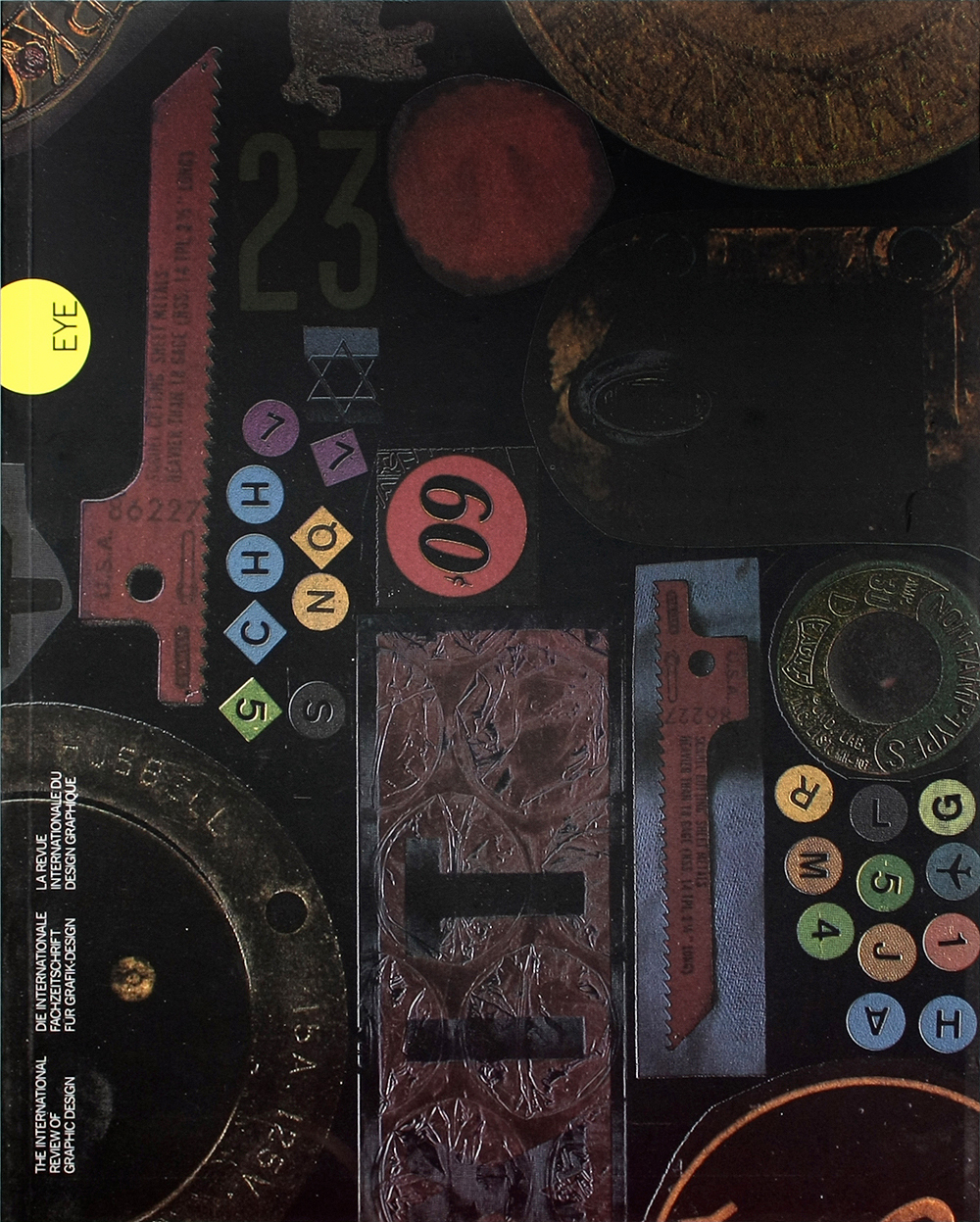

Winter 1990

When an ad becomes art

Art & Publicité 1890-1990

Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Spring 1991Admen have long yearned to be taken seriously as artists. Visual artists have long helped to serve advertisers’ sales pitches. The exhibition ‘Art & Publicité’ at the Pompidou Centre in Paris examines a century of inspiration and influences shared between the two disciplines. Ambitious and encyclopaedic, with curatorial contributions from the art, design and film departments, the exhibition strives to demonstrate that art has shaped the look and tone of advertising as much as advertising has influenced the form and content of so-called ‘fine art’.

One of the exhibition’s themes is that a well-designed advertisement is an artistic statement in its own right . Supporting this assertion are print campaigns from the 1950s for Container Corporation of America, Paul Rand’s logo treatments for IBM and Giovanni Pintori’s ads for Olivetti. Yet if anything, ‘Art & Publicité’ unintentionally supports the idea that the admakers’ inevitable sales pitch separates “real” artists from well-dressed hucksters. The exhibition certainly acknowledges the creativity of designers and agencies such as Doyle Dane Bernbach for its classic Volkswagen Beetle television ads in the US. But whereas the ad work of artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec or Alphonse Mucha survive as art, ads here live on simply as ads.

Perhaps because the curators assumed that Pop Art has been thoroughly explored elsewhere, it is passed over quickly. This is regrettable, since Pop was a break-through in the synthesis of art and advertising. The 1960s movement also informed the work of 1980s artists such as Jeff Koons and Haim Steinbach. But rather than exploring these links, the show concludes with a slapdash sampling of work of the 1970s and 1980s from Hans Haacke, Jacques de la Villeglé, Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Jenny Holzer and others.

Much of this work, is self-referential and possesses little resonance. Koons’s stacked Hoovers in their dust-free, clear acrylic boxes are chillingly elegant displays of art as product; in Holzer’s digital signbox, messages self-consciously aware of their medium race by with an echo of the here-now, gone-tomorrow planned obsolescence that advertising helped to create.

Former magazine designer Barbara Kruger, like the Pop artists, takes on both the art world and the world of popular culture by employing mass-media techniques to make and present works of art. Her emblematic, photomontaged tableau from 1987 with “I shop therefore I am” emblazoned across an anonymous outstretched hand says more about consumerism than much of the rest of the show taken together. The crisp message and streamlined graphic could come straight from a primer on simple and effective advertising strategies.

Exhaustive and exhausting, “Art & Publicité” could have benefited from a more focused selection of work. Classics such as Toulouse-Lautrec’s Moulin Rouge posters, Picasso and Braque’s Cubist collages incorporating cigarette wrappers, the Constructivist posters and Bauhaus typography alone make the show worth seeing: it is hard to imagine so much primary material of this kind being assembled again. But there is no need for a roomful of de la Villeglé’s and Raymond Hains’s ripped-from-the-wall fragments of street posters, for instance.

More striking are some of the Futurist and Dadaist graphics, though their sound and fury, inspired by the mass-media techniques of their time, seem muted, more than half a century later. The bold graphics of Futurist Fortunato Depero – for example, the monkey figure drinking with a straw for Campari – personified consumption all the better to encourage it.

Jean-Hubert Martin, the former director of France’s National Museum of Modern Art in the Pompidou Centre, explains that the show was undertaken because “in order to understand the evolution of twentieth-century art, it is necessary to consider the context in which it has been made.” Providing more content than conclusion, this survey breaks little ground in a subject area that has already well examined. Although the show’s beginning is more interesting than its end, the later sections do suggest that, like it or not, the strong link between art and advertising is bound to endure. But the exhibition, like a well-stocked supermarket offering many choices, leaves the decision of what to make of this relationship up to the consumer.

First published in Eye no. 2 vol. 1, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.