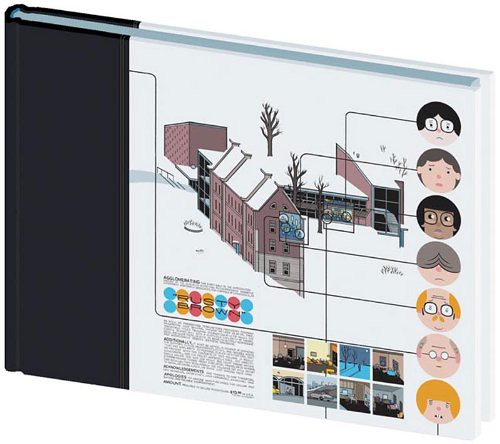

The Acme Novelty Library #16

By Chris Ware <br>Fantagraphics, USD 15.95

After a four-year hiatus spent repackaging earlier work for a mainstream audience, Chris Ware finally resumes his acclaimed Acme comic series with new material in a handsome volume limited to 20,000 copies. Ware’s sense of tragicomic absurdity is undiminished, and a renewed focus on extended narrative is in evidence. Recent offerings, such as the Acme compendium published by Jonathan Cape, relied heavily on a repetitive short strip format that undermines emotional engagement. (Ware once summarised his handiwork as ‘outrageously complex pages which often do no more than deliver a single morbid gag as payoff’, and to some extent this is true, at least for recent compilations.) Here, however, Ware returns to character and narrative development, with stories that will unfold over years – a move which heightens his depictions of farce and disappointment.

Just as the Jimmy Corrigan graphic novel was distilled from seven years of Acme, this latest instalment serves to launch two new strips, both of which are ultimately to be published in graphic novel form. Building Stories (which also appears in the New York Times Magazine) involves the domestic adventures of the various inhabitants of a brownstone apartment block. Imagine a comic book version of Hitchcock’s Rear Window, but with elaborate causal diagrams and fastidious schematics.

However, the main attraction is Rusty Brown, a darker and more squalid foil to Jimmy Corrigan. Short scenes of Rusty’s later life have appeared in previous issues, hinting at things to come. We have already seen a middle-aged Rusty squatting in soiled underpants beside the door of an occupied bathroom, attempting to pass a broken toy to the girl inside and oblivious to the consternation of the girl and her parents. Where Jimmy was benign, socially paralysed and largely asexual, Rusty is dishonest and queasily fetishistic. Both characters are emotionally arrested and socially inept, but a new sexual undertone gives Rusty Brown a genuinely disturbing edge. Rusty’s story begins at the age of eight with a winter’s morning at school, a new classmate, Chalky White, and an unsavoury attachment to a superhero doll. (‘Don’t fly away, Supergirl. Your costume is being blown down by the wind. Let me …’) By the end of the first instalment – just a few minutes later – the cast, including Ware himself, has been introduced and Rusty’s fixation with Supergirl has grown to alarming proportions.

A key visual device employed throughout the book is the depiction of multiple perspectives. The top three quarters of each page show the various interactions of the principle characters, up to and including the arrival of Chalky White. Running parallel to this at the foot of each page, we follow Chalky’s point of view, and those of his family, synchronised with the main narrative. These two narrative threads gradually interact and counterpoint each other to ingenious effect. Quizzed on his chosen medium, Ware described comics as a form in which ‘the human experience of time can be most beautifully represented on a page.’ In this he is correct, and is among its finest exponents.

David Thompson, writer, Sheffield

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.